Aug 8, 2024

True hero’s journeys may be rarer than we previously thought. A journey that features a “departure” into exotic hinterlands is undoubtedly the stuff of cultural mythology. And yet, there are so many stories that don’t fit this mold. How else can we truly understand the story structure and character arc of Elisabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice? Or Janie Crawford in Their Eyes Were Watching God? Or Evelyn Wang in Everything Everywhere All at Once?

So, what makes the heroine-centric journey distinctive?

These heroines, just like Little Red Riding Hood and the Egyptian goddess, Isis, all faced conflicts within their native culture. From a pure storytelling standpoint, the heroine’s journey represents a fundamentally and existentially distinctive narrative model. So, let’s take a fresh look at heroine-centric stories. In order to fully appreciate the inward journey, we must first decouple it from the well-established hero’s journey.

The Hero’s Journey: Quick Overview

Joseph Campbell based his hero’s journey mainly on male protagonists in multicultural mythology and literature. He refers to this cultural hunter-warrior as the “hero” of the story. The hero’s story manifests into a hero’s journey. Campbell demonstrated that the hero’s journey was archetypally primal, culturally transcendent, and surprisingly timeless. The hunter-warrior departs the native culture and encounters exotic dangers far from the daily rhythms of life at home. Therefore, we must recognize that the hero’s journey, as originally conceived, defines an outward journey away from the native culture. This “outwardness” is essential to Campbell’s model and may even be foundational to the premise.

In The Hero with A Thousand Faces, Campbell identifies the first stage of the story as the “Departure” and the final stage as the “Return.” He states that the hero transfers “his spiritual center of gravity from within the pale of society to a zone unknown.” A guarded threshold often exists between the familiar native culture and the unknown outer regions. Campbell describes the unknown as “a distant land, a forest, a kingdom underground, beneath the waves, or above the sky, a secret island, lofty mountaintops,” and later, as “desert, jungle, deep sea, alien land.” These are descriptions of wilderness terrain or foreign environments. The cultural hunter-warrior departs the familiar and protective native culture, encounters hostile dangers, delivers a decisive victory, experiences personal growth, and then returns home with a boon.

Challenging Campbell

Maureen Murdock, however, recognized that the journey of the cultural hunter-warrior placed women in a secondary and reductive role. In her book The Heroine’s Journey: A Woman’s Quest for Wholeness, Murdock laid out numerous stages in a woman’s life. Examples include the “Separation from the Mother” and the “Body/Spirit Split.” She offered alternative archetypal and psychological stages that didn’t appear in Campbell’s model. Murdock leaned heavily on the experiences and testimonies of her female contemporaries. The focus was less on storytelling and more on archetypal womanhood. Although Murdock didn’t design her book for writing craft, she proved that Campbell didn’t address numerous feminine themes and realities.

The Universal Hero’s Journey

Christopher Vogler also addressed the limitations of Campbell’s hero’s journey. For example, he helped make the monomyth more accessible by universalizing the hero’s journey. Instead of a direct departure and return, Vogler offers a transition from the “Ordinary World” into the “Special World.” The structural and conceptual adjustment replaces the essential outward journey with a more universal change in overall story settings or conditions. Instead of a cultural hunter-warrior, we get a universal and gender-neutral hero who begins the story in the Ordinary World and moves into an extraordinary Special World.

Moreover, Vogler removed the more male-oriented story stages, such as “The Meeting with the Goddess” and “Woman as Temptress.” Finally, he condensed Campbell’s stages, simplifying the basic structure, making it more inclusive and writer-friendly while preserving the core concepts. Most writers today actually rely on Vogler’s “universal hero’s journey” more so than Campbell’s “cultural hunter-warrior’s journey.”

The Campbell and Vogler models persist in modern storytelling, but Murdock’s assertion that numerous feminine archetypes are missing continues to ring true. We’ve settled for a compromise. Vogler’s universalization process built greater space for female protagonists, intermeshing their journeys into the overarching framework and addressing other nuances that transcended the original hunter-warrior premise. His efforts resulted in a structural model that applied to most journeys in general.

Separating the Inward Journey

The time has come to separate the inward journey from the outward journey. Establishing the inward journey leaves Joseph Campbell’s cultural hunter-warrior and Vogler’s universal hero intact. However, we now have a clear third option that comes into focus—the heroine’s inward journey as a stand-alone, cross-cultural, and mythical experience. In keeping with the powerful resonance of the first two models, the heroine’s labyrinth exhibits feminine dynamism while also transcending gender altogether.

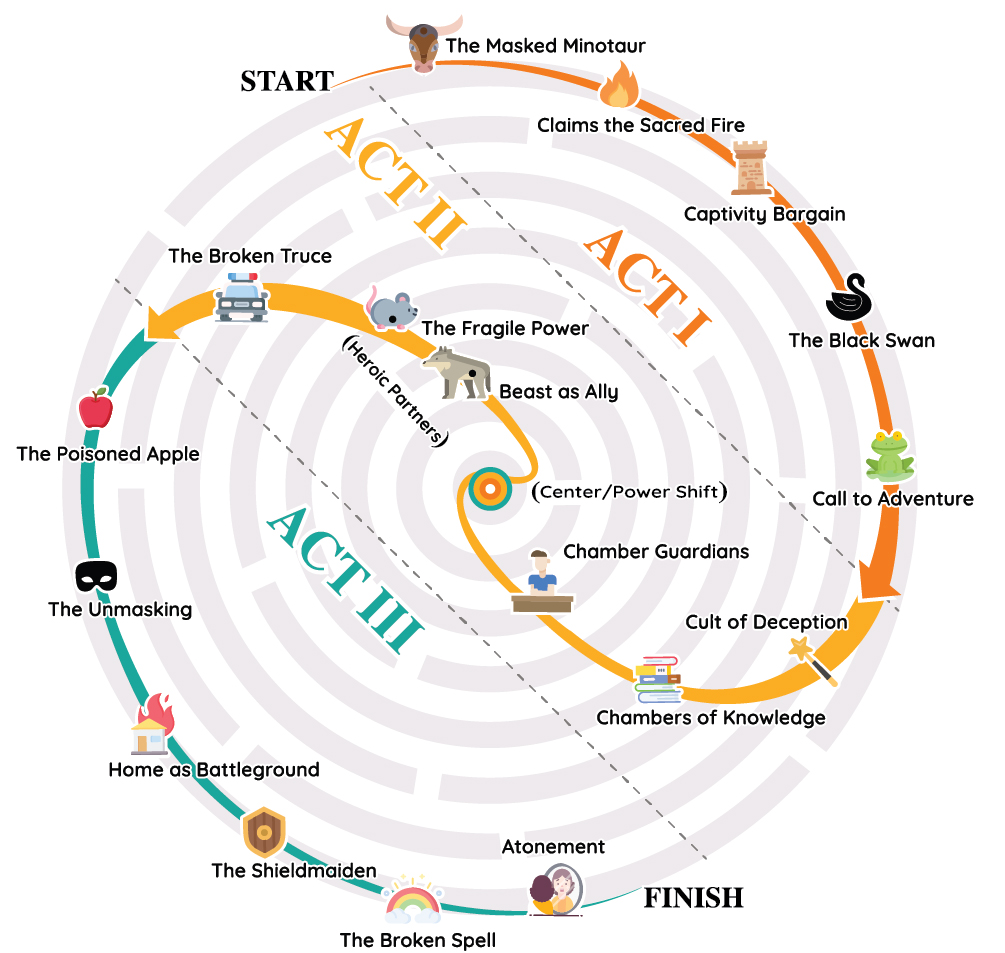

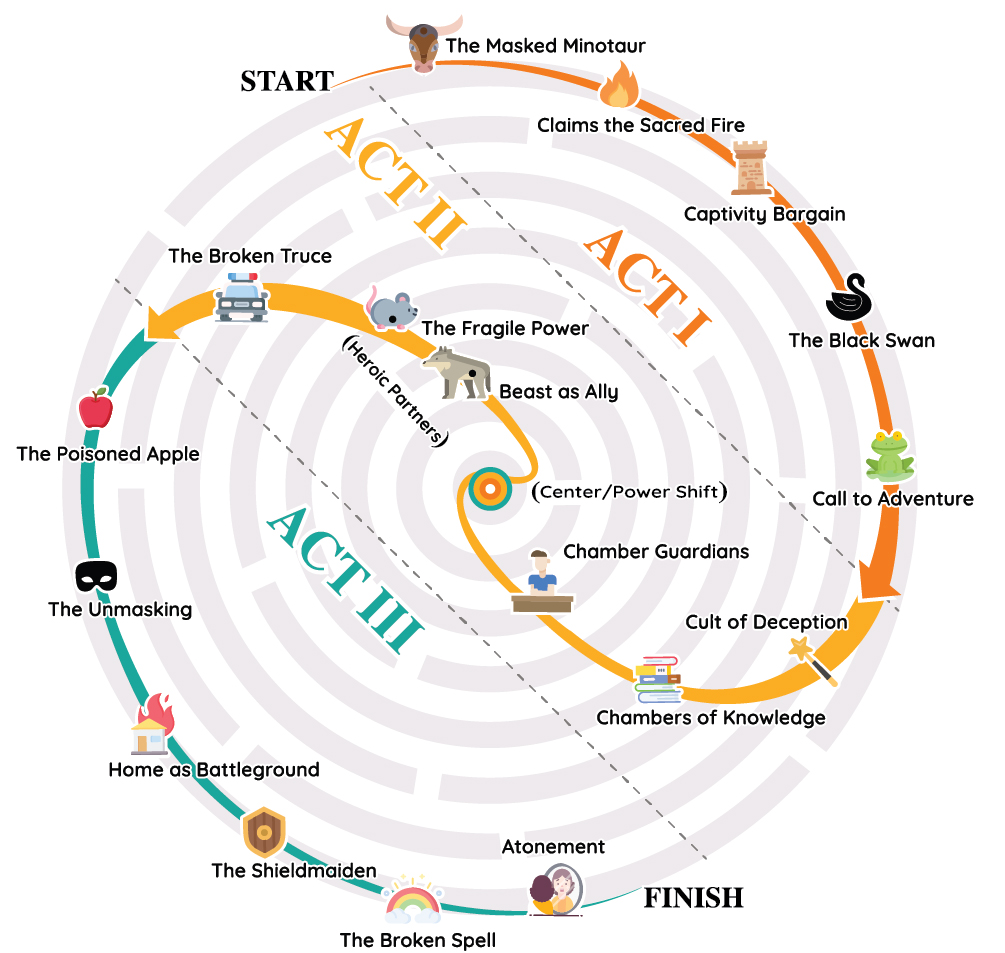

Below is the spiral design of the inward journey. The heroine travels deeper into the native culture before emerging out again. The growth arc features numerous distinctions.

Socio-Cultural Conflicts

The heroine’s labyrinth narrative model liberates itself entirely from the origins of a hunter-warrior story as modeled by mostly male protagonists. Secondly, the labyrinth separates itself even from the universalized hero’s journey, a variation rooted in Campbell’s departure and return. The heroine’s patterns and recurrent archetypes emerge authentically from stories with female protagonists once we affirm the structural uniqueness of the inward journey.

Instead of a departure from the native culture, we see countless heroines oriented to their societies, from which new but familiar conflicts take shape. Many heroine-centric stories also begin in the Ordinary World, as defined by Vogler, but develop a heightened focus on the social enculturation of the female protagonist. Heroines are often introduced to certain rules, gender roles, fixed traditions, superstitions, institutional methodology, social strategies, inherited customs, moral codes, community factions, family expectations, and cultural values. The confinement of the Ordinary World takes on greater significance because heroines didn’t always experience a total “departure” from society. The pressures of conformity within a social sphere did not establish “home” as a comforting place of safe returns. Instead, they lay the groundwork for a sustained conflict between culture and heroine throughout the story.

Hidden Mazes at Home

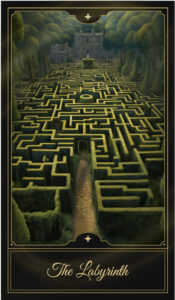

Culture itself becomes labyrinth-like for many heroines in fiction. Under wide-ranging cultural conditions, heroine-centric stories rarely feature a “threshold” beyond the native culture. Inside a labyrinth, a journey of many miles never strays far from the center, so a symbiotic relationship develops between the Ordinary and Special World for the heroine.

Why?

Because the Special World usually surrounds the heroine already. She sees and desires an unfiltered, unrestricted, and unprotected experience of her native culture. The heroine’s identity in the Ordinary World often prevents her from participating in the Special World. The two worlds are closer together in the heroine’s labyrinth–parallel–with the Special World hidden or forbidden. Even stories that appear to be an outward hero’s journeys require a second look. Heroine-centric stories such as Pan’s Labyrinth, Encanto, Alice in Wonderland, Labyrinth, Amélie, and Outlander all represent escapist journeys inside or near the heroine’s home. The events between the Ordinary and Special World are interrelated, and the decisions and consequences in one world affect the other.

In The Wizard of Oz, Coraline, Everything Everywhere All at Once, and Barbie have similar Special Worlds. Each “distant land” is actually a reimagining of the heroine’s home life with exotic doppelgangers of well-known friends, family members, or even themselves. Feelings of yearning, aspiration, and hope sit alongside feelings of frustration, repressed desire, and rebellion. We see the same socio-cultural conflicts in historical stories such as Memoirs of a Geisha, Jane Eyre, or I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. The journey is intimate and inward, familiar but different, yet strangely close to home. For the heroine, the unique relationship between the Ordinary and Special World replaces a linear outward threshold. The narrative experience is often both personal and deeply psychological. Therefore, the labyrinth perfectly symbolizing a full range of multilinear inward journeys–whether fantastical, realistic, or psychological.

Click here to see a six-minute video on the Labyrinth Archetype

Even in well-known short stories such as The Lottery by Shirley Jackson and The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, we see heroines at odds with their native culture. Their dangers are not far off, but nearby or inside the home. A cultural hunter-warrior or universal hero’s journey interpretation doesn’t adequately address the conflicts in heroine-centric stories. Campbell’s hero’s journey sidesteps most socio-cultural conflicts once the hero departs the home sphere. Vogler’s hero’s journey simplifies the Special World as a general shift in conditions. However, the heroine’s labyrinth elevates socio-cultural conflicts as a primary struggle. And so, we behold an alternative cultural figurehead in the heroine, whose growth doesn’t require a departure and return.

Different Journey, Different Villains

Villains, too, are affected by the structural reality of the inward journey. An overwhelming number of heroine-centric stories feature a duplicitous insider from within the native culture. Gone were the monstrous, out-in-the-open militant outsiders like Darth Vader, Thanos, the Kraken, Sauron, and Grendel. Instead of a “Distant Dragon,” heroines often face a dangerous “Masked Minotaur” from within their own native culture.

Heroines often encounter villains who are usually social apex characters. These villains appear pleasing or benevolent but hide a tyrannical side. The disguised or hidden villain brings an entire host of profound archetypal distinctions. These villains can come up close to the heroine, wield social power, and compromise the inner sanctums of society, if not the heroine’s home itself. A Masked Minotaur can also marshal social forces against the heroine. A desire to monopolize or possess the heroine often results in isolation or stigma. A villain disguised in the native culture is distinctive and archetypally profound. And like biblical Esther, the task of unmasking a socially esteemed villain often falls to the heroine.

See below for the heroine’s classic conflict triangle:

Inward Bound

The inward journey is timeless cross-cultural reality with deep archetypal truisms. The presence of distinctive archetypes along an inward journey does not invalidate the outward journey. The hero’s journey will likely remain the standard for an outward journey. However, the heroine’s labyrinth offers a new lens through which to examine and understand our stories.

In psychological, spiritual, and intellectual terms, the inward journey is nothing like the outward journey. Social anxiety, matters of personal identity, one’s role in society, pressure from trusted individuals, the social consequences of various relationships, disguised evils, professional endeavors, and navigating both public and private spheres all generate unique dangers, conflicts, and solutions. As such, the inward journey stands apart. The more we recognize the inward journey as a distinctive arc, the more we appreciate the labyrinth model. The heroine has much to teach us. The heroine’s story is our story; her struggles are our struggles, and her solutions provide a model of growth for all of us.

‘The Heroine’s Labyrinth: Archetypal Designs in Heroine-Led Fiction’ is a new approach to storytelling by author Douglas A. Burton. The writing craft book covers 18 unique archetypal patterns found in heroine-centric stories. Screenwriters, novelists, memoirists, and RPG gamers will all benefit from Burton’ fresh approach to storytelling.

Oct 9, 2020

Many adventure stories, such as ‘The Hobbit,’ use most of the pages moving through liminal space. The main character, Bilbo Baggins, is traveling through exotic settings, far beyond the comforts of home. Liminal space is the “space” between two destinations and as far as the main character is concerned, it is also the space between two different realities.

The most common usage of liminal space is when the heroic figure leaves the safety and protection of their home, and travels toward an unfamiliar and potentially dangerous destination. The heroic figure has left their home behind, and yet they are nowhere, in limbo somewhere. Not all stories are adventure stories, and so liminal space may be a usable theme for a single chapter or even a handful of paragraphs. However, understanding the deeper psychological power of a concept such as liminal space can help a writer spot opportunities to elevate their writing. As a storyteller, you must recognize the significance of liminal space and design a setting that connects to your readers on a primal level and add extra punch to your world and story.

Change begins in liminal space.

Psychologist Carl Jung states, “Individuation begins with a withdrawal from normal modes of socialization, epitomized by the breakdown of the persona.” He calls this withdrawal a “movement through liminal space and time, from disorientation to integration.”

Liminal space typically features four themes:

- Unconsciousness—either fainting, sleeping, or dreaming.

- Transitive setting— physically moving the character between destinations

- Security blanket—an object that symbolizes the familiarity of home.

- Harsh environment— either vast and empty or through a tunnel-like passageway

Most heroic figures, just like you and me, inwardly want to avoid danger. Therefore, our heroines and heroes often “faint” as a defense mechanism when it’s time to face the dangerous and uncertain world. The overtones of disorientation and unconsciousness appear often as our characters enter liminal space. They are infants about to be born. Recognize that. Know that we are looking at our innocent, untested heroic figure and pushing her or him out toward the hazardous world.

Whenever liminal space is portrayed as a vast and empty expanse, like a desert or ocean, it’s to underscore the uncertainty and smallness your heroic figure feels. Whenever liminal space is instead represented by a tunnel-like passageway, it’s to represent a birth canal, the movement away from the safety of the womb.

Liminal space also cues your readers that change has come…is happening now. The heroine or hero is disoriented. They faint or travel through a strange environment and cling to an object that reminds them of home.

Examples of liminal space:

In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy falls into a dream-like state during the tumult of nasty twister. The tornado (a tunnel) lifts her actual home into the sky and away from familiar Kansas. Out of her window, she sees familiar objects and people from Kansas whizzing about, but soon the window reveals the dangerous sight of the Wicked Witch, who tyrannizes the Otherworld ahead. Toto comes with Dorothy and stands in as a familiar reminder of the home she left behind. “Toto, I have a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.”

In Star Wars, Luke Skywalker leaves home for the last time, though he doesn’t know it, to search for the runaway Artoo Detoo. When he encounters the Sand People, Luke immediately faints, which cues viewers that Luke is about to move beyond his familiar world. He soon discovers the death of his uncle and aunt and enters the unpredictable Mos Eisley Spaceport, a place of transit. When he travels aboard the Millennium Falcon, he experiences hyperspace, which is a tunnel of light. “Traveling through hyperspace ain’t like dusting crop, boy!”

In the Matrix, the heroic figure of Neo is flushed through a tunnel and pulled into the “real world” by a giant claw. The imagery is unmistakably themed around the shock of being born. Morpheus soon shows Neo an empty white space called, the Construct, which he describes as “the place in between the neural-interactive simulation of the Matrix.” He even refers to the world as the “desert” of the real. After Morpheus shows Neo the Matrix, the hero falls to the floor and goes unconscious. “He’s gonna pop.”

In the movie Coraline, our young heroine must first fall to sleep and dream before she can cross into the Otherworld. Once asleep, Coraline opens a secret door and must crawl through a mysterious tunnel of cobwebs and dust. All the objects of her home surround her but offer the illusion of a better home. “You know you can stay here forever. There’s just one condition.”

In Wonder Woman, when Diana leaves her home behind, she boards a boat that must cross a vast and empty sea. She brings her gauntlets, shield, and sword with her. Once aboard, Diana lays down and sleeps. Her mother warns her: “You know that if you choose to leave, you may never return.”

Avatar features liminal space both in hypersleep en route to Pandora, which floats through the vastness of space. Jake Sully’s wheelchair, a symbol of his weaker, dependent earthly life comes with him to the distant planet. Jake must also “faint” each time he enters his Avatar body by sleeping in a link pod. Each time, his consciousness travels through a tunnel. “Everything is backwards now, like out there is the true world, and in here is the dream.”

In Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon, the mother of the aristocratic Jen Yu falls unconscious when the bandits attack. Jen then pursues a bandit to retrieve her ivory comb, which is the object that symbolizes her aristocratic home life. Rather quickly, Jen finds herself surrounded by a vast and empty desert. “All this trouble for a comb?”

In Fight Club, the narrator’s home life is cut off when his condo (home) is destroyed by an explosion. Like Coraline, he finds an “opposite” home when he wanders off to the empty “toxic waste part of town” to squat in an abandoned house. He keeps his briefcase, a stark reminder of the shallow corporate life he left behind. The narrator faints all the time due to narcolepsy. He even states, “If you wake up at a different time in a different place, could you wake up as a different person?”

Like any step in the heroic transfiguration, liminal space, too, can be expanded upon in amazing ways. The movie Gravity features a heroic figure who’s trapped in liminal space, haunted by ghosts of familiar astronauts and listening to folksy transmissions from the earth below. She’s even filmed floating in zero gravity in the fetal position at one point, an image that evokes feelings of infancy and smallness when faced with the dangerous world just beyond.

Liminal space is a powerful tool for writers. Take a look at your scenes and see if there’s an opportunity to expand an existing scene using the tools discussed above. Be creative. Design a liminal space that echoes your unique world and captures the primal imagery of human change. Our subconscious minds will recognize your handy work, even if our conscious minds do not.

Douglas A. Burton is an award-winning author who studies the phenomenon of heroic figures in fiction. His critically-acclaimed historical fiction novel, ‘Far Away Bird’ features the origin story of Byzantine Empress Theodora. The writing experience led Doug to outline and propose a narrative monomyth for female-oriented fiction that he calls the heroine’s labyrinth, an alternative to the hero’s journey. To see the stages of the heroine’s labyrinth, click here.

Jun 23, 2020

5 Unexpected Virtues of Role-Playing

Want to spice up the writing room? As writers, we all do pretty much the same things—we read the Elements of Style, brush up on our hero’s journey, try to write every day, and of course, unlock the mysteries of story structure. But have you ever considered setting aside the Chicago Manual of Style and picking up instead the Dungeons & Dragons Core Rulebook?

I know, I know. Our sophisticated writer persona cringes at the thought of teenagers circling a table and talking about half-elves, hit points, and spellcasting. But I can’t stress it enough: role-playing made me a better writer. Period.

Not all role-playing games are fantasy adventures. There is almost certainly a gaming module that matches your preferred genre: science fiction, historical fiction, crime & mystery, Gothic horror, chick lit, spy games, 1980’s urban fantasy…you name it. Role-playing games have evolved to suit every taste and demographic.

Let’s explore five unexpected virtues of role-playing and how they animate the craft of writing in critical ways.

#1 – Diversity of Perspective

If you’ve ever hosted a role-playing game as the revered ‘Dungeon Master,’ you’ll discover that while player characters focus on a single character, you must play all the other roles in the world. That means role-playing people with different genders, personalities, occupations, socio-economic classes, cultures, authority levels, and temperaments. For example, by simply role-playing many women over the years, I experienced the full range of bizarre behavior men exhibit when courting a lady. Unexpectedly, I found myself adjusting my own behavior around women, but more importantly, I also learned to write better female characters. By role-playing so many diverse characters, a writer becomes acutely aware of viewpoints and perspectives that vary greatly from our own.

#2 – Character Development

When you role-play a character that you designed, you naturally take a liking to them. You consider all manner of details regarding their appearance, languages, personality, backstories, gear, and skillsets. To make a character not only capable in their world, but you must also understand their place in the world. This will help writers better understand the relationship every character has with their culture as well as with other people. By building a character and experiencing progress, your inner writer is sharpening crucial skills for great character development. You also develop a natural sense that all action leads to growth. Otherwise, the action loses its meaning.

#3 Improvisation

Once you get over the initial embarrassment of “acting” in front of your friends or even strangers, role-playing delivers real power. Situations change minute by minute. Player characters are all interacting in real-time, and you have to keep up. Witty lines of dialogue or dramatic moments crop up organically. This type of free-flow storytelling and character interaction builds up your writing muscles better than almost any other skill. Your scenes gain that coveted touch of spontaneity that great writing requires. Your imagination auto-populates dialogue, body language, emotion, and interactions at a rapid pace. Scenes flow with authentic precision because the improvisation of role-playing caters toward free-flow experiences inherent to writing.

#4 Conflict

One of the most cryptic aspects of writing is conflict. It takes writers years to learn how to build tension or establish conflict in each chapter. I used to think storytelling was a matter of a logical and, therefore, believable sequence of events. Try being a Dungeon Master. You learn to play off the independent actions of the players while introducing dangers, obstacles, rewards, or incentives and at every turn. Being a good Dungeon Master means keeping player characters engaged, off-balance, misdirected and entertained—exactly what writers must do. Crafting great chapters is akin to hosting a great couple of hours of live gameplay.

#5 Settings

Writers love settings. But only role-playing taught me the real importance of a setting. In a role-playing game, every environment becomes a chessboard for the player characters. I learned never to underestimate the ingenuity of players when it comes to solving problems. Every object and prop, every window and door, every light source and shadow will come into play. More than merely some “backdrop” for characters, a setting reveals a ton about the story, the culture, the values, and the daily mode of operation in your story world. Each setting has a purpose and function in the world, and likewise, each setting brings its own dangers and delights. Role-playing forces you understand the interdependence a setting has on the characters and the story.

Conclusion

These five aspects are just a handful of the benefits writers gain when engaged in role-playing games. Try it out. If you’re a writer, consider hosting an adventure with creative friends or even your kids. Just talking about the genre and setting builds tremendous anticipation and excitement about playing. Choose a compelling world or era. Order a pizza, play music to fit each scene, use pictures, bring props. Whatever brings an imagined world to life will only feed that inner writer in ways that more conventional methods can’t touch. Never forget that play is at the very center of a creative soul.

Douglas A. Burton is a historical fiction author who believes in the transformative power of storytelling. His novel, ‘Far Away Bird,’ which follows the early life of Byzantine Empress Theodora, won multiple awards and garnered critical acclaim. See more at douglasaburton.com.