True hero’s journeys may be rarer than we previously thought. A journey that features a “departure” into exotic hinterlands is undoubtedly the stuff of cultural mythology. And yet, there are so many stories that don’t fit this mold. How else can we truly understand the story structure and character arc of Elisabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice? Or Janie Crawford in Their Eyes Were Watching God? Or Evelyn Wang in Everything Everywhere All at Once?

So, what makes the heroine-centric journey distinctive?

These heroines, just like Little Red Riding Hood and the Egyptian goddess, Isis, all faced conflicts within their native culture. From a pure storytelling standpoint, the heroine’s journey represents a fundamentally and existentially distinctive narrative model. So, let’s take a fresh look at heroine-centric stories. In order to fully appreciate the inward journey, we must first decouple it from the well-established hero’s journey.

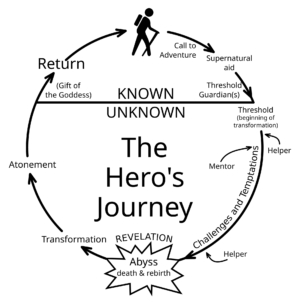

The Hero’s Journey: Quick Overview

Joseph Campbell based his hero’s journey mainly on male protagonists in multicultural mythology and literature. He refers to this cultural hunter-warrior as the “hero” of the story. The hero’s story manifests into a hero’s journey. Campbell demonstrated that the hero’s journey was archetypally primal, culturally transcendent, and surprisingly timeless. The hunter-warrior departs the native culture and encounters exotic dangers far from the daily rhythms of life at home. Therefore, we must recognize that the hero’s journey, as originally conceived, defines an outward journey away from the native culture. This “outwardness” is essential to Campbell’s model and may even be foundational to the premise.

In The Hero with A Thousand Faces, Campbell identifies the first stage of the story as the “Departure” and the final stage as the “Return.” He states that the hero transfers “his spiritual center of gravity from within the pale of society to a zone unknown.” A guarded threshold often exists between the familiar native culture and the unknown outer regions. Campbell describes the unknown as “a distant land, a forest, a kingdom underground, beneath the waves, or above the sky, a secret island, lofty mountaintops,” and later, as “desert, jungle, deep sea, alien land.” These are descriptions of wilderness terrain or foreign environments. The cultural hunter-warrior departs the familiar and protective native culture, encounters hostile dangers, delivers a decisive victory, experiences personal growth, and then returns home with a boon.

Challenging Campbell

Maureen Murdock, however, recognized that the journey of the cultural hunter-warrior placed women in a secondary and reductive role. In her book The Heroine’s Journey: A Woman’s Quest for Wholeness, Murdock laid out numerous stages in a woman’s life. Examples include the “Separation from the Mother” and the “Body/Spirit Split.” She offered alternative archetypal and psychological stages that didn’t appear in Campbell’s model. Murdock leaned heavily on the experiences and testimonies of her female contemporaries. The focus was less on storytelling and more on archetypal womanhood. Although Murdock didn’t design her book for writing craft, she proved that Campbell didn’t address numerous feminine themes and realities.

The Universal Hero’s Journey

Christopher Vogler also addressed the limitations of Campbell’s hero’s journey. For example, he helped make the monomyth more accessible by universalizing the hero’s journey. Instead of a direct departure and return, Vogler offers a transition from the “Ordinary World” into the “Special World.” The structural and conceptual adjustment replaces the essential outward journey with a more universal change in overall story settings or conditions. Instead of a cultural hunter-warrior, we get a universal and gender-neutral hero who begins the story in the Ordinary World and moves into an extraordinary Special World.

Moreover, Vogler removed the more male-oriented story stages, such as “The Meeting with the Goddess” and “Woman as Temptress.” Finally, he condensed Campbell’s stages, simplifying the basic structure, making it more inclusive and writer-friendly while preserving the core concepts. Most writers today actually rely on Vogler’s “universal hero’s journey” more so than Campbell’s “cultural hunter-warrior’s journey.”

The Campbell and Vogler models persist in modern storytelling, but Murdock’s assertion that numerous feminine archetypes are missing continues to ring true. We’ve settled for a compromise. Vogler’s universalization process built greater space for female protagonists, intermeshing their journeys into the overarching framework and addressing other nuances that transcended the original hunter-warrior premise. His efforts resulted in a structural model that applied to most journeys in general.

Separating the Inward Journey

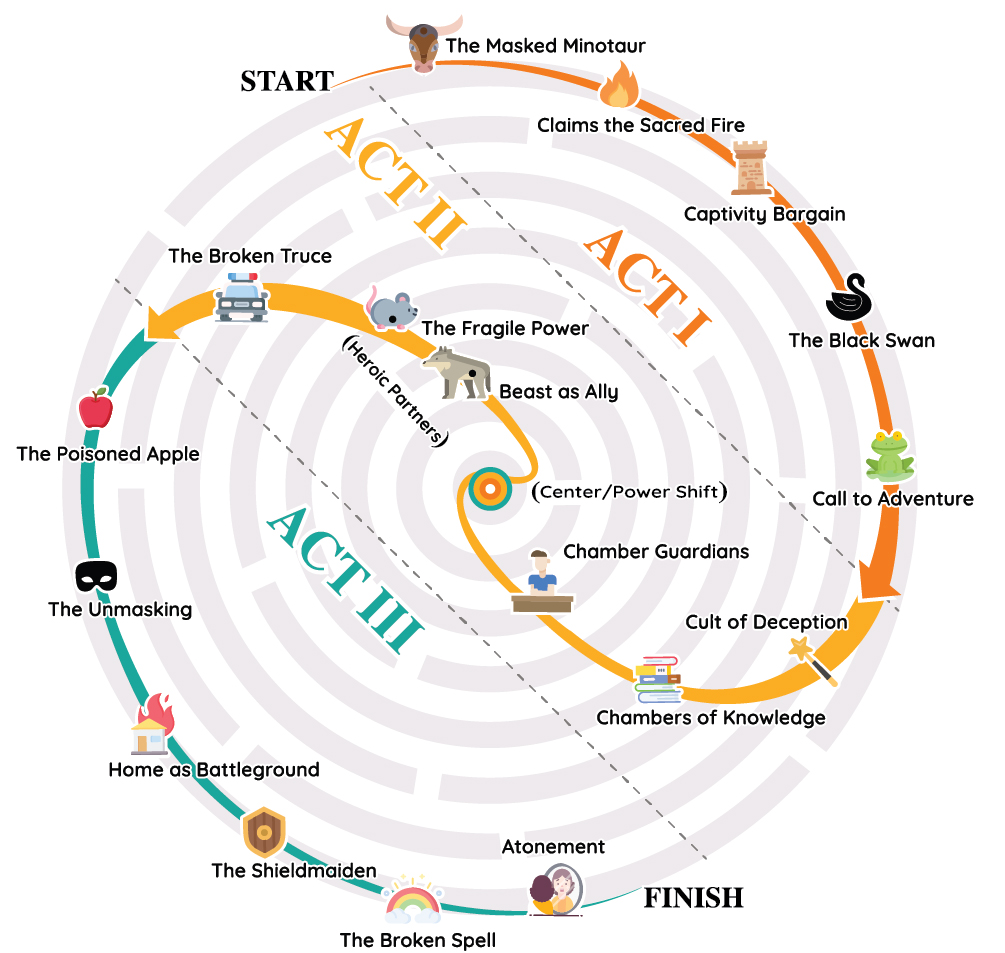

The time has come to separate the inward journey from the outward journey. Establishing the inward journey leaves Joseph Campbell’s cultural hunter-warrior and Vogler’s universal hero intact. However, we now have a clear third option that comes into focus—the heroine’s inward journey as a stand-alone, cross-cultural, and mythical experience. In keeping with the powerful resonance of the first two models, the heroine’s labyrinth exhibits feminine dynamism while also transcending gender altogether.

Below is the spiral design of the inward journey. The heroine travels deeper into the native culture before emerging out again. The growth arc features numerous distinctions.

Socio-Cultural Conflicts

The heroine’s labyrinth narrative model liberates itself entirely from the origins of a hunter-warrior story as modeled by mostly male protagonists. Secondly, the labyrinth separates itself even from the universalized hero’s journey, a variation rooted in Campbell’s departure and return. The heroine’s patterns and recurrent archetypes emerge authentically from stories with female protagonists once we affirm the structural uniqueness of the inward journey.

Instead of a departure from the native culture, we see countless heroines oriented to their societies, from which new but familiar conflicts take shape. Many heroine-centric stories also begin in the Ordinary World, as defined by Vogler, but develop a heightened focus on the social enculturation of the female protagonist. Heroines are often introduced to certain rules, gender roles, fixed traditions, superstitions, institutional methodology, social strategies, inherited customs, moral codes, community factions, family expectations, and cultural values. The confinement of the Ordinary World takes on greater significance because heroines didn’t always experience a total “departure” from society. The pressures of conformity within a social sphere did not establish “home” as a comforting place of safe returns. Instead, they lay the groundwork for a sustained conflict between culture and heroine throughout the story.

Hidden Mazes at Home

Culture itself becomes labyrinth-like for many heroines in fiction. Under wide-ranging cultural conditions, heroine-centric stories rarely feature a “threshold” beyond the native culture. Inside a labyrinth, a journey of many miles never strays far from the center, so a symbiotic relationship develops between the Ordinary and Special World for the heroine.

Why?

Because the Special World usually surrounds the heroine already. She sees and desires an unfiltered, unrestricted, and unprotected experience of her native culture. The heroine’s identity in the Ordinary World often prevents her from participating in the Special World. The two worlds are closer together in the heroine’s labyrinth–parallel–with the Special World hidden or forbidden. Even stories that appear to be an outward hero’s journeys require a second look. Heroine-centric stories such as Pan’s Labyrinth, Encanto, Alice in Wonderland, Labyrinth, Amélie, and Outlander all represent escapist journeys inside or near the heroine’s home. The events between the Ordinary and Special World are interrelated, and the decisions and consequences in one world affect the other.

In The Wizard of Oz, Coraline, Everything Everywhere All at Once, and Barbie have similar Special Worlds. Each “distant land” is actually a reimagining of the heroine’s home life with exotic doppelgangers of well-known friends, family members, or even themselves. Feelings of yearning, aspiration, and hope sit alongside feelings of frustration, repressed desire, and rebellion. We see the same socio-cultural conflicts in historical stories such as Memoirs of a Geisha, Jane Eyre, or I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. The journey is intimate and inward, familiar but different, yet strangely close to home. For the heroine, the unique relationship between the Ordinary and Special World replaces a linear outward threshold. The narrative experience is often both personal and deeply psychological. Therefore, the labyrinth perfectly symbolizing a full range of multilinear inward journeys–whether fantastical, realistic, or psychological.

Click here to see a six-minute video on the Labyrinth Archetype

Even in well-known short stories such as The Lottery by Shirley Jackson and The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, we see heroines at odds with their native culture. Their dangers are not far off, but nearby or inside the home. A cultural hunter-warrior or universal hero’s journey interpretation doesn’t adequately address the conflicts in heroine-centric stories. Campbell’s hero’s journey sidesteps most socio-cultural conflicts once the hero departs the home sphere. Vogler’s hero’s journey simplifies the Special World as a general shift in conditions. However, the heroine’s labyrinth elevates socio-cultural conflicts as a primary struggle. And so, we behold an alternative cultural figurehead in the heroine, whose growth doesn’t require a departure and return.

Different Journey, Different Villains

Villains, too, are affected by the structural reality of the inward journey. An overwhelming number of heroine-centric stories feature a duplicitous insider from within the native culture. Gone were the monstrous, out-in-the-open militant outsiders like Darth Vader, Thanos, the Kraken, Sauron, and Grendel. Instead of a “Distant Dragon,” heroines often face a dangerous “Masked Minotaur” from within their own native culture.

Heroines often encounter villains who are usually social apex characters. These villains appear pleasing or benevolent but hide a tyrannical side. The disguised or hidden villain brings an entire host of profound archetypal distinctions. These villains can come up close to the heroine, wield social power, and compromise the inner sanctums of society, if not the heroine’s home itself. A Masked Minotaur can also marshal social forces against the heroine. A desire to monopolize or possess the heroine often results in isolation or stigma. A villain disguised in the native culture is distinctive and archetypally profound. And like biblical Esther, the task of unmasking a socially esteemed villain often falls to the heroine.

See below for the heroine’s classic conflict triangle:

Inward Bound

The inward journey is timeless cross-cultural reality with deep archetypal truisms. The presence of distinctive archetypes along an inward journey does not invalidate the outward journey. The hero’s journey will likely remain the standard for an outward journey. However, the heroine’s labyrinth offers a new lens through which to examine and understand our stories.

In psychological, spiritual, and intellectual terms, the inward journey is nothing like the outward journey. Social anxiety, matters of personal identity, one’s role in society, pressure from trusted individuals, the social consequences of various relationships, disguised evils, professional endeavors, and navigating both public and private spheres all generate unique dangers, conflicts, and solutions. As such, the inward journey stands apart. The more we recognize the inward journey as a distinctive arc, the more we appreciate the labyrinth model. The heroine has much to teach us. The heroine’s story is our story; her struggles are our struggles, and her solutions provide a model of growth for all of us.

‘The Heroine’s Labyrinth: Archetypal Designs in Heroine-Led Fiction’ is a new approach to storytelling by author Douglas A. Burton. The writing craft book covers 18 unique archetypal patterns found in heroine-centric stories. Screenwriters, novelists, memoirists, and RPG gamers will all benefit from Burton’ fresh approach to storytelling.

I’m working on a heroine-centric story and am very excited to have found your website. I’d never heard of the heroine’s labyrinth before. I’ve been following Kim Hudson’s “The Virgin’s Promise” for my WIP, and the labyrinth offers a deeper perspective. Thank you!