Writing my book fundamentally changed me. In my effort to understand my lead heroine, Theodora, I uncovered a range of human experiences that were unfamiliar to me. The more I learned, the more I changed. The three central questions I get are why did you try to write from a woman’s perspective? What made you focus on such a sensitive issue? And what qualifies you to even write about this particular subject matter? I’m going to answer all three questions because the answers will also shed light on how I, myself, changed during my writing of the book.

So, why write from a female perspective? I didn’t see this as a particularly unusual matter, especially since there are plenty of women who’ve written male lead characters. But I guess it’s a curious question anyway. Back in 2009, I wrote, or attempted to write, a Byzantine novel written in the first person with Emperor Justinian as my main character. I wrote a whopping 500 pages and got lost in the woods. I never set up my major plot lines correctly, nor did I introduce important characters that would prove pivotal to the plot and climax. In short, I needed to learn more about story structure. I vowed to one day return and rewrite my Justinian epic, armed with the mysterious knowledge of story structure.

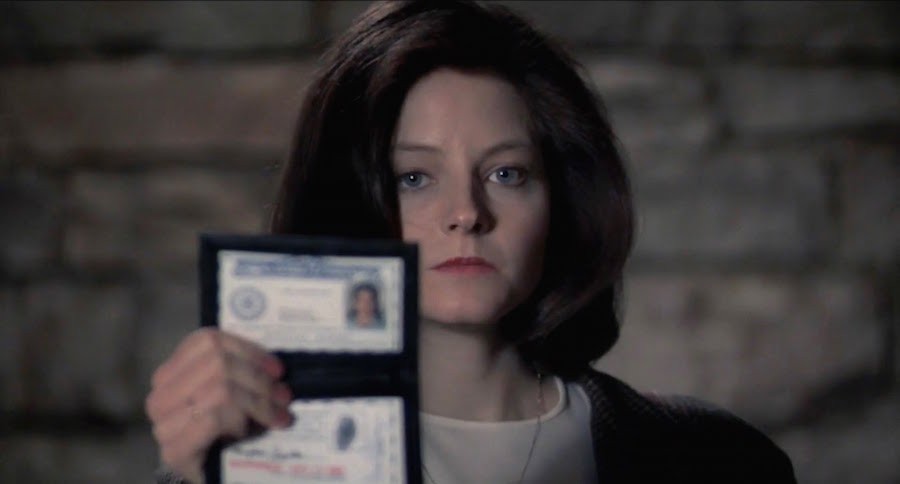

Over the next seven years, I broke down all my favorite movies—Star Wars, Amadeus, Silence of the Lambs, The Matrix, Aliens, Avatar, etc. I read Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces. I read all the great historical novels such as The Grapes of Wrath, For Whom the Bell Tolls, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Far Pavilions, Ben Hur, Gone with the Wind, and, yes, even War and Peace. After reading Memoirs of a Geisha, though, I wondered for the first time if Theodora, an actress-prostitute (and notorious exhibitionist), could work as a possible competing story line alongside my Justinian story. Perhaps I could portray the life of a Byzantine prostitute similar to the fascinating Japanese geisha I’d just read about. I wondered whether readers might find it interesting to see a future famous empress in this light. But I decided firmly against the idea because Theodora presented some unique problems. For one, showing a great female leader as a salacious prostitute instead of focusing on her accomplishments as an empress could be a really bad idea…worse than you think…

Let me explain.

There is an account of Empress Theodora’s early life that is so salacious that even I, despite admiring her historically, have struggled to reconcile. In what may be one of the greatest acts of gossip and defamation in history, the Byzantine historian, Procopius, tells a story of Theodora that has followed her through the centuries, a story regarding her portrayal of Leda and the Swan. No one reading or learning about Empress Theodora can be spared this story from her early life. I’ll let you read it for yourself. Here’s the X-rated excerpt from Procopius’ best-known work, The Secret History:

Often in the theater, too, in full view of all the people she would throw off her clothes and stand naked in their midst…she would spread herself out and lie face upwards on the floor. Servants on whom this task had been imposed sprinkle barley grains over her private parts, and geese trained for the purpose used to pick them off one by one with their bills and swallow them. Theodora, far from blushing when she stood up again, actually seemed to be proud of this performance. For she was not only shameless herself, but did more than anyone else to encourage shamelessness.

And Procopius goes on to say:

Never was anyone so completely given up to unlimited self-indulgence. Often she would go to a bring-your-own-food dinner-party with ten young men or more, all at the peak of their physical powers and with fornication as their chief object in life, and would lie with all her fellow-diners in turn the whole night long: when she had reduced them all to a state of exhaustion she would go onto their servants, as many as thirty on occasion, and copulate with every one of them; but even so she couldn’t satisfy her lust.

Procopius goes on and on. Even ‘fans’ of Theodora have to wince and wish they hadn’t read that. Check it out. Wikipedia mentions Leda and the Swan. It’s probably just gossip, but how could I possibly include Theodora’s early life and avoid this utterly unflattering story (along with all the other stories)? Even if I tried to ‘skip’ these accounts, readers would eventually discover them and any ‘untainted’ character portrayal of Theodora would risk collapse. Better to double down on Justinian’s story, and leave Theodora out of the book altogether.

But something happened to change my mind.

Based on a recommendation, I happened to be reading an utterly unrelated non-fiction book called Revolt of the Elites. I wasn’t even thinking about my unwritten Byzantine novel. Near the end of his book, the author attempts a deep-reaching analysis of politics and went into what seemed like a bizarre segue. He cites the work of a psychoanalyst, named Leon Wurmser, who published case studies on female exhibitionism. The psychoanalyst concluded that some of these women battled a deep inner shame and overcame the shame through acts of shamelessness. It’s a form of what’s called ‘counterphobia’ in which people engage excessively in something they fear as a defense mechanism. Here’s the exact passage I read regarding modern case studies:

…her fear of defilement and dishonor made her wish to defile others—a striking illustration of the connection between shameful disgrace and the shameless act of exposure. Another patient wished to hide her face from the world—the characteristic stance of shame—but also had a compulsion to exhibit herself. It was as if she were saying, “I want to show the world how magnificently I can hide.” Here, the rage for exposure was redirected to the self, in the form of an exhibitionism that “knew no shame,” as we used to say.

On the one hand, these patients wanted to see everything, as if they hoped to merge with the world through the medium of the eye. On the other hand, they wanted to dominate the world by making themselves objects of universal fascination. Fearing exposure, they wore the frozen, expressionless face Wurmser came to recognize as the mask of shame: “the immovable, inscrutable, enigmatic expression of a sphinx.” Yet this forbidding countenance served, in their fantasies, not only to hide their own secrets but to fascinate and dominate others, to punish others, as well, for attempting to penetrate their facades. The self-protective mask of shame was also the magically aggressive face of Medusa, which turns onlookers to stone.

By mentioning exhibitionism and shamelessness, I immediately thought again of Theodora and her early life as a “notorious” prostitute and exhibitionist. Did she fit this psychological profile? What if Theodora’s historical infamy was actually due to a childhood trauma? What if the trauma made her so ashamed that she engaged in excessive exhibitionism to overcome the trauma? What if she was actually suffering underneath the whole time? And what if overcoming the childhood trauma was the very thing that helped her become one of the greatest empresses in Byzantine history? Whoa. That seemed like a pretty big character arc.

I renewed my idea of a competing story line for Theodora. I always listen to music as part of my creative process. So, I was listening to this piece and an image popped into my head, an image of a young girl with her back to me. She was kneeling and praying alone in a medieval Byzantine basilica, not long after enduring a terrible abuse. She needed answers. She needed to know why. And she needed to understand why the world favored her rapist over her. These were rather brutal questions, but they resonated with me. That single image made me sympathize with the girl in my mind in a rather powerful way. It set in motion a glimpse of the path for Empress Theodora. The story would explain her salacious past in a new light, and at the same time offer an explanation as to what she had to overcome in order to become the stuff of empresses. It also explained why, after she became an empress, she made rape punishable by death, and why she helped to bring about dozens of laws designed specifically to help women. (She may have even been the first woman ever to truly act in a way consistent with a modern notion of women’s rights.)

In fact, now…instead of shying away from the lurid stories about Theodora, what if I confronted them head on? What if I left nothing out? What if I showed all her most defaming moments in the context of a woman who is attempting to brazenly DESTROY her inner shame at what happened to her? These questions stalked my mind for weeks. I also considered—in my loftiest daydreams—that if my book was ever actually successful, I could reverse the effects of Theodora’s 1,500-year smear campaign. People would know her worst stories, but instead of losing respect for her, they would see a heroine and an actual historical figure.

That’s why I wanted to write about a woman and that’s how the sensitive topic became central to the story.

I wrote out a few pages that tried to capture Theodora as a character and found myself immersed in her realities. I had terrible emotional reactions to the writing. But the more I wrote about her and her situation, the more engaged I felt. I even decided to drop my original plot line with Justinian entirely and to focus all my attention on Theodora.

But am I qualified to write about such abuses? The answer in my mind was a resounding “definitely not.”

Rape, abuse, and sexual assault are big and forbidden topics, especially for a guy without firsthand knowledge to be writing about. I feared (and still fear) that I’d become an unwelcome guest in a conversation that I had no business getting into. Clearly, I wasn’t including rape as a plot device—I saw it as the most likely causal event if the aforementioned case studies were to be believed. A sexual assault could easily create an unbearable shame that could force a girl to reinvent herself as sexually aggressive. It fit Wurmser’s psychological profile. So, I made the decision to be courageous and just write. But I challenged myself to get this right, to the best of my abilities.

I did have some things to draw upon. I have a cousin who experienced sexual abuse when she was very young, and I had a friend who was abused repeatedly by his older brother, and he, in turn, to his younger brother. Years before, both of them shared details and accounts about their experiences, even though I was extremely uncomfortable hearing these things at the time. I circled back to what they told me…I was listening now. The stories they had told me, though, didn’t always match the portrayal of rape I’d seen in movies, etc.

In movies, rape is often portrayed as a violent assault by an aggressive man or group of men. But, the more I read up on true accounts of rape, I discovered that many rapes occur by someone the victim trusted and in a way that was murkier, less obvious to the victim, often because they were young, inexperienced, or dealing with a man of high social status—social, professional, or even within a family.

In these scenarios, I learned that sexual attackers can create what I called a “confusion of consent.” The rapist attempts to convince or seduce the victim rather than risking a violent assault. In many cases, even the victim is left with some ambiguity, whether self-imposed or not, as to what actually happened. Obviously, blatant assaults occur too, but I found the seductive elements to be more horrible in a certain way, because the rapist inflicts a kind of persistent psychological residue that leaves the victim forever confused. The subtle assault is less obvious. Many victims can remember participating consciously or unconsciously in some kind of a lead up to the assault. Other times, victims were blindsided with improper requests by a person of high status. And once the rape takes place, victims are unlikely to speak out because of the powerful and oppressive “confusion of consent.” The waters are muddied. And if the rapist has any kind of high social status, then whatever benefits or favors the rapist is providing— both to the victim and indeed to all those who benefit from the rapist’s position—would be on the line if the victim were to challenge. The victim risks angering everyone and so finds an impossible circumstance of powerful social resistance to their tiny and unwanted claim to justice. This, too, started to hurt me just by trying to comprehend it. And I mean it. The injustice was quite large and would be in place and functional in any culture, in any time period, regardless of the moral norms. The motivation of the rapist would always be there and social nature of human beings would always establish a natural resistance to true resolution.

So, after understanding Theodora’s situation a little better, I had to turn to my villain. I have to get him right too. I learned why films portray male rapists as merely violent. Because as a writer, you cannot dare to give any redeeming qualities to such a man. He must be obviously evil and all evil. But I felt that readers needed to feel the nature of the subtle traps, since possibly, these were the most common traps. So, my villain would be a man of higher social status. My villain would hide in plain sight. He would be especially skilled at creating the “confusion of consent,” and he could deliver certain favors or benefits to Theodora that would make her question any challenge to him. He would deliver favors and benefits to many other people who surrounded Theodora. So, worst of all, the other people in Theodora’s world recognized and valued the social significance of her rapist and would become unexpected enforcers against her desire to challenge. No one will help Theodora challenge this villain, even if they knew what he did to Theodora. By challenging the villain, Theodora would become the villain to others. I felt certain that the villain I was about to create was real, and I knew this person existed around the world in many forms.

I also thought it was important to know who Theodora was before the assault. I had a feeling I knew this girl too. She’d have a positive self-image. She’d think highly of herself. She’d be optimistic and capable. She’d be smart and her ability to succeed would make her willing to take risks. And her innocence would allow her to completely underestimate the villain.

As I wrote about Theodora, I realized that I related to her in other ways. In my own life, I learned that when something really bad happens to you, people really don’t want to hear about it. They avoid you. You become an unwanted guest, viewed as toxic or negative. Wanting to talk about an injustice is bothersome. This part of her story I shared with her. I once lost everything and so, I knew also the sting of a social estrangement, a social collapse.

There were mornings, when after I wrote about Theodora, I’d go up for a shower, look in the mirror and see that my face looked pale. I felt heavy and constricted. I was uneasy for entire days. Trying to enter the head space of Theodora absolutely crushed my spirits sometimes. I’m not embarrassed to admit, there were many days that I cried. I’d get stuck in a stage of anguish from the leftover feelings of writing certain scenes or moments. My eyes were red and people could tell that I’d been crying. If I felt that bad after simply writing about these awful things, then I truly shuddered to imagine any human being who actually experienced this situation firsthand.

The time came for me to beta test my story, to come forward and allow strangers to read the pages I’d written in private about Theodora. My wife encouraged me to be brave about it. To my utter horror, I discovered that my writer’s group were all women. I had one question. When would they all turn against me for my clumsy foray into a room clearly marked “women only?”

To my utter surprise and extreme relief, every woman in that group had my back. They were supportive and engaged. They provided absolutely vital feedback in areas where I was still blind. These women helped me to understand my own lead character even better. And then, one of the writers informed me privately that she had actually experienced a rape in her recent past. That’s when it hit me: this shit’s real. The whole thing I’d been torturing myself trying to articulate was right up close. Real people I cared about were telling me about it. This woman offered to answer any questions I had, which I thought was unequivocally brave. She explained certain things to me, terrible and true details that I would have never known about, things that led me to grasp even more of the reality. Some of my more introverted writing peers left me feedback as well, peculiar feedback that led me to suspect they, too, had some experience with abuse, direct or through a friend, even if they didn’t outright tell me.

When a close friend of our family came over one night, a wonderful, witty, confident girl we’d known for years, and heard about my novel, she too, confessed that she’d been abused as a young girl. Suddenly, my cousin and old friend weren’t isolated stories from my past. The number of women with stories of abuse was getting uncomfortably crowded. And in an impossible coincidence of timing, the #MeToo movement struck in 2017 and my writing topic was now being echoed on national television. This signaled a devastating confirmation that abuse was indeed widespread and was occurring to women of all colors, all classes, all shapes, and sizes.

Suddenly, I saw how my conceptual “confusion of consent” could work on anyone, even the wealthy…even the strong ones. in fact, in what I deem as a truly awful paradox, women with high confidence and a strong self-image could actually see these positive qualities work against them…because a confident woman might not allow herself to acknowledge the awful truth of abuse. How could a high self-image exist side-by-side with a victim scenario? It sets up a perfect situation for self-denial. That actually made sense to me. That explained how a high-profile actress, CEO, or any successful woman could end up tweeting #MeToo. And then when I think about girls (or even boys) with lower self-esteem…I know in my heart that their desire or willingness to challenge their attacker would be reduced to an awful mode of silence.

So, yes, writing this book has had a big impact on me. I learned a terrible truth. That’s why I’ve chosen to go forward with this book on my own. While a child version of myself hopes for success, I care mostly about people getting something out of my story. I want others to experience a similar understanding to a problem that exists today, even if they, too, weren’t looking for it. I want people to learn about and be fascinated at Empress Theodora, because she’s a great woman in history. I believe she’s been obscured in history because the Byzantine Empire is obscured.

Circling back to the conception of the novel, I found again the passages by Procopius that I quoted earlier. He defamed Theodora for the last 1,500 years by telling us stories that shock and unsettle us when we think of Theodora. But, I challenge Procopius. I didn’t shy away from his slanderous description of Theodora. During the climax of my book, I actually have one of my characters speak aloud Procopius’ exact words, reconstructing the passage as dialogue, and setting the words one more time against Theodora directly. I put the defamation out there for all to hear and let the readers judge for themselves whether a sexualized woman is always guilty.

There is a fatalism to our greatest heroes and heroines. They dare where we recoil. I believe that this daring comes from losing a fear of death. In many ways, acts of evil kill the human spirit; they create a living experience not unlike death, right here in this world. That’s why, I guess, I believe heroes are tragic figures, even when they triumph, because sometimes, to triumph is to know that something like death has already visited them. Both the wound and healed scar are hidden from our eyes and so we see only their uncharacteristic bravery.

Theodora changed me for sure. I understand that the Hero’s Journey (or Heroine’s Journey in this case) is not such a glamorous thing if you let it all in. I learned about my own world and about problems that haven’t changed much whether we’re in the Sixth Century or the Twenty-First. I learned what #MeToo means on some deeper level. And I hope, if all goes well, that something as simple as a book can start conversations, thoughts, and solutions about what might solve the problems at hand. That’s why I’m willing to donate part of any profits from the book to a non-profit such as RAINN or the Joyful Heart Foundation.

So, that’s my tale as it relates to the sensitive subject matter of my book. There’s plenty more to the book and to Theodora, of course, but these issues seem to be at the heart of people’s curiosity and relevant to modern readers.