Sep 14, 2023

There’s a tremor in the Force and the streaming series ‘Ahsoka’ on Disney+ is at the heart if it. Numerous opinions swirl around on social media, and it’s hard to make any sense of the conflicting accounts. Is ‘Ahsoka’ good or bad? I’ve been a vocal critic of the Ahsoka series, particularly the first two episodes. However, the show has steadily improved, and episode 5 turned my long-standing frustrations into real optimism. I’ll explore this episode, called ‘Shadow Warrior,’ and hopefully, I can break through the fog and explain what went right here…

***** WARNING: FULL SPOILERS AHEAD *****

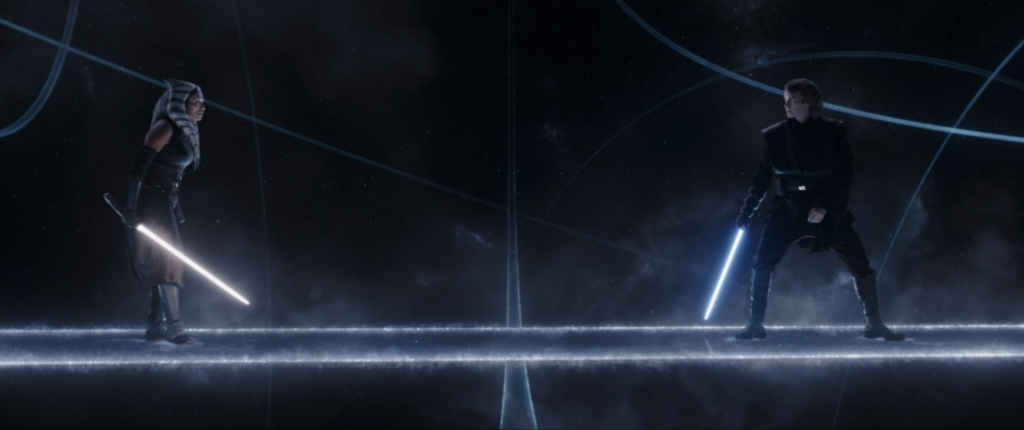

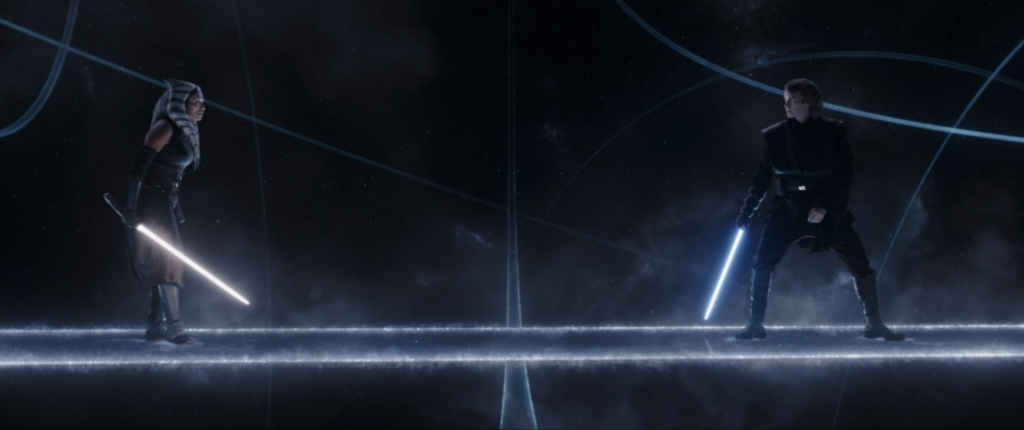

Anakin Skywalker, reprised by Hayden Christensen, appears in the show and has been dismissed as merely a figment of Ahsoka’s imagination. I firmly believe this is false. The cosmic environment where Anakin meets Ahsoka is called the World Between Worlds. It’s a real place in Star Wars canon, an interdimensional reality where the past, present, and future coexist. The past and future can be changed here. This meeting is the first ever between the fallen Jedi, Anakin Skywalker, and his loyal Padawan after the events of Return of the Jedi. The two have a deep history that spans seven seasons of the Animated hit series, The Clone Wars, and forms one of the great duos in all of Star Wars.

When Ahsoka fell from the cliff in episode 4, Anakin pulled her away from certain death and into the World Between Worlds. He’s really there in some form. She’s really there. That’s why Jacen can feel them in the Force even though Chopper can’t pick anything up on his scanner. That’s why Ahsoka is missing in the real world, where she fell. She isn’t dreaming.

While in the World Between Worlds, Anakin offers to finish Ahsoka’s training, which she accepts, even referring to him once again as “Master.”

The lesson is either “live or die,” relevant, considering Ahsoka just lost her fight with Baylan Skoll. She would be dead if not for Anakin pulling her into the World Between Worlds. So, choosing to live or die is the issue at hand for Ahsoka.

Anakin begins the lesson.

When Ahsoka declares, “I will not fight you,” Anakin eerily responds, “I’ve heard that before.” This line is an unmistakable call-back to Return of the Jedi when Luke Skywalker attempted this same strategy with Darth Vader. Ahsoka cannot know what Luke said to Vader in that final fight, so a figment of her imagination could not know that either. No. Only Anakin Skywalker knows that. And, as Vader did to Luke, Anakin presses Ahsoka into a deadly duel.

Folks, this is something we’ve never seen before if we stop to think about it. We see the continuation, at least in some form, of the only person who ever mastered the Good and the Dark Side of the Force. Obi-Wan, Yoda, and Qui-Gon could only teach their Padawans the Good side of the Force and warn against the Dark Side. Likewise, Palpatine could only teach the Dark Side. Never have we seen potent knowledge of light and dark in one mentor.

After the lightsaber battle lesson, Anakin sends Ahsoka falling into a vast liminal space. We see a younger Ahsoka, a girl, rise from the hazy mists into the dream world of her past. Clone troopers soon rush from out of the fog, having no beginning and no end, racing past Ahsoka only in the present moment, toward the unseen front line of a hazy battle in a doomed war.

We have returned to the symbolic Fall of humanity on a Galactic scale, the death of the Republic hangs in the air, and for the first time ever, we’re looking at these epic events through the eyes of an innocent. Ahsoka Tano inhabits the memory of her younger self with knowledge of the outcome. Jarred from her shock, young Ahsoka reluctantly follows the simple and seemingly hopeless command from Anakin, “Forward!” She lights her green lightsaber and advances into the void of nothingness.

The mentor and the pupil soon stand in the wake of battle amidst many fallen clones. Without a single spoken word, Ahsoka sits beside a clone trooper so wounded his face is fully covered. He cannot see or stand. But when Ahsoka takes his hand in a show of undisguised compassion, the clone trooper reaches back. They hold hands. Ahsoka cares about these living beings that lay like debris all around her.

She confronts Anakin about the cost of war. Anakin asserts that he, too, is bothered by the terrible loss of life. “This isn’t what I trained for,” says Ahsoka, acknowledging the shifting focus of the Jedi Order. Anakin tells her that the value of fighting and leadership is simply a matter of adapting to the times. He imparts the fateful wisdom of the era. “Look, when Obi-Wan taught me, we were keepers of the peace,” he says. Ahsoka worries here about her legacy. Is she to train her Padawan to fight? Anakin says in order to survive, “you’re gonna have to learn to fight.” Then, Ahsoka asks a child’s innocent question. “What if I want to stop fighting?”

“Then you’ll die,” he says, echoing the flawed wisdom that led the Jedi Order into an abyss of warfare, chaos, and forgotten virtues. “Let’s go,” says Anakin, lighting his lightsaber.

More clones rush past Ahsoka. She stands upon the battlefield and watches as the compassionate and heroic Anakin Skywalker heads out toward the horizon, leading yet another wave of clones to yet another position somewhere beyond the haze, his blue lightsaber out at his side. Under the flashing explosions of war, Anakin’s shape shifts seamlessly into Darth Vader holding a red lightsaber instead. And then, when the flashing subsides, we again see Anakin—the silhouette of perhaps the most tragic archetype from our modern mythology, shrinking in the distance as he continues steadily, relentlessly toward his fate.

And centered in the dreamlike battlefield stands the young Ahsoka Tano. The music rises as the camera closes in on her face. She’s visibly scared, perhaps terrified by the inevitability of the course of events. She’s trapped in the memory of a failed pupil from a fallen master. This is stunning imagery that hits me hard. I’ve watched it multiple times, and I get more emotional with each viewing.

What is the answer to this disastrous fate? What could have stopped it?

We return to Anakin and Ahsoka, this time on Mandalore. And here, again, we see that she’s concerned about her legacy. This is the Sacred Fire of both the Jedi order and our heroine. What is her purpose? What is she supposed to pass on? Anakin tells her that she’s more than just a fighter, just as he was more than just a fighter.

“You are more, Anakin,” she says. “But more powerful and dangerous than anyone realized.” And here, Anakin grows cold and begins a new lesson, only this is a lesson from the Dark Side of the Force. Anakin says, “I gave you a choice. Live or die.”

Ahsoka remains defiant. “No,” she says.

Then, after a chilling pause, the dark lord of the Sith cocks his head, “Incorrect.” Dressed as Anakin, Darth Vader launches a brutal flurry of attacks with his red lightsaber before kicking Ahsoka off her feet.

The fight resumes in the World Between Worlds, where Ahsoka finally bests Anakin. The camera shows a close-up of her face as she holds Vader’s saber to his neck, her every impulse to kill him showing in her momentary yellow eyes.

“I choose to live,” she says decisively.

And she means it. Ahsoka had feared her legacy would be death and destruction, just as Baylan said in the last episode. But when she has the chance to kill Darth Vader, Ahsoka chooses life. Ahsoka the gray, the indecisive, the watcher from the side lines, the lukewarm…is ready to grow and face the coming evils with conviction again, her missing quality.

The lesson is complete.

Vader closes his yellow Sith eyes and collects himself. When he looks again upon Ahsoka, we see the compassionate mentor return, the redeemed Anakin Skywalker, smile, and say, “There’s hope for you yet.”

Episode 5 captures the powerful archetypal symbols and feelings of storytelling that used to define Star Wars. It’s all there. I haven’t really seen it a long while. The ethics of force, the central power of individual choice, discipline versus seduction, good versus evil, life versus death, mentor and pupil—these are the themes that fuel the engine of Star Wars.

The master of the Good and Dark side of the Force has arrived. That mentor is Anakin Skywalker.

Ahsoka is then returned to the sea. She did not hold her breath all that time because she never hit the water when she fell. She was in the World Between Worlds, and Anakin has returned her intact, in the baptismal waters of change and renewal. When she awakens, she squints and mutters, “Anakin…”

WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT?

The Prequels ended in catastrophe and the loss of light in the galaxy. The original trilogy concluded with triumph over evil and the return of the Jedi. The question going forward is now what?

The rise of the New Republic means nothing without first facing the failures of the Galactic Republic from the prequels. The Jedi Order cannot return unless it changes. The new government will surely fail like the old one unless it changes. Now that the Empire has been defeated and the Jedi have returned, what do we do differently this time? What are the hard lessons from the catastrophe of Order 66 that caused the Empire to rise in the first place? And how do we learn to avoid that doom again going forward?

The sequel trilogy never answered these critical questions. Perhaps, the new regime at LucasFilm didn’t believe in Star Wars so much as they believed in their own hype.

And that is why they fail…

I believe there’s a plan here. I sense it. I don’t believe the sequel trilogy will be erased necessarily, not while the current regime is still in place at LucasFilm anyway. But I do believe that an alternate future is about to open up in the World Between Worlds, and Ahsoka will enter that future. Hopefully, the future of Star Wars will go with her.

Jul 9, 2021

Hollywood is mired in a new trend: heavy-handed feminism at the expense of the lead heroine. It’s bizarre. Black Widow joins an ever-growing list of top-tier heroines demoted through poor writing and scene-stealing tagalong characters. From Sarah Connor (Terminator: Dark Fate) to Wonder Woman (Wonder Woman 1984) to Rey (The Last Jedi & The Rise of Skywalker) to Mulan (Mulan 2020) to the numerous heroines in Game of Thrones, writers and filmmakers are flat out ruining heroines.

Despite being a secondary character in the Avengers saga, ScarJo always commanded an incredible on-screen presence. She’d stride through scenes with snappy quips, and a cool, casual confidence backed up by lethal fighting efficiency. Not even Captain America or Tony Stark upstaged Black Widow when they shared scenes. But in her standalone film, every other character tries to be the center of attention, yet none of them are more interesting than Natasha Romanov. She’s quiet and stays in the background. I think Scarlet Johansson has the fewest speaking lines in the whole movie. Most of the screen time and one-liners go instead to Florence Pugh, who plays Black Widow’s sister, Yelena. The movie’s cynical and dreary tone suits Yelena, who makes fun of Black Widow’s superhero poses and celebrity status as an Avenger.

Remember the Black Widow trailer we saw two years ago? Remember the scenes of practicing young ballerinas spliced with women training with handguns? I couldn’t wait to see the movie! Marvel seemed poised to deliver a Cold War origin story set in the Soviet Union where we’d see how Natasha Romanov became an international Avengers-level assassin. (Minor spoilers ahead) But nah! The opening sequence opened instead with a bland glimpse at Natasha’s preteen life in 1995 suburban Ohio. But her flashback actually serves as the back story for her Communist father more so than Natasha Romanov.

Why?

The film also leads off in a much less exciting post-Cold War Bill Clinton-era America. How does that complement a Black Widow origin story? And in the heyday of compact discs, the characters listen to a 1980’s cassette tape of a 1971 song, which totally distorts the 90’s era they’re trying to establish. Why? The tone is all over the place. The movie even misses minor opportunities. In 1995, little Natasha had blue hair dye. I don’t remember blue dye being a thing in 1995 but even so—since we’re dealing with the Black Widow’s origin story, why not show the future Black Widow with red hair dye?

And that was just the opening flashback.

Oddly, I never felt much of a connection to the big Avengers films while watching Black Widow. The characters make references to the Avengers, but the Marvel brand of optimism and fun just wasn’t here. I actually started shifting in my seat from boredom during the later action sequences, ready to get home and hang out with my wife.

The primary villain of Black Widow, someone named Dreykov, is an old man with no superpowers. He’s the most unthreatening, most boring villain ever to grace the MCU. But even worse, the movie wastes time setting up another “villain,” who strides into the film wearing a skull helmet. The name of this menacing supervillain? No idea. The movie never bothers to give “skull helmet” a supervillain name. When we get to the final battle, Black Widow just uses red magic mist to turn “skull helmet” to the good side. It was all a mistake. Folks, this is lazy writing that skips character growth and human change through storytelling and characterization.

The fog of Marvel’s decade-long success will hide Black Widow’s flaws for a while. Yes, Black Widow will score big at the box office, and yes, the corporate press will praise the movie as “amazing,” but I promise, Black Widow will not stand the test of time. The 24th film in the MCU is a clear step-down. I can’t imagine rewatching this film, and I can’t help but feel like yet another opportunity for a great heroine has been squandered.

Apr 13, 2021

For decades, Joseph Campell’s hero’s journey has been the primary model for narrative structure for writers around the world. This article is part of a series of articles that explores the “heroine’s labyrinth” as an alternative to the hero’s journey and focuses on the symbolism and archetypes of heroine-led fiction. Prior articles discussed the labyrinth versus the journey and examined the recurring villain archetype of the masked minotaur. This article goes right to the source of the heroine’s symbolic potential, her drive for individuation, and the competing forces that she must overcome. The sacred fire theme helps us understand the dynamism of conflict in heroine-led fiction.

Fire worship and sacred fires are intricately linked to mythology, folklore, and religion. In the novel, The Quest for Fire, prehistoric human tribes compete against each other to control fire, sometimes stealing away a burning log during a battle in hopes of keeping the fire ever-burning. Whoever has the fire, survives.

Fire usually represents a powerful, creative energy that can sustain life through heat, or bring light into darkness or craft materials to build tools or structures. But fire can just as easily represent a destructive force that can raze villages to ash, burn human beings, or spread violently out of control if mishandled. Therefore, fire is dual-natured in its potential for creation or destruction.

On the individual level, the sacred fire represents each person’s potential to be either an agent of creation or destruction. Such a powerful range of possibilities creates an ethical orientation for the heroine. Her choices matter. At the beginning of the story, the heroine is often depicted in an immature or inexperienced state. She’s becoming more aware of her agency, free will, or competency, which is to say, she’s becoming aware of her sacred fire. The heroine must claim her sacred fire by expressing some move toward greater freedom and expressing interest in the outside world.

There is a catch though.

The heroine’s claim upon her sacred fire introduces two other claimants—the native culture and the masked minotaur. Let’s take a closer look at the meaning behind all three claims to the sacred fire.

The Heroine’s Claim

The heroine’s sacred fire symbolizes her vast untapped, untested, and unrealized human potential. She has aspirations that exceed her current reality. The colorful and exotic native culture is just outside her window and the heroine intends to merge with that world. She’s aware of her potential and relies upon her imagination to compensate for her lack of experience. This vital pulse of the human spirit is relatable to all of us. We are stirred to the core when the heroine claims her sacred fire in fiction.

Musicals provide excellent examples of sacred fire moments because they are so brazen and memorable. Whatever forces have kept the heroine in her immature state, she’s ready to take a chance on herself and face the world. Elsa vows boldly to let it go. Moana declares her intent to see how far she’ll go. And poor Rapunzel wants to know just when will her life begin. And that’s just Disney. Sacred fire songs are common in many musicals, such as Dorothy Gale’s desire to go somewhere over the rainbow in The Wizard of Oz, or Roxy Hart’s dream to be the name on everybody’s lips in Chicago. These opening numbers are great examples of a heroine’s inner desire for self-actualization outside the labyrinth.

The “sacred fire” moment in the story, whether it’s a specific scene or a musical number, shows the audience or reader that the heroine has her own desires, her own vision, and her own unique outlook on the world. She’s ready. If done correctly, the heroine’s sacred fire moment can be incredibly powerful.

As readers or viewers, whenever the heroine claims her sacred fire, we feel the heroine’s first attempt at empowerment. All that unrealized potential is bubbling up and meeting us at a conscious and subconscious level. The heroine is building her will to act on her aspirations because she has found the words or actions to give force to the feeling. But while the heroine’s sacred fire moment throws a gauntlet at the world, trust me—the world responds to the challenge.

The Native Culture’s Claim

The heroine soon realizes that her native culture’s claim has been staked out long in advance. Whereas the symbolic power for the heroine is individual potential, the symbolic power of the native culture is communal continuity.

A continuous fire that burns through the passage of time links the present moment to the distant past when the flame had been first lit. If the flame goes out, then the continuity breaks—and whatever the flame represented is diminished in the world. All too often in heroine-centric stories, the native culture interprets continuity very narrowly as marriage and children. That’s why so many stories feature a socio-cultural labyrinth designed to steer the heroine toward the archetypes of the innocent virgin, the fertile bride, and the chaste mother—the three archetypes so prized by cultures worldwide.

Therefore, the labyrinth in a feminine monomyth symbolizes the long-standing and highly developed claim that society places upon the heroine.

Each one of us, men and women alike, stands atop trillions of decisions made by thousands of generations of human beings who solved the problems of survival and answered the questions of what it means to be human. They made decisions while facing annihilation by nature, subjugation from rival tribes or civilizations, and warding off collapse from within. Somehow, they made it and we exist today because our ancestors got something right. All fictional characters come from someplace geographically and speak a specific language. This inescapable anchor of human reality means that much of our personal identity comes down to us from something human that came before—our native culture. The phrase “passing the torch” is quite literally the passing of human knowledge, experience, ethics, skills, history, and survival strategies from one generation to the next.

The tension between the competing claims will immediately generate conflict. The sacred fire has been passed to the heroine, now she must pass the flame on to a new generation. But rearing children, while vital to survival, isn’t the only way a sacred fire can transfer from one generation to the next. Stories usually explore all the ways a heroine may contribute and in many cases, the heroine must overcome social expectations and pressures to pass on her sacred fire.

The transmission of specific ideas beyond animal instinct is a uniquely human aspect. Whether we’re talking about music, medicine, or good stories, ideas can also pass through time just as well as our genes. The heroine’s understanding of the world is still within the context of her culture—and so we must understand that the sacred fire that the heroine claims, did come down through the generations through the native culture. This makes the native culture’s claim to the sacred fire a powerful one.

Daenerys Targaryen in Game of Thrones provides an excellent example of the relationship between the heroine’s individuation and the influence of the native culture. First, she is a descendent of the Targaryen bloodline and so she inherits a title, a great house, a history, and the blood of the dragon, which means she cannot be burnt by fire. The three dragons are nearly perfect symbols of Daenerys’ growing potential for the creation of a better world or total destruction through conquest. Throughout the story, we see Daenerys struggle with moral decisions on a regular basis. She demonstrates an incredible individual will of her own and directs many events in the story on her rise to power. She’s as sovereign as they come. But we must not forget that her mission, her vision, and much of her orientation toward the world still stems from the sacred fire passed on to her from her native culture. She never forgets the Targaryen outlook on the world.

In the end, Daenerys oddly attempts to destroy forever the link between her powerful agency and the native culture from which she comes. And she fails.

In many stories, purging either one of the dual natures often leads the heroine to destroy either herself or the native culture, and both are tragic ends. If the heroine subordinates herself entirely to the native culture, she risks destruction at the total loss of self. Like a cult member, the heroine surrenders all individual agency for the demands of the group. Her world shrinks and the trapped heroine loses her human vitality and creative force.

But if the heroine rejects entirely the native culture from where her sacred fire originated, then she risks becoming lost in self-serving quests. She may even come to covet the sacred fire of others or seek out a substitute culture to compensate for the loss. These heroines may even become villains, such as Ursula from The Little Mermaid who gathers souls, or Agatha Harkness in WandaVision, who tries to physically steal Wanda’s sacred fire.

Bear in mind, the feminine monomyth isn’t confined to reinforce the claim of the native culture, but often the opposite. The heroine’s labyrinth is a natural storytelling model that shows us how to break gender norms, push back on social expectations, or challenge outdated traditions rather than blindly follow them. The general goal becomes the self-realization of the heroine’s individuation while also adding value to the continuity of the native culture.

Therefore, the heroine must achieve the proper balance between personal sovereignty and some form of continuity with the valuable human knowledge and experience that came before her.

And to add to this ancient conflict, there is yet a third claimant.

The Minotaur’s Claim

We already discussed the general attributes of the masked minotaur, namely, that they are almost always members of the native culture, they wear a socially acceptable mask while also hiding an oppressive side, and they exhibit a form of possessive love. But the symbolism of the sacred fire provides another layer of understanding about the masked minotaur.

In so many heroine-centric stories, the masked minotaur claims the heroine’s sacred fire for his or her own purposes. And where the native culture’s claim is socially pervasive, the minotaur’s claim is more individualized and self-serving. This selfish aspect introduces a dark and destructive force that threatens to monopolize the creative powers of the heroine. Therefore, the heroine must also overcome the minotaur’s pure and tyrannical claim to her sacred fire. In so many stories, the minotaur often covets the heroine’s feminine essence, her creative powers and energy, and yes, her beauty and eros. The minotaur is usually unable to see past these aspects of the heroine’s sacred fire.

In many heroine-centric stories, you’ll find common cause between the native culture and the masked minotaur. Whenever the minotaur appears as a potential suitor for the heroine, the possessive love of the minotaur aligns with the desire for continuity of the native culture through marriage (and children). Therefore, the native culture and the masked minotaur form a persistent alliance in heroine-centric stories.

In Titanic, the masked minotaur is Cal Hockley, who seeks to possess Rose Dewitt Bukater as his wife. Rose’s mother represents the interests of the native culture and implores Rose that the sacred fire might be extinguished if she doesn’t marry. Rose intuitively understands that accepting Cal’s offer of marriage will destroy her true inner self.

In Tangled, the sacred fire of the heroine is beautifully exemplified by the magic of Rapunzel’s hair. Her long hair is symbolic of her creative power because it restores youth and extends life. Mother Gothel, who is the masked minotaur, hordes the sacred fire to satisfy the vanity of eternal beauty. Locking Rapunzel in a tower perfectly captures the self-serving mentality of the minotaur’s claim. The heroine’s free will is devalued and suppressed.

Beauty and the Beast provides a perfect example of all three claims to the sacred fire being made at the same time. In the opening number, Belle expresses her sacred fire moment by wanting so much more than her provincial life. The townsfolk, on the other hand, make a bevy of remarks aimed at Belle’s non-conformity to the values of the native culture. And finally, Gaston is the masked minotaur of the story, who arrogantly claims Belle as his future wife. Everyone, it seems, seeks the sacred fire of the heroine for a different reason.

Protecting the Sacred Fire

By understanding the archetypal significance of the sacred fire, we can better appreciate the conflict of our favorite heroines. The opening scene to Star Wars: A New Hope, for example, takes on a whole new meaning. The film opens not with Luke Skywalker, but with Princess Leia. She’s desperately attempting to flee with the stolen plans to the dreaded Death Star. But the masked minotaur, Darth Vader, is bearing down on her in a menacing fashion (the head of the star destroyer even looks like a minotaur’s head).

On the surface, Vader is after the Death Star plans. But in archetypal and symbolic terms, Vader is after the deeper symbol that Princess Leia carries with her. She holds a fragile sacred fire—the life force of the entire Rebellion. If she fails, then the life of the Rebel Alliance will be put out across the galaxy. Subconsciously, we recognize that the flame—the continuity of the rebellion—is in Princess Leia’s hands as she races from danger. And the imagery in the film strikes at the very heart of our human subconscious.

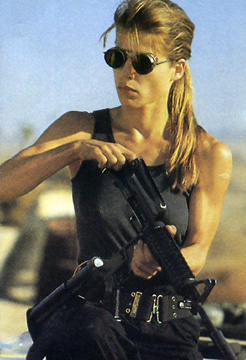

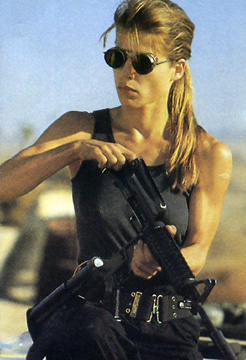

The same is true of Sarah Connor in the first two Terminator films. On the surface, Sarah is trying to survive because her unborn son, John Connor, is the future leader of the human resistance. So much criticism is directed at the idea that Sarah Connor plays second fiddle to John Connor, or that her value is confined to giving birth to a man who will save the world. But once again, we must look deeper into the symbolism. Sarah’s value extends far beyond motherhood. Think about it. Sarah would likely protect John’s life even if he was a tax accountant because most parents don’t need an excuse to protect children.

Screencap from Terminator 2: Judgment Day, TriStar Pictures 1991.

But Sarah isn’t just protecting one unborn child. She’s protecting three billion human lives from a future nuclear holocaust. Therefore, Sarah carries the eternal flame of all humanity. She carries humanity’s very right to exist. And our heroine is haunted by the sacred fire that she carries. When Sarah sleeps, her nightmares are not of John’s death, but of Judgement Day and the nuclear holocaust that obliterates billions of human beings. The story was never about John. It’s always been about Sarah and her desperate effort to protect the sacred fire from going out. That’s probably why subsequent films that centered on John Connor all failed, while Sarah Connor’s legacy has withstood the test of time.

Moana is just as much a story about Te Fiti as it is about Moana. Once again, like Princess Leia and Sarah Connor, Te Fiti carries the life force of the islands and sea. In the mythology of Moana, Te Fiti’s sacred fire is symbolized by the green Pulau stone. But the masked minotaur of the story, Maui, seeks to possess the goddess’ sacred fire and succeeds in stealing the Pulau stone. With her sacred fire stolen, Te Fiti becomes Te Ka, an angry goddess made of volcanic fire. She then becomes hostile and destroys life through the islands and sea. Only when Moana returns the sacred fire to Te Ka, does the goddess return to her original self. And life returns in spectacular fashion.

Sacred Fire in the Hero’s Journey

The sacred fire is not unique to heroine-centric stories. In fact, the basic concept is very much the same between both storytelling models. Like our heroines, our heroes also contend with the native culture for independence. The hero, too, can claim their sacred fire for creative or destructive purposes. However, the hero’s journey tends to emphasize the continuity of the native culture through the hero’s mastery of cultural skills and atonement with the father.

Probably one of the best examples of the sacred fire with a hero’s journey is the 1978 movie, Superman. The sacred fire is perfectly symbolized by the green crystal of Krypton. This glowing flame comes from the native culture and is passed to Clark. The crystal represents both the continuity of Krypton as well as Clark’s individual potential as Superman.

Summary

The sacred fire symbolizes the heroine’s vast human potential for creative good or destructive evil.

The heroine claims her sacred fire by expressing her personal desires, which then sets up the conflict between the heroine, the native culture, and the masked minotaur.

To the native culture, the sacred fire symbolizes the continuity of the tribe.

There remains a powerful bond between the heroine’s individual free will and her identity within the native culture.

The masked minotaur attempts to possess the sacred fire for selfish purposes

In the next article, we’ll explore the heroine’s first attempt to solve the three claims to her sacred fire–“the captivity bargain.”

Jan 11, 2021

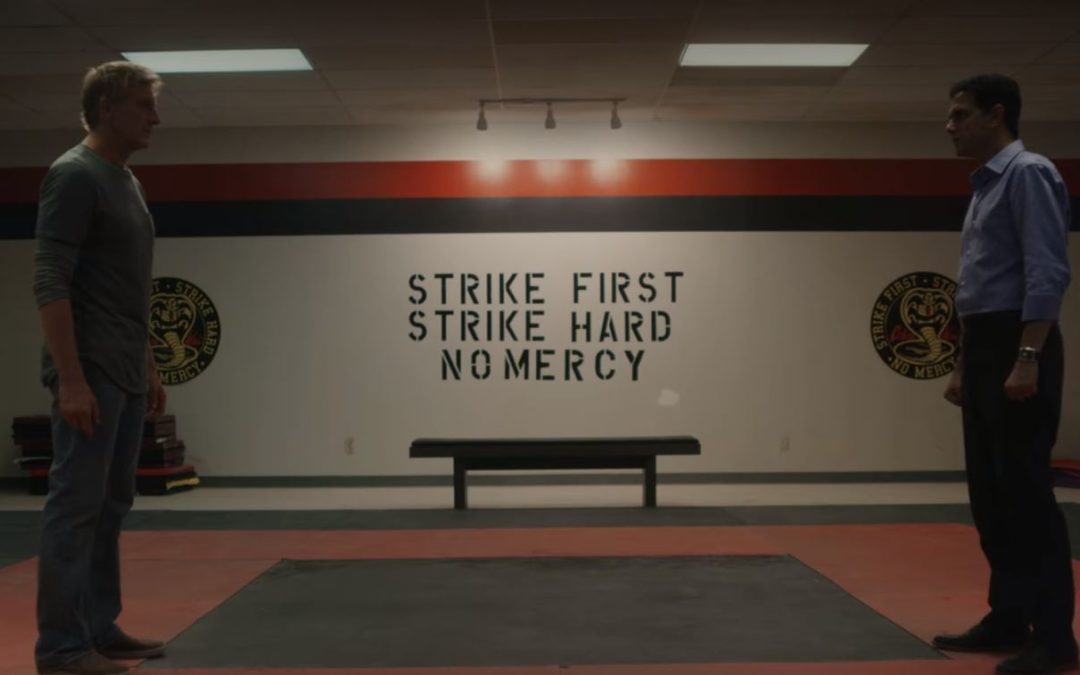

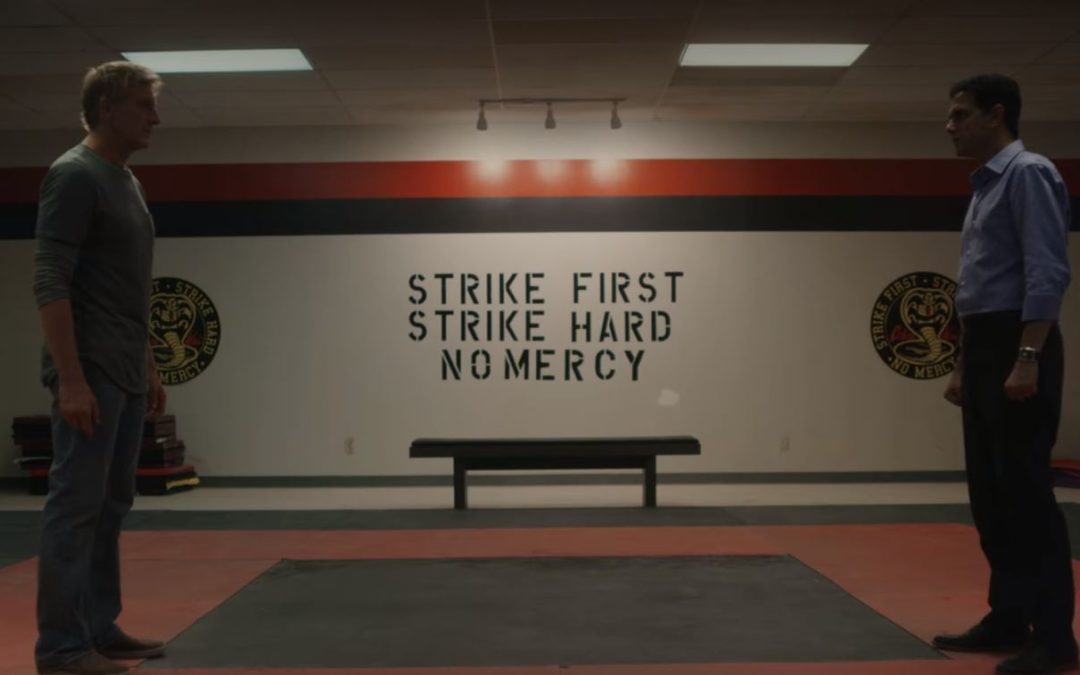

The calendar has flipped to 2021 and Cobra Kai, not Star Wars, is leading the way to the future of streaming entertainment. As of this writing, Cobra Kai is trending #1 on Netflix, gaining both critical acclaim and nearly universal praise. Like Star Wars, Cobra Kai shares its roots in 1980’s Generation X, and like Star Wars, Cobra Kai has mass appeal and an ethical framework wrapped into the brand. This article compares the Star Wars sequel trilogy to the first three seasons of Cobra Kai. (I’ll touch on the good news fromThe Mandalorian at the end of the article.)

Just five years ago, the Star Wars franchise appeared to be a resurgent juggernaut poised to dominate the galaxy for decades to come. But, oh, how quickly that all unraveled. After a divisive and baffling Episode 8, The Last Jedi, and box office flop, Solo, things suddenly looked shaky. Then, the incoherent Rise of Skywalker stumbled out and collapsed. Fans around the world knew then that Lucasfilm had lost its way. Joined the dark side, it had.

What can Daniel LaRusso and Johnny Lawrence teach Kylo and Rey?

A lot.

So, listen up, Lucasfilm, you’re not leading anymore. You’re playing catch up. Here are six common sense ideas to consider when writing shows going forward.

Stay Faithful to the Source Material

Imagine if the CEO of Coca-Cola decided that Coke’s secret recipe needed to go. Well, that’s pretty much the strategy Kathleen Kennedy put into place after taking the helm of Lucasfilm. George Lucas’ source material is the brand that makes Star Wars great. Even the clunky prequels have aged well—not because the movies were excellent—but because the overarching story was phenomenal. And yet, Lucasfilm demonstrated an almost pathological will to avoid the source material.

Not so with Cobra Kai. The writers absolutely love the source material and audiences can tell. The show consistently gets away with blatant flashbacks from the original films to bolster the ongoing themes. And it works because the writers understand how to follow the themes from the original film and repackage them for a modern audience.

Surprisingly, Cobra Kai successfully recycles its original villain, John Kreese, while adding more complexity and depth to the menacing sensei. The show even found a way to include nearly every character from the original films without pointless cameos. Even the most minor characters who return have an active and vital role in the story and character development.

Add Originality

Yeah, yeah, the general argument for hating source material stems from a misguided concern about tired old tropes. Vocal activists in the media declared Star Wars to be worn out and outdated. First off, not true. But originality doesn’t mean reinventing the entire brand from scratch. The Lucasfilm model of “subverting expectations” at the expense of your brand is and was a bad idea.

A good idea is to honor source material while boldly adding fresh new characters and storylines. Do both. Wax on and wax off. Passing the torch through mentorship is a perfect way to include legacy characters while introducing new characters. This contrast, alone, speaks volumes about the two mentalities. Star Wars treated portrayed their mentors as unwelcomed guests who had little, if anything, to teach. Cobra Kai, on the other hand, gave high respect to an older generation and the wisdom they could bestow.

Anchored firmly in the original films, Cobra Kai introduces a ton of new characters and solid plot lines. At times, I marveled at how the writers managed to get so much mileage out of the Karate Kid movies.

Indeed, Cobra Kai has a bevy of new characters, all with rich character arcs and never, never at the expense of the original characters. While the core audience loves following the rivalry of Johnny Lawrence or Danny Larusso, the new characters dominate the drama on a regular basis. Gen Z and Gen X form a nice alliance with strong messaging around self-reliance, self-defense, and anti-bullying.

Doing something new doesn’t mean destroying or disrespecting all that came before.

Focus on Good Writing & Characters

So many IP’s (intellectual properties) these days are “going woke” and for the life of me, I can’t understand why. Writing, story, and character development must never be subordinated to something as flimsy as an ideology. That’s called propaganda and audiences can smell that awful stench a mile away. In good writing, ethics emerge as a result of believable character actions and consequences.

While writing the scripts for Star Wars, Kathleen Kennedy, Rian Johnson, and others played a virtual game of Twister for the privilege of intruding on the script. A bad mix of adversarial feminism and moral relativism trampled Star Wars lore like a herd of drunken Banthas.

Whereas the Star Wars sequel trilogy is incoherent and sloppy, Cobra Kai is clean and well-written. The focus stays squarely on the characters and the conflicts that arise. The dialogue is excellent, humorous, and always echoes each character’s point of view. The script has fun with the rivalry between the Karate Kid and Johnny Lawrence but never takes itself too seriously.

And whereas Star Wars features such incredible writing blunders as killing off the main villain (Snoke) before developing any context or backstory, the decision to revisit the events of the first Karate Kid through the eyes of Johnny Lawrence was a stroke of genius.

Great writing, not ideology, will capture the imagination of audiences and stand the test of time.

Include Diversity, Ditch the Cringe

Diversity can be a great thing. But forced diversity turns people off, which then undermines the concept. The virtues of diversity are reduced to a campy ABC special that often leaves even diverse audiences rolling their eyes.

The Star Wars sequel trilogy increased diversity and relied on members of the press to praise them for doing so. With all the attention on diversity, the filmmakers focused on optics over the story. Rey is now a famous example of a Mary Sue rather than being a feminist icon or even just a great female heroine. Rose Tico, Finn, Admiral Holdo are other examples of bad diversity. An utter lack of toy sales for these characters furthers the point. Cringe kills, folks.

Cobra Kai understands that the story of the Karate Kid comes with a natural lesson about the value of diversity. Mr. Miyagi was Daniel Larusso’s mentor and sensei. The original films highlighted the power of eastern philosophy and Japanese wisdom that came with discipline and humility. The expanded range of perspectives impacted both characters. Diversity is part of what gave Daniel his edge in the final showdown. However, for a TV series that couldn’t include Mr. Miyagi directly, his presence looms large throughout all three seasons of the show, paying a sincere and meaningful tribute.

Diversity works best when writers don’t draw attention to it. Writers need to take the time to show us how diverse perspectives lead to innovation, creative problem solving, and character growth. If you’re serious about diversity, show us the magic in your story, don’t smother us in headlines.

Don’t Attack Any Demographic

Branding 101 emphasizing the relationship between your product and your target demographic. This is important because it personalizes the exchange and creates a positive experience with the brand. With the release of The Last Jedi, Lucasfilm changed tactics and adopted the mind-boggling strategy of driving off their legion of core customers, opting to build an entirely new customer base. It’s bizarre. This is the equivalent of the Sex and the City franchise targeting a blue-collar male audience while trashing femininity and quarreling with the numerous women who support the brand.

Somehow, the corporate custodians of one of the most prolific and profitable franchises in the world actually decided that the future of Star Wars should not be so damn Star Warsy. A deadly mixture of groupthink and ideology cooked up a superficial version of Star Wars and treated fan criticism as toxic. Instead of any sort of course correction, Lucasfilm turned on its fans like a death star blast. Oddly, the fans left, profits vanished, and the sequel trilogy has faded into cultural irrelevancy.

Cobra Kai, by contrast, isn’t ashamed to target and entertain the core demographic, while still maintaining progressive themes for anyone who wanted to follow the show. The universal appeal of Cobra Kai proves that a wide range of people can enjoy a good show. Despising any demographic within your fanbase reveals a shallow and dehumanizing mentality. Do we really need to go over this?

Get Gen X on Board

Lastly, Cobra Kai is shameless in its promotion of Gen-X culture and values. Author and lecturer, William Strauss, stated that Generation X is “by any measure the least racist of today’s generations.” There’s wisdom to be gained here.

Moreover, numerous marketing studies have discovered that Generation X is perhaps the most influential generation out there. Gen-Xers are extremely persuasive and often convince Gen Z, Millennials, and Baby Boomers to like what they like and buy what they buy. Genuine enthusiasm for great shows coupled with strong, independent opinions make Xers the perfect word-of-mouth fan. Cobra Kai gets it. Lucasfilm doesn’t.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t address that Lucasfilm might be coming around. The Mandalorian is a clear bright spot that holds a lot of promise. Why is The Mandalorian succeeding so far, where the sequel trilogy failed? The show follows all six lessons cited above. Let’s review:

- Stay Faithful to the Source Material

- Add Originality

- Focus on Good Writing & Characters

- Include Diversity, Ditch the Cringe

- Don’t Attack Any Demographic

- Get Gen X on Board

So, hopefully, under new leadership at Lucasfilm, the Force can be strong again. In the words of Mr. Miyagi, himself, “Never put passion in front of principle. Even if you win, you lose.”

Douglas A. Burton is an award-winning author whose current project centers on monomyth in storytelling and heroic women in fiction. For more, check out his website at douglasaburton.com

Dec 26, 2020

Wonder Woman 1984 is out at theaters and streaming freely on HBO Max! In 2017, Wonder Woman broke out to the adoring approval of women and men around the world, giving us all a top tier superheroine. This time around, Diana Prince had higher expectations but fell a bit short of the mark. The film isn’t terrible, but I just found myself irritated by the sloppy writing and incoherent plotlines, only to slip back into a stretch of satisfying viewing. Bizarrely, Wonder Woman is half Bruce Almighty and half Superman 4: The Quest for Peace.

Some critics completely trash the movie, while others heap gushing praise at the stunning and brave topics. Honestly, though, the film really doesn’t fall into either extreme category. In the end, I believe the Wonder Woman brand is left intact, but the clashing styles, bad plotlines, and mixed messaging will doom Wonder Woman 1984 to fade fast once the hype runs out.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Warning! Spoilers ahead.

We should give Wonder Woman 1984 some fair credit. The opening sequence is excellent. We get a great and fully realized depiction of Themyscira. The female-dominated society looked pretty awesome and I enjoyed the over-the-top obstacle course. Although I found it odd that a little girl would compete against seasoned female warriors in a goddess-level Olympics. I also liked that Diana cheats to try and win, only to be disqualified. Despite the dishonest effort to win, I was surprised that Diana avoids any serious scolding. I don’t know about you, but cheating in something like the Olympics carries a major stigma and is grounds for immediate public shame. The film largely glosses over the ethical dilemma and her mother instead lavishes young Diana with optimistic praise about seeking truth. The opportunity to teach Diana a lesson about tempering personal ambition or extraordinary ability was lost here.

I was pleased to see Diana Prince struggle more in this film. The persistent Mary Sue problem that stalks so many modern superheroines is mostly absent. I like Wonder Woman because she comes across as vulnerable and authentic. Wonder Woman even bleeds from a gunshot at one point and we discover that she’s losing her powers. But again, the rules for her “weakened” state are totally inconsistent. She still has her powers. She’s just “weakened” in a general, undefined sense, which made it hard to gauge the danger Wonder Woman faced at any given time.

Secondly, Gal Gadot delivers a solid performance. At times, I feel like the personal charisma of the actress, alone, is the driving force behind the success of the Wonder Woman franchise. Gal shows a wide range of emotions and manages to balance vulnerability and compassion with confidence and certitude, which isn’t always an easy balance.

I also found Chris Pine’s performance to be a good compliment. He and Gal have decent chemistry and his supporting role is positively portrayed. After seeing the trailer, I really doubted the film would provide an adequate reason for his reappearance 40 years later, but the film does explain it and it works. He was good and his presence gave the sequel a sense of continuity. However, the writers decided to give Steve Trevor a different body and face, as if he took possession of another human being. Then, the movie just plows ahead and pretends he’s Chris Pine anyway. WHY? This was so needlessly confusing and caused so many questions.

I heard a lot about the main villain being a Donald Trump knockoff as well. While the movie does attempt to make the comparison, in my opinion, the comparisons were pretty light. If anything, the movie devotes more time to knocking former president, Ronald Reagan.

I thought Kristen Wiig showed some potential as a secondary villain. For most of the film’s opening, she carried the villain origin story with excellent presence and intrigue. Then she gets lost. She resurfaces near the end for a showdown battle, but the epic fight took place in the dark. I could barely follow the action. The look for the supervillain, Cheetah, didn’t quite work either. I couldn’t quite follow how a socially awkward corporate woman ended up looking like a character from the play, Cats.

The problems with Wonder Woman 1984 are maddening because so many could have been fixed with better editing and adjustments to the script. Other problems arise in theme, pacing, and style. The golden armor, for example, is a good look, but totally mismatched to the situation. Wonder Woman doesn’t need the armor. It has no special powers. The golden armor is primarily symbolic of a woman’s stand against patriarchy, according to the backstory. But Wonder Woman dons that symbolic armor when she fights a female villain, so the symbolism is lost and devolves to a focus on style over substance.

There are scenes where she appears to be using her lasso to glide through the clouds. But then, at other times she appears to be able to control her physical body like Superman and shift directions. It’s actually never clear whether Wonder Woman can straight up fly.

And why the 1980’s? The setting seems to be hopelessly out of place and adds nothing to the dynamism and relevancy of Wonder Woman. When Steve Trevor tries to understand the 1980’s, I felt that the film trapped itself into a long montage of bringing him up to speed in comedic ways. Diana mostly follows a few paces behind Steve, grinning at his confusion. The movie goes over an hour without any serious Wonder Woman action. A plotline that tackles the nuclear arms build-up between the Soviet Union and the United States is outdated at best. Why not have a modern setting and tackle modern problems?

The invisible jet finally makes its appearance. The scene where Diana and Steve fly through a sky full of fireworks is one of the best sequences in the movie. But everything else is so dang clumsy. When Diana and Steve realize they must travel to Cairo, Egypt, they immediately decide to steal a museum jet rather than simply buy plane tickets. There’s absolutely no reason to break so many laws and resort to the theft of a military-grade vehicle. Diana remembers how to summon invisibility so off-handly that I wondered if the jet segment was added in post-production. The whole purpose behind the need for invisibility is specifically to avoid radar detection. However, the jet still physically passes through clouds, which means that radar waves can still locate them. Lastly, neither Diana’s ability to summon invisibility nor the invisible jet were ever mentioned again in the film. These are just lazy mistakes that go away with better writing.

The story then shifts to Egypt in a ham-fisted manner. Although the setting seemed to be out of place, I did enjoy some of the action between Wonder Woman and the armored vehicles. The superheroine pursuit came across as very entertaining and both my young sons reacted excitedly when Diana performed some larger-than-life superheroine moves—always a good sign. I particularly liked the scene where Wonder Woman is pinned between two armored vehicles and she strains to leg press them apart.

The film is also extremely loose on the nature of the villain and his actual abilities. He’s able to grant wishes. But sometimes, he seemed able to grant only one wish per person, and then at other times, he could grant multiple wishes. I never fully settled in with Maxwell Lord. He could trick people into making wishes by having them simply agree with a wish that he verbalized and then could simply name his price in return. It just seemed a little too easy. Twice, his son makes a wish to see his father more, which I thought would throw a monkey wrench into Maxwell Lord’s plans, but the film never follows up with the son’s wishes. And if the ending is meant to fulfill the son’s wishes, then did Maxwell Lord actually change through free will, or was it merely the effect of the wish?

Also, all the wishes in this film are negative. Not a single person wished for world peace or a cure for cancer. What happens when wishes are contradicted? When pressed to make a wish, why didn’t Diana wish for Maxwell Lord to lose his powers, or for the ancient artifact to be destroyed? This wish-fulfillment scenario was handled better in Bruce Almighty, where a comedy allows such an outrageous plot to both exist and yet be treated light-heartedly.

Despite all these criticisms, I still found some enjoyment watching Wonder Woman 1984. The character of Diana Prince as Wonder Woman is just plain likable. She comes across as genuine and serious as a superheroine. In many ways, I feel like good casting and solid acting compensate for the bad writing that mars the film. I can see many people watching and enjoying the movie, but the convoluted patchwork of a story won’t generate multiple viewings.

The first film featured mythological themes where Diana had to confront Ares, the god of war. So, facing off with a used car salesman and an insecure corporate woman seems like a major downgrade. I’d like to see some stronger themes for Wonder Woman. I’d like a deeper exploration of her struggles as a goddess among mortals. I want a more straight forward conflict. I’d like to see a stronger villain. And why doesn’t Wonder Woman get celebrity status or exciting press coverage in her world the way Superman, Batman, or Spiderman gets? That would add to her legend and mythology.

Ah well. We’ll get more Wonder Woman. And I think most of us will welcome her back for her third installment in the franchise. But the future of Wonder Woman is still grounded squarely in the success of the 2017 film.

Douglas A. Burton is an award-winning author whose current project centers on heroic women in fiction. For more, check out his website at douglasaburton.com

Dec 23, 2020

So, the season finale of the Mandalorian dropped last Friday, and Star Wars buzz is back in full swing. Reactions range from pure childhood elation to pleasant satisfaction to skepticism at Disney’s apparent shift away from the sequel trilogy. Whether you’re a casual Star Wars fan or a die-hard member of the Fandom Menace, you may want to chase that Mando high with more Star Wars. I did my homework over the last week and crafted a healthy list of the Star Wars shows that tie directly into Season 2 of The Mandalorian.

As of this writing, Mando is trending #1 on Disney Plus. No surprise there. But in 4th Place is a show called Star Wars: The Clone Wars and in 21st Place is another show called Star Wars: Rebels. These other two shows are trending because so much of what’s happening on The Mandalorian is heavily interconnected with these two other Star Wars shows. Ahsoka and Bo-Katan, for example, have some incredible backstories that are finding new light on The Mandalorian.

You need to get caught up!

Did you know that the Darksaber you saw in The Mandalorian has a massive backstory central to Mandalorian culture? Did you know that Ahsoka Tano was once Anakin Skywalker’s apprentice who survived Order 66 and helped start the rebellion? Did you know that Bo-Katan’s quest for the Darksaber can be traced to a duel for the throne of Mandalore against none other than Darth Maul?

Below is a list of episodes from both The Clone Wars and Rebels that tie directly to the events of The Mandalorian. Each episode is roughly 20 minutes long, so they are very easy to watch. Don’t be fooled by the fact that these shows are animated. The Clone Wars, especially, boasts award-winning animation that may never be surpassed, sometimes touching on spectacular. You‘ll see what all the hype is about—The Clone Wars carries all the gravitas of Star Wars while adding so many new characters and stories.

Star Wars: The Clone Wars

Season 1: Episode 19 Storm Over Ryloth

A solid introduction to Ahsoka Tano and her mentor-Padawan relationship with Anakin Skywalker. Ahsoka is no Mary Sue.

Season 2: Episode 5 Landing at Point Rain

A dramatic set-piece battle on Geonosis that’s better than the one in Attack of the Clones. Anakin, Obi-Wan, and Ahsoka all lead the Galactic Republic into combat.

Season 4: Episode 14: A Friend in Need

The introduction of Bo-Katan and the political civil war brewing on Mandalore

Season 5 – Three-Part Series

Episode 14 Eminence

Episode 15 Shades of Reason

Episode 16 The Lawless

This is the crux of the civil war on Mandalore and some of the best Star Wars there is. Darth Maul, Obi-Wan Kenobi, and Bo-Katan all lead different factions for control over Mandalore. You’ll even learn Obi-Wan’s most closely guarded secret and witness the shocking reunion between Darth Maul and Chancellor Palpatine.

Season 5 – Four-Part Series

Episodes 17 Sabotage

Episode 18 The Jedi Who Knew Too Much

Episode 19 To Catch a Jedi

Episode 20 The Wrong Jedi

These four episodes serve as a precursor to Order 66, centered on Ahsoka Tano and Anakin Skywalker. In my opinion, this mini-series is the best Star Wars subplot outside the Original Trilogy. After watching, you’ll know why Ahsoka Tano is revered by Star Wars fans around the world and why she’s getting her own series.

Season 7 – Four-Part Series

Episodes 9 Old Friends Not Forgotten

Episode 10 Phantom Apprentice

Episode 11 Shattered

Episode 12 Victory and Death

These four episodes came out earlier this year, just a few months before Season 2 of The Mandalorian. This miniseries features Bo-Katan, Anakin, Obi-Wan Kenobi, Darth Maul, and Ahsoka Tano and concludes the civil war on Mandalore. Even more incredible, the scenes overlap with Order 66, which fills the episodes with a palpable sense of dread.

Star Wars: Rebels

Season 2 – Two-Part Series

Episode 1 The Siege of Lothal Part 1

Episode 2 The Siege of Lothal Part 2

These two episodes are worth it for three reasons: James. Earl. Jones. He returns to voice Darth Vader and even pilots his custom TIE-fighter Advanced x1. Quite frankly, Rebels attached itself to Star Wars lore after these two episodes. Ahsoka Tano also returns to encounter Anakin’s presence for the first time since the Clone Wars.

Season 2 – Two-Part Series

Episode 21 Twilight of the Apprentice Part 1

Episode 22 Twilight of the Apprentice Part 2

Must-see Star Wars. Ahsoka Tano and Darth Vader cross lightsabers in a phenomenal confrontation that is as good as any in the whole Star Wars saga.

Season 3: Episode 15: Trials of the Darksaber

Bo-Katan debuts on Rebels and the plot behind the Darksaber resumes.

Season 3 – Two-Part Series

Episode 21 Zero Hour Part 1

Episode 22 Zero Hour Part 2

Grand Admiral Thrawn leads the Empire in a large set-piece space battle against the budding Rebel Alliance. (Remember, Ahsoka is seeking this very Grand Admiral in her episode of The Mandalorian.)

Season 4 – Two-Part Series

Episode 1 Heroes of Mandalore Part 1

Episode 2 Heroes of Mandalore Part 2

These two episodes pick up the drama on Mandalore and follow Bo-Katan’s effort to claim the Darksaber and restore order and pride to her people.

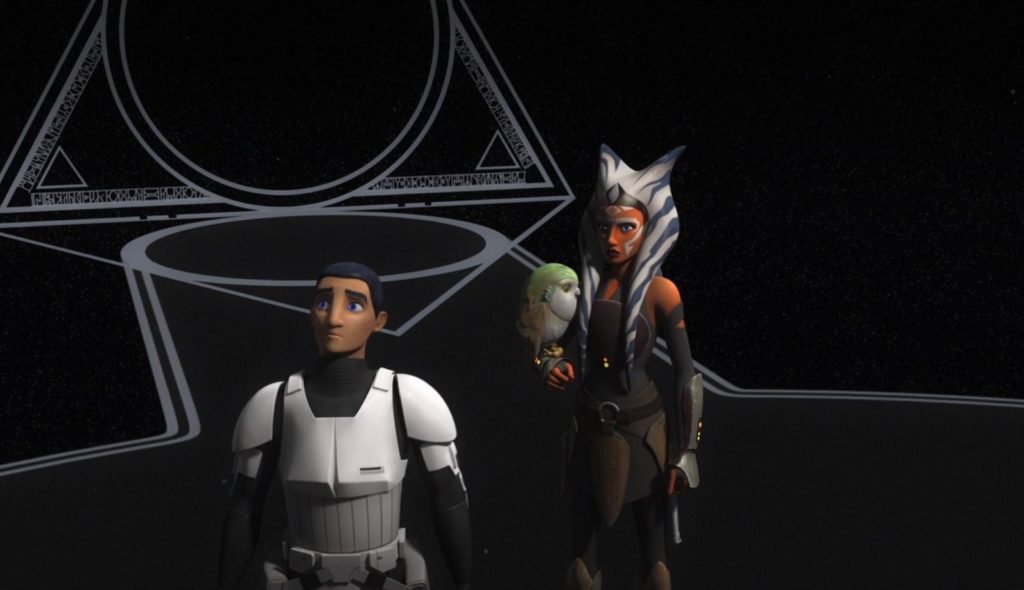

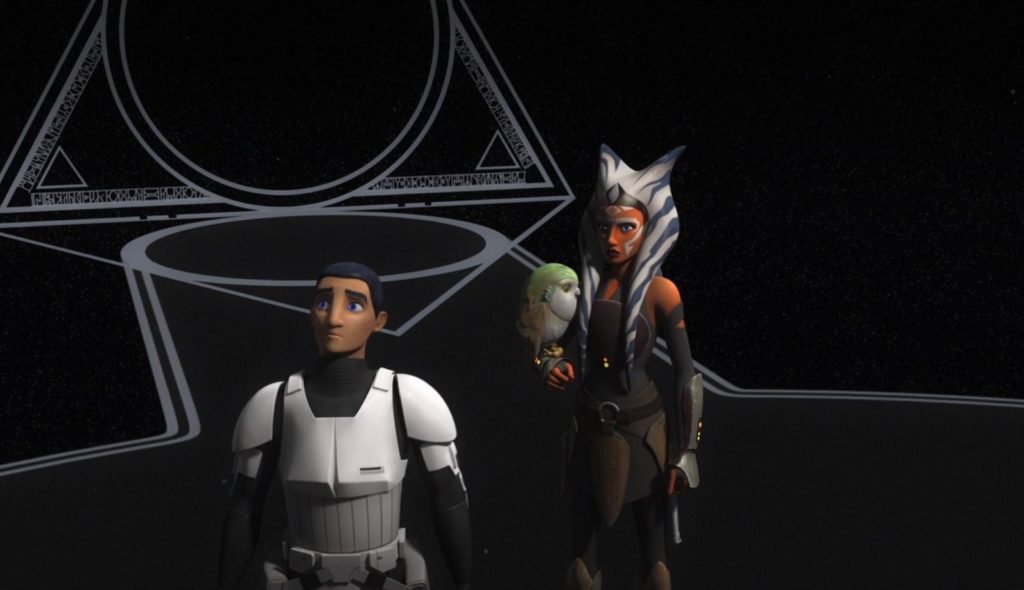

Season 4: Episode 13: A World Between Worlds

This episode is becoming the central focus for the future of Star Wars. Ahsoka discovers something called the Veil of the Force, which is a powerful nexus that can change events in the past. Take a look at the logo below for Ahsoka’s new show. The ‘O’ in her name is the actual symbol for the Veil of the Force. Strong speculation surrounds the possibility that the sequel trilogy will be overwritten, altered, or erased using the Veil of the Force.

There you have it, folks. These are the shows to watch until Season 3 of The Mandalorian.

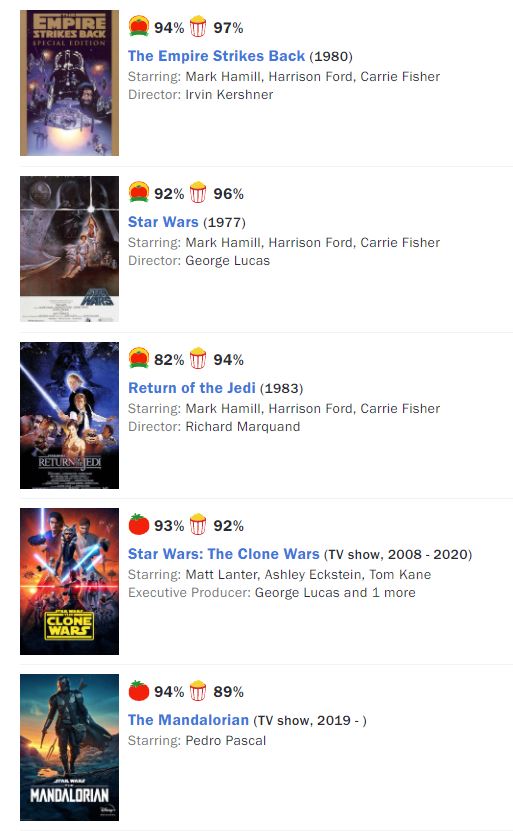

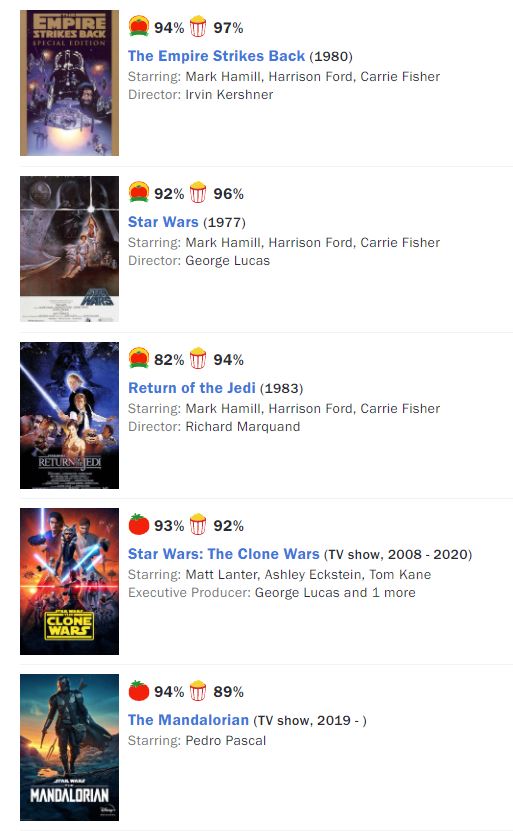

On Rotten Tomatoes, The Clone Wars is the highest fan-rated Star Wars story, just below the Original Trilogy and just above The Mandalorian.

Moreover, just a couple of weeks ago, Disney announced several new shows, such as Ahsoka, featuring Rosario Dawson as Ahsoka, The Book of Boba Fett, featuring Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett, Rangers of the New Republic, featuring Gina Carano as Cara Dune, and Obi-Wan Kenobi, which will feature both Ewan McGregor and Hayden Christianson as Obi-Wan Kenobi and Darth Vader, respectively. Some of these shows will likely surpass The Mandalorian in popularity. None of the new shows are spin-offs from the sequel trilogy.

Folks, Star Wars is moving away from the checkered sequel trilogy and toward a continuum of storylines from The Mandalorian, The Clone Wars, and Rebels.

So, get on board, Mando fans! Mando is leading us all right into the future of Star Wars.

Douglas A. Burton is an award-winning author whose current project centers on heroic women in fiction. For more, check out his website at douglasaburton.com