Claiming the Sacred Fire: Conflict in Heroine-Led Fiction

For decades, Joseph Campell’s hero’s journey has been the primary model for narrative structure for writers around the world. This article is part of a series of articles that explores the “heroine’s labyrinth” as an alternative to the hero’s journey and focuses on the symbolism and archetypes of heroine-led fiction. Prior articles discussed the labyrinth versus the journey and examined the recurring villain archetype of the masked minotaur. This article goes right to the source of the heroine’s symbolic potential, her drive for individuation, and the competing forces that she must overcome. The sacred fire theme helps us understand the dynamism of conflict in heroine-led fiction.

Fire worship and sacred fires are intricately linked to mythology, folklore, and religion. In the novel, The Quest for Fire, prehistoric human tribes compete against each other to control fire, sometimes stealing away a burning log during a battle in hopes of keeping the fire ever-burning. Whoever has the fire, survives.

Fire usually represents a powerful, creative energy that can sustain life through heat, or bring light into darkness or craft materials to build tools or structures. But fire can just as easily represent a destructive force that can raze villages to ash, burn human beings, or spread violently out of control if mishandled. Therefore, fire is dual-natured in its potential for creation or destruction.

On the individual level, the sacred fire represents each person’s potential to be either an agent of creation or destruction. Such a powerful range of possibilities creates an ethical orientation for the heroine. Her choices matter. At the beginning of the story, the heroine is often depicted in an immature or inexperienced state. She’s becoming more aware of her agency, free will, or competency, which is to say, she’s becoming aware of her sacred fire. The heroine must claim her sacred fire by expressing some move toward greater freedom and expressing interest in the outside world.

There is a catch though.

The heroine’s claim upon her sacred fire introduces two other claimants—the native culture and the masked minotaur. Let’s take a closer look at the meaning behind all three claims to the sacred fire.

The Heroine’s Claim

The heroine’s sacred fire symbolizes her vast untapped, untested, and unrealized human potential. She has aspirations that exceed her current reality. The colorful and exotic native culture is just outside her window and the heroine intends to merge with that world. She’s aware of her potential and relies upon her imagination to compensate for her lack of experience. This vital pulse of the human spirit is relatable to all of us. We are stirred to the core when the heroine claims her sacred fire in fiction.

Musicals provide excellent examples of sacred fire moments because they are so brazen and memorable. Whatever forces have kept the heroine in her immature state, she’s ready to take a chance on herself and face the world. Elsa vows boldly to let it go. Moana declares her intent to see how far she’ll go. And poor Rapunzel wants to know just when will her life begin. And that’s just Disney. Sacred fire songs are common in many musicals, such as Dorothy Gale’s desire to go somewhere over the rainbow in The Wizard of Oz, or Roxy Hart’s dream to be the name on everybody’s lips in Chicago. These opening numbers are great examples of a heroine’s inner desire for self-actualization outside the labyrinth.

The “sacred fire” moment in the story, whether it’s a specific scene or a musical number, shows the audience or reader that the heroine has her own desires, her own vision, and her own unique outlook on the world. She’s ready. If done correctly, the heroine’s sacred fire moment can be incredibly powerful.

As readers or viewers, whenever the heroine claims her sacred fire, we feel the heroine’s first attempt at empowerment. All that unrealized potential is bubbling up and meeting us at a conscious and subconscious level. The heroine is building her will to act on her aspirations because she has found the words or actions to give force to the feeling. But while the heroine’s sacred fire moment throws a gauntlet at the world, trust me—the world responds to the challenge.

The Native Culture’s Claim

The heroine soon realizes that her native culture’s claim has been staked out long in advance. Whereas the symbolic power for the heroine is individual potential, the symbolic power of the native culture is communal continuity.

A continuous fire that burns through the passage of time links the present moment to the distant past when the flame had been first lit. If the flame goes out, then the continuity breaks—and whatever the flame represented is diminished in the world. All too often in heroine-centric stories, the native culture interprets continuity very narrowly as marriage and children. That’s why so many stories feature a socio-cultural labyrinth designed to steer the heroine toward the archetypes of the innocent virgin, the fertile bride, and the chaste mother—the three archetypes so prized by cultures worldwide.

Therefore, the labyrinth in a feminine monomyth symbolizes the long-standing and highly developed claim that society places upon the heroine.

Each one of us, men and women alike, stands atop trillions of decisions made by thousands of generations of human beings who solved the problems of survival and answered the questions of what it means to be human. They made decisions while facing annihilation by nature, subjugation from rival tribes or civilizations, and warding off collapse from within. Somehow, they made it and we exist today because our ancestors got something right. All fictional characters come from someplace geographically and speak a specific language. This inescapable anchor of human reality means that much of our personal identity comes down to us from something human that came before—our native culture. The phrase “passing the torch” is quite literally the passing of human knowledge, experience, ethics, skills, history, and survival strategies from one generation to the next.

The tension between the competing claims will immediately generate conflict. The sacred fire has been passed to the heroine, now she must pass the flame on to a new generation. But rearing children, while vital to survival, isn’t the only way a sacred fire can transfer from one generation to the next. Stories usually explore all the ways a heroine may contribute and in many cases, the heroine must overcome social expectations and pressures to pass on her sacred fire.

The transmission of specific ideas beyond animal instinct is a uniquely human aspect. Whether we’re talking about music, medicine, or good stories, ideas can also pass through time just as well as our genes. The heroine’s understanding of the world is still within the context of her culture—and so we must understand that the sacred fire that the heroine claims, did come down through the generations through the native culture. This makes the native culture’s claim to the sacred fire a powerful one.

Daenerys Targaryen in Game of Thrones provides an excellent example of the relationship between the heroine’s individuation and the influence of the native culture. First, she is a descendent of the Targaryen bloodline and so she inherits a title, a great house, a history, and the blood of the dragon, which means she cannot be burnt by fire. The three dragons are nearly perfect symbols of Daenerys’ growing potential for the creation of a better world or total destruction through conquest. Throughout the story, we see Daenerys struggle with moral decisions on a regular basis. She demonstrates an incredible individual will of her own and directs many events in the story on her rise to power. She’s as sovereign as they come. But we must not forget that her mission, her vision, and much of her orientation toward the world still stems from the sacred fire passed on to her from her native culture. She never forgets the Targaryen outlook on the world.

In the end, Daenerys oddly attempts to destroy forever the link between her powerful agency and the native culture from which she comes. And she fails.

In many stories, purging either one of the dual natures often leads the heroine to destroy either herself or the native culture, and both are tragic ends. If the heroine subordinates herself entirely to the native culture, she risks destruction at the total loss of self. Like a cult member, the heroine surrenders all individual agency for the demands of the group. Her world shrinks and the trapped heroine loses her human vitality and creative force.

But if the heroine rejects entirely the native culture from where her sacred fire originated, then she risks becoming lost in self-serving quests. She may even come to covet the sacred fire of others or seek out a substitute culture to compensate for the loss. These heroines may even become villains, such as Ursula from The Little Mermaid who gathers souls, or Agatha Harkness in WandaVision, who tries to physically steal Wanda’s sacred fire.

Bear in mind, the feminine monomyth isn’t confined to reinforce the claim of the native culture, but often the opposite. The heroine’s labyrinth is a natural storytelling model that shows us how to break gender norms, push back on social expectations, or challenge outdated traditions rather than blindly follow them. The general goal becomes the self-realization of the heroine’s individuation while also adding value to the continuity of the native culture.

Therefore, the heroine must achieve the proper balance between personal sovereignty and some form of continuity with the valuable human knowledge and experience that came before her.

And to add to this ancient conflict, there is yet a third claimant.

The Minotaur’s Claim

We already discussed the general attributes of the masked minotaur, namely, that they are almost always members of the native culture, they wear a socially acceptable mask while also hiding an oppressive side, and they exhibit a form of possessive love. But the symbolism of the sacred fire provides another layer of understanding about the masked minotaur.

In so many heroine-centric stories, the masked minotaur claims the heroine’s sacred fire for his or her own purposes. And where the native culture’s claim is socially pervasive, the minotaur’s claim is more individualized and self-serving. This selfish aspect introduces a dark and destructive force that threatens to monopolize the creative powers of the heroine. Therefore, the heroine must also overcome the minotaur’s pure and tyrannical claim to her sacred fire. In so many stories, the minotaur often covets the heroine’s feminine essence, her creative powers and energy, and yes, her beauty and eros. The minotaur is usually unable to see past these aspects of the heroine’s sacred fire.

In many heroine-centric stories, you’ll find common cause between the native culture and the masked minotaur. Whenever the minotaur appears as a potential suitor for the heroine, the possessive love of the minotaur aligns with the desire for continuity of the native culture through marriage (and children). Therefore, the native culture and the masked minotaur form a persistent alliance in heroine-centric stories.

In Titanic, the masked minotaur is Cal Hockley, who seeks to possess Rose Dewitt Bukater as his wife. Rose’s mother represents the interests of the native culture and implores Rose that the sacred fire might be extinguished if she doesn’t marry. Rose intuitively understands that accepting Cal’s offer of marriage will destroy her true inner self.

In Tangled, the sacred fire of the heroine is beautifully exemplified by the magic of Rapunzel’s hair. Her long hair is symbolic of her creative power because it restores youth and extends life. Mother Gothel, who is the masked minotaur, hordes the sacred fire to satisfy the vanity of eternal beauty. Locking Rapunzel in a tower perfectly captures the self-serving mentality of the minotaur’s claim. The heroine’s free will is devalued and suppressed.

Beauty and the Beast provides a perfect example of all three claims to the sacred fire being made at the same time. In the opening number, Belle expresses her sacred fire moment by wanting so much more than her provincial life. The townsfolk, on the other hand, make a bevy of remarks aimed at Belle’s non-conformity to the values of the native culture. And finally, Gaston is the masked minotaur of the story, who arrogantly claims Belle as his future wife. Everyone, it seems, seeks the sacred fire of the heroine for a different reason.

Protecting the Sacred Fire

By understanding the archetypal significance of the sacred fire, we can better appreciate the conflict of our favorite heroines. The opening scene to Star Wars: A New Hope, for example, takes on a whole new meaning. The film opens not with Luke Skywalker, but with Princess Leia. She’s desperately attempting to flee with the stolen plans to the dreaded Death Star. But the masked minotaur, Darth Vader, is bearing down on her in a menacing fashion (the head of the star destroyer even looks like a minotaur’s head).

On the surface, Vader is after the Death Star plans. But in archetypal and symbolic terms, Vader is after the deeper symbol that Princess Leia carries with her. She holds a fragile sacred fire—the life force of the entire Rebellion. If she fails, then the life of the Rebel Alliance will be put out across the galaxy. Subconsciously, we recognize that the flame—the continuity of the rebellion—is in Princess Leia’s hands as she races from danger. And the imagery in the film strikes at the very heart of our human subconscious.

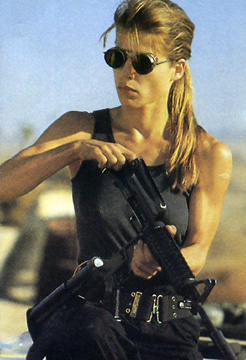

The same is true of Sarah Connor in the first two Terminator films. On the surface, Sarah is trying to survive because her unborn son, John Connor, is the future leader of the human resistance. So much criticism is directed at the idea that Sarah Connor plays second fiddle to John Connor, or that her value is confined to giving birth to a man who will save the world. But once again, we must look deeper into the symbolism. Sarah’s value extends far beyond motherhood. Think about it. Sarah would likely protect John’s life even if he was a tax accountant because most parents don’t need an excuse to protect children.

Screencap from Terminator 2: Judgment Day, TriStar Pictures 1991.

But Sarah isn’t just protecting one unborn child. She’s protecting three billion human lives from a future nuclear holocaust. Therefore, Sarah carries the eternal flame of all humanity. She carries humanity’s very right to exist. And our heroine is haunted by the sacred fire that she carries. When Sarah sleeps, her nightmares are not of John’s death, but of Judgement Day and the nuclear holocaust that obliterates billions of human beings. The story was never about John. It’s always been about Sarah and her desperate effort to protect the sacred fire from going out. That’s probably why subsequent films that centered on John Connor all failed, while Sarah Connor’s legacy has withstood the test of time.

Moana is just as much a story about Te Fiti as it is about Moana. Once again, like Princess Leia and Sarah Connor, Te Fiti carries the life force of the islands and sea. In the mythology of Moana, Te Fiti’s sacred fire is symbolized by the green Pulau stone. But the masked minotaur of the story, Maui, seeks to possess the goddess’ sacred fire and succeeds in stealing the Pulau stone. With her sacred fire stolen, Te Fiti becomes Te Ka, an angry goddess made of volcanic fire. She then becomes hostile and destroys life through the islands and sea. Only when Moana returns the sacred fire to Te Ka, does the goddess return to her original self. And life returns in spectacular fashion.

Sacred Fire in the Hero’s Journey

The sacred fire is not unique to heroine-centric stories. In fact, the basic concept is very much the same between both storytelling models. Like our heroines, our heroes also contend with the native culture for independence. The hero, too, can claim their sacred fire for creative or destructive purposes. However, the hero’s journey tends to emphasize the continuity of the native culture through the hero’s mastery of cultural skills and atonement with the father.

Probably one of the best examples of the sacred fire with a hero’s journey is the 1978 movie, Superman. The sacred fire is perfectly symbolized by the green crystal of Krypton. This glowing flame comes from the native culture and is passed to Clark. The crystal represents both the continuity of Krypton as well as Clark’s individual potential as Superman.

Summary

The sacred fire symbolizes the heroine’s vast human potential for creative good or destructive evil.

The heroine claims her sacred fire by expressing her personal desires, which then sets up the conflict between the heroine, the native culture, and the masked minotaur.

To the native culture, the sacred fire symbolizes the continuity of the tribe.

There remains a powerful bond between the heroine’s individual free will and her identity within the native culture.

The masked minotaur attempts to possess the sacred fire for selfish purposes

In the next article, we’ll explore the heroine’s first attempt to solve the three claims to her sacred fire–“the captivity bargain.”