Jul 13, 2020

The Hagia Sophia is making the news these days because the Turkish president is changing the status of the great building from a world museum and UNESCO World Heritage site…to a mosque. But what is the Hagia Sophia? It’s perhaps a shame that so few understand the incredible role the Hagia Sophia basilica played in world history.

The medieval era marks one of only four major eras in human history. Historians generally classify the medieval era as lasting from 500 to 1500 C.E. Well, the Hagia Sophia fulfilled its historical role from 537 to 1453 – the exact time frame of the medieval era. Perhaps no other building exists in the Western Hemisphere that serves as a better embodiment of the medieval era than the Hagia Sophia.

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

Many people in the world today view the St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City as the center of Christendom. And yet, St. Peter’s Basilica is a scant 394 years old. By comparison, Hagia Sophia is 1,483 years old. Go ahead a whistle if you’re impressed. Unlike many buildings of this vintage, the Church of Holy Wisdom, as it is alternatively called, is still fully functional.

Older than Islam, the Hagia Sophia basilica had been built as the monumental symbol of Christendom on earth. The bulky structure faces out to the world with a hue of faded red paint, crowned by a purple-gray dome, and topped with a golden spike. Four minarets flank the building, two at the fore and two at the rear (these are more recent additions).

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

Timeline of the Hagia Sophia:

532 – The original Hagia Sophia was destroyed during the Nika Riots

537 – The current architectural wonder is completed during the reign of Justinian and Theodora the Great

1204 – Converted to a Roman Catholic cathedral, after Western crusaders sack Constantinople

1261 – Returned to the Eastern Orthodox Church

1453 – Converted to a mosque after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks

1507 – Construction of St. Peter’s Basilica begins in Italy to replace the Hagia Sophia

1616 – The Blue Mosque is built across from the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul

1626 – St. Peter’s Basilica is finally consecrated

1934 – Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the father of modern Turkey, converts the Hagia Sophia to a museum

2020 – President Recep Ergodan, Turkey’s current leader, decreed the Hagia Sophia to be a mosque again

While Europe was slogging through a violent and regressive dark age, the Hagia Sophia rose above the city of Constantinople as a bulwark of civilization and a beacon of religious devotion that defined the era. The Hagia Sophia was the largest church in the world, with one of the largest enclosed spaces until modern times, and featuring architectural distinctions that redefined architecture.

I’ve been there. I’ve seen it. And the building is spellbinding. After passing through massive doorways once reserved for Roman emperors, you enter a cavernous space of gleaming marble, a forest of marble pillars, and a haze of foggy sunlight peeking through the windows. One gazes up into the underside of the great dome and falls dizzy with wonder.

In my opinion, the Western world doesn’t give enough credit to the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire that built the Hagia Sophia. Clearly, we took for granted that such an important site wouldn’t be nationalized at the snap of one man’s fingers. And since human depictions are not allowed within mosques, the stunning historical mosaics that adorn the walls will likely be covered up with plaster or some other means. This is equivalent to covering up the ceilings of the Sistine Chapel.

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

The Hagia Sophia should remain a museum. A museum is a higher calling since it preserves something about all human history, regardless of religion or nation or politics. It’s universal and inclusive. A museum belongs to all of us and enlightens us. If you suspect that perhaps you don’t know much about the Byzantine Empire, please explore. It’s fascinating. The Byzantines set the table for the modern world in ways you may not have suspected.

History matters. And we must never forget.

Douglas A. Burton is an author of historical fiction. His critically-acclaimed and award-winning novel, ’Far Away Bird’ follows the early life of Byzantine Empress Theodora. Doug has been on a mission to introduce the Byzantine Empire’s vital role in history and Empress Theodora’s vital contribution to women’s rights.

Further reading:

Empress Theodora: Origins of Women’s Rights

History’s Greatest Cover-up: The Byzantines

Jan 23, 2020

Here’s a fun little test. Name a major mainstream movie, television show, or novel that has the Byzantine Empire as a setting and from the Byzantine perspective. No, really, name one.

I mean, we have movies set in ancient Greece, Ancient Egypt, Rome, Medieval Japan, Medieval China, South America, the Mayan Empire, Antarctica, Mars, Middle-Earth, and Tatooine. And yet, the vast and exotic Byzantine Empire seems to be “redacted.” Seriously. Why?

Most of our perception of Byzantine culture comes indirectly through our fascination with the mysticism of Eastern Europe. We see it in stories like Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which takes place in Romanian Transylvania and has an occultic Byzantine feel, or Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express. We see the Hagia Sophia in movies like From Russia with Love, The International¸ or Tom Hank’s Inferno. And most recently, Millennials walked on the streets of 16th Century Constantinople in the critically acclaimed video game, Assassin’s Creed: Revelations. But these are just scant traces of Byzantium in our modern culture.

(Above) Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992). (Below) Assassin’s Creed: Revelations (2011)

For 25 years, I’ve read about the Byzantine Empire and only a few of my closest friends and family members know about my unusual side passion. Even they don’t ask “why” anymore. Whenever I do end up mentioning something about the Byzantine Empire, or that the capital was Constantinople, the most common response I get (and I’m not kidding) is a pause and then a cheery rendition of Istanbul Not Constantinople. So now it’s Istanbul, not Constantinople, and we all get that.

But how did this particular time and place in the world come to capture my imagination so entirely? Like many things for me, the culprit was a book.

I can actually tell you the exact day my fascination with the Byzantine Empire began. It was in March of 1993. I know this because the library card is still inside the book cover to this day. The book was a non-fiction work called Constantinople: Birth of an Empire by Harold Lamb, and it was published way back in 1957. During my 1993 study hall, though, I just needed a book to pass the time because I surely wasn’t going to do my Algebra homework. So, I flipped through the pages, and the musty scent of old paper really set the tone. There were some black & white pictures on a few pages depicting a mosque-like building of some kind, various mosaics, and stone reliefs. I turned back to the first page and started reading…

The author opens with:

This is the story of a city built by survivors. As often happens in a great disaster, these survivors were not one people ethnically, but a fusion of many peoples. They gathered together to defend not so much their lives and property as their way of life. In so doing, they displayed a certain perversity; they refused to surrender their city. They kept on refusing for nearly a thousand years. History has named them the Byzantines…

So, wait a minute, I thought. This sounds nothing like the Roman Empire I learned about in any schoolroom. The Romans were of one people ethnically, you know…the Romans? So, this account baffled me. The Roman Empire was a civilization built by brute conquerors, not desperate survivors.

The author goes on:

They were alone in their survival. In the West, a long twilight fell on the Roman Empire during the centuries between A.D. 200 and 450. It ended in the darkness of the first Middle Age. In the East, however, the inhabitants of this city learned the hard lessons of disaster, and they managed to hold back the night.

Images of invincible Roman legionnaires, of architectural splendor, and ancient decadence all seemed at odds with the rather morbid tone the book struck. What the hell was this guy talking about? I flipped to a map in the index and got a better idea. The Roman Empire had been split in two at some point, a west and an east empire. I remembered hearing something about the split but then also realized that I never heard about what happened to that eastern portion of the empire. It was like the weird old uncle you meet at a family reunion and never hear from again.

Here’s what I’m talking about:

So, apparently, the Roman Empire we all study in school is the green part, the western part, the European part with its iconic boot of Italy kicking Sicily, and with the familiar shapes of France, Spain, and England facing the Atlantic Ocean. But there’s that whole red side, the less European side, the more Middle-Eastern side, which clearly includes Greece, the Balkans, Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Israel, Egypt, and some of Libya. Even today, that red side includes a rare fusion of diverse cultures that actually encompasses three continents—Europe, Asia, and Africa.

The author then launches into a spellbinding account of the late Roman Empire—not in its glory—but in the spasms of a violent death throe. He painted a picture of an absolute catastrophe. I still get goosebumps remembering my first impression of this tale.

Civilization had failed in totality.

Rome was sacked. Pillaging went on uncontested and tiny villages were left to fend for themselves. Barbarians migrated freely through the once secure interior of the empire. Imperial highways fell into disrepair. Stray cows milled about in the ruins of monuments, where nature crept back to reclaim the space. Roman soldiers deserted and joined the enemy. Noble families sailed out to escape their doom, only to be captured and sold into slavery. My seventeen-year-old self beheld a disaster on a scale so great that my imagination filled with epic oil painting-like scenes. And the story kept getting worse.

Thomas Cole’s ‘The Course of Empire’ series

Various people made radical attempts at survival in remote pockets…and failed. Desperate Roman emperors passed equally desperate policies in hopes of staving off the ruin of the empire…and failed. Finally, the black shadow of the Dark Ages truly descended upon a world that had actually lost the ability to function or even exist. I was amazed at such a thorough regression of a flagship human civilization.

In one quick stroke, my study hall that day shattered everything I thought I knew about the Roman Empire, of Western civilization. My belief that history represented steady upward progress fell short. I never considered that we could regress so decisively.

But in the East, on the side of the world we rarely talked about in class, I suddenly discovered that half of the Roman Empire survived. That “red section” had a history of its own, and it deviated quite a bit from the Roman Empire I understood.

The eastern empire was a second, bizarre Roman Empire, divorced from Europe, which didn’t even include the ancestral capital of Rome. The citizens spoke mostly Greek, not Latin. They were Christian, not pagan. They were the former conquered provinces, not the founding homeland. And from the ashes of the fallen western empire, I discovered that this eastern Frankenstein remnant of the Roman Empire would come to be known as the Byzantine Empire. These people and their empire would come to dominate the Medieval Era as the superpower of the world, exploding in culture, influence, and art.

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

The Byzantines had little in common with the Dark Age barbarism and stagnation occurring in Europe. Moreover, the Byzantine Empire would go on ‘surviving’ for over a thousand years, making it one of the longest-lived civilizations ever.

I was so enchanted by the world I found in those pages that I pretended to lose the library book rather than return it. I paid the $18 lost fee and proceeded to horde this book my whole life.

In these pages, I met a beautiful cast of historical figures I’d otherwise never heard of, heroes and heroines who called themselves Roman but wore Asian or Russian-looking gowns and gaudy bejeweled crowns. I discovered a Byzantine general, named Belisarius. He was Justinian’s prime general and is considered a military genius. He’s considered one of the top military minds in all human history. See for yourself. Google ‘top 100 generals of all time.

(http://www.worldhistoria.com/the-top-100-generals-of-history_topic124028.html

Again, to my shock, I learned something that I never heard about in school. Remember that colorful map above, half-green and half-red? Well, Belisarius manages to reconquer the entire green section, single-handedly reuniting the Roman Empire for a generation. Impossible to believe! The civilized world fought back against the barbaric dark age.

I also read about a peasant named Petrus, who left his pig-farming village in modern Macedonia to go on to become arguably the greatest Byzantine Emperor in history. He takes on the name of his adopted father and becomes Justinian.

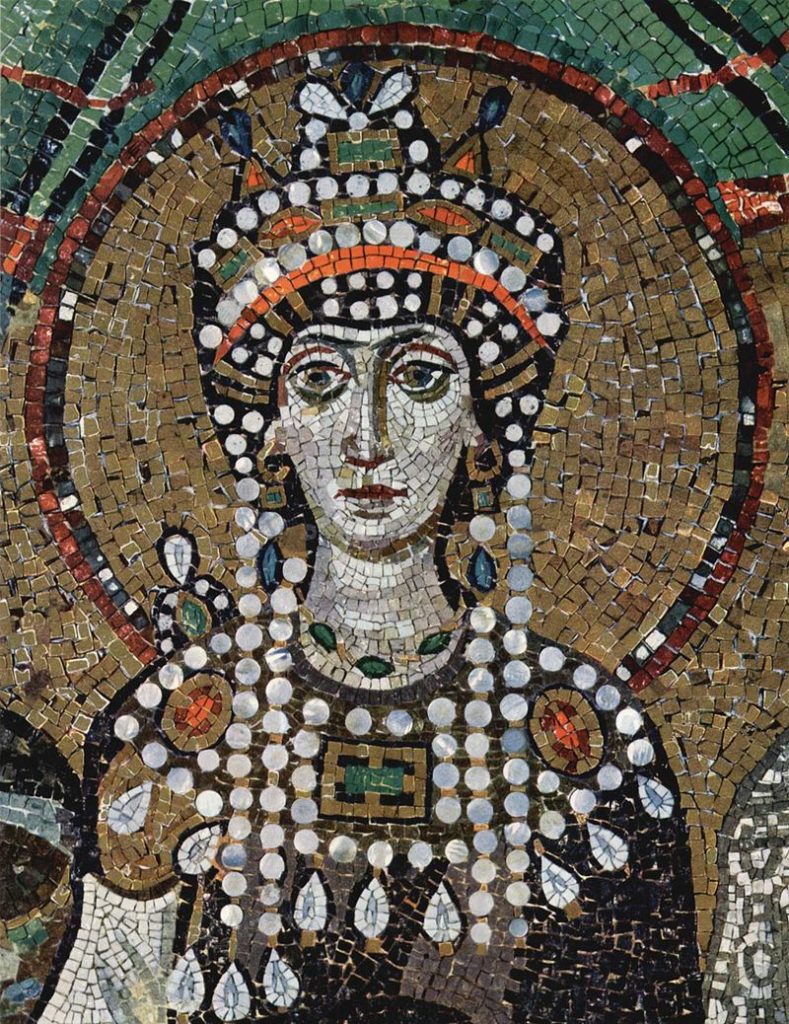

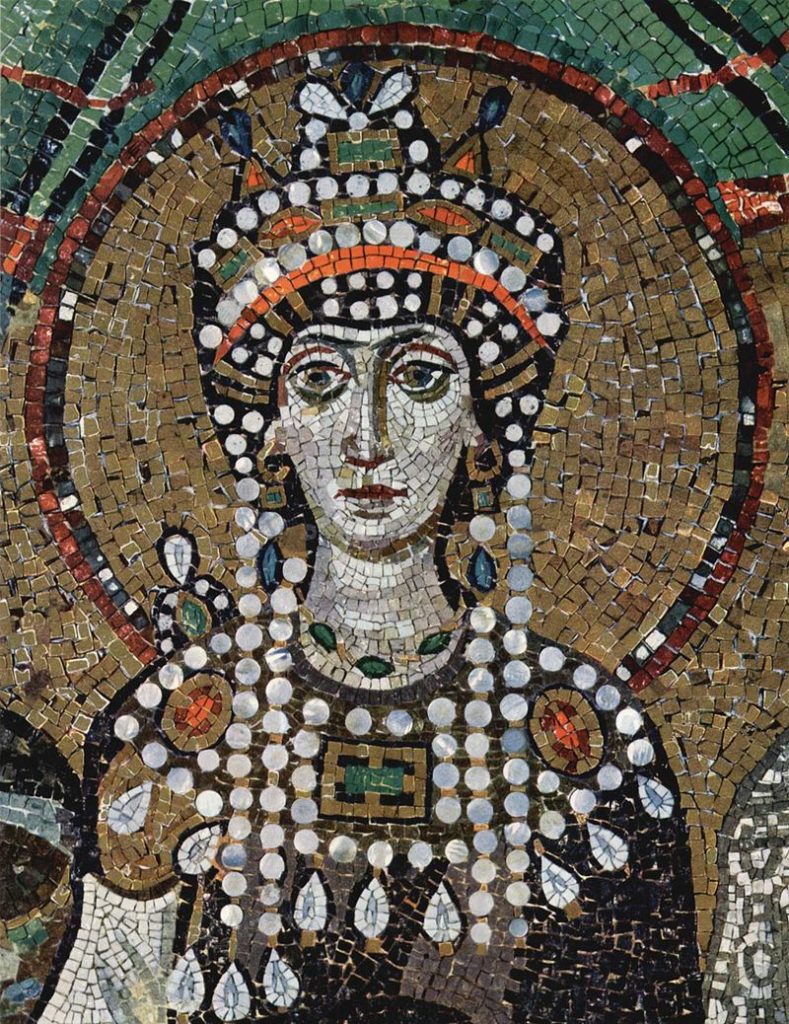

And then there’s his wife, Empress Theodora, whom history has never been more uncomfortable acknowledging. She had been a lowly prostitute, well known for her infamy in the seedy entertainment districts of Constantinople. She was essentially a medieval stripper and sex performer, who goes on to become a powerful intellectual contributor to Byzantine law and culture. Theodora’s undeniable influence on a sweeping legal overhaul represents some of the first Western laws designed specifically for the betterment of women and directed by a woman. The body of laws she influenced, the Corpus Juris Civilis are considered to be among the founding documents of the Westen legal tradition.

Mosaic of Empress Theodora in St. Vitale (Ravenna, Italy)

So, that one book opened me up to all of these aspects. This wasn’t the Dark Ages of Europe. This was a golden age of Byzantium. Sometimes, learning about Byzantine history feels like I’m unearthing a deep historical secret ala The Da Vinci Code or the lost city of Atlantis. And this is made all the more maddening that so few know much about it.

And yet history is incomplete without the Byzantines. For example, I was always told that Western Europe just kind of ‘woke up’ from the Dark Ages. But that’s simply not true. The Italian Renaissance began as the last generation of Byzantines made their way into Europe to escape subjugation. They brought with them their Greek culture, their literacy, legalism, and ideas. It’s well documented that the Renaissance has an unmistakable flair for Greek revivalism and that’s because of the Greek-speaking Byzantines. Within the next few decades, the Protestant Reformation began against the Catholic Church, to whom the Orthodox Byzantines had always been a rival.

Raphael’s Renaissance painting ‘The School of Athens’

Secondly, the Turks captured Constantinople in 1453. This closed the trade routes from Europe to Asia. Did you know that the fall of the Byzantine Empire is the exact event that sent desperate European explorers across the Atlantic to find the New World? This obviously led to the Western discovery of America in 1492, a mere 39 years after the Byzantine Empire vanished from the map. Talk about shock waves. These are rapid geopolitical developments that literally set the stage for the modern world.

Thirdly, Saint Peter’s Basilica and the Vatican are considered the center of Christendom. But this is a relatively modern development. While Rome has always been central to the Christain world, Constantinople had Christianity’s greatest church, the Hagia Sophia. The great church still exists today but has since been converted into a mosque and museum in modern-day Istanbul. I’ve been there. I’ve seen it. And wow! It’s pretty spectacular for a building built 1,500 years ago. Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453 and the construction of Saint Peter’s Basilica went into rapid motion and was completed in 1506. The timing makes perfect sense if you understand the role the Byzantine Empire played in the drama.

Scholars mostly agree that the Medieval Era spanned the one-thousand years between 500-1,500 C.E. The Byzantines emerged when Rome fell in 476 C.E., and it ended when Constantinople fell in 1453. I mean, the Byzantine lifespan is the Middle Ages. Therefore, the Byzantine Empire literally bridges a misunderstood gap in time between you and me today, and our world’s most ancient societies.

Flags of the Ottoman, Hapsburg, and Russian Empire

Geographically, the Byzantine Empire merged into the Islamic Ottoman Empire, while culturally, it migrated northeast and into the Russian Empire, and geopolitically, the Byzantines became the Hapsburg Empire (the latter two even adopted the Roman-Byzantine ‘double-eagle’ on its flag). The Ottoman and Hapsburg Empires vanished in 1918, after World War 1. The Russian Empire, however, became the Soviet Union. The so-called “eastern bloc” of the Soviet Union included many of the former Byzantine states. Therefore, the mysterious lands of the Byzantines didn’t truly open up to the West again until 1991, when the Soviet Union finally collapsed. Amazingly, this is right around the time I checked out that library book that day in 1993.

So, why don’t we know more about the Byzantine Empire? I’ve never heard a good answer to this question. I’m a 43-year old man who’s still caught up in the thrill of a book I found when I was 17. I feel like an explorer who discovered a strange and exotic land, a kind of doppelganger to Western civilization as fantastic as Tolkien’s Middle-Earth, yet part of real history. Hopefully, we can finally take a look at the lost civilization that set the table for our modern age.

If you love history, I encourage you to read about Byzantium. Go down a rabbit hole or two. You just might discover a new passion too.

Douglas A. Burton is the author of the award-winning novel, ‘Far Away Bird,’ which comes out February 6th, 2020 and details Empress Theodora’s early life. The novel is available for pre-order in paperback (Amazon, Barnes & Noble) and as an amazing audiobook (Audible.com, iTunes, Author Republic). Learn more at douglasaburton.com.