Welcome to the fifth article in a series that looks at the heroine archetype as a distinctive cultural figurehead in narrative fiction. This article expands on the “heroine’s labyrinth” storytelling model as a serious alternative to Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey. In short, there are many patterns and recurrent themes in heroine-led fiction that deserve a closer look. And although the female-oriented heroine is given credit here, her message is universal and inclusive to all of us.

Click on the video below for an awesome recap of the heroine’s labyrinth:

Here are the story elements of the heroine’s labyrinth that we’ve covered so far:

- Heroine-centric journeys tend to be circular and inward through her native culture, rather than linear and outward away from her native culture.

- Heroines are often tangled in a web of social norms from their native culture.

- Most villains are a duplicitous “minotaur” archetype who are typically members of the heroine’s native culture, rather than a menacing “dragon” archetype from outside the native culture.

- Half man, half beast – the minotaur is often “masked”, showing a publicly generous face, but disguising an oppressive activity.

- Heroines must unmask the minotaur before the final battle.

- The heroine’s final battle does not take place in a faraway place, but usually occurs inside the home (or on home turf that is supposed to be safe).

- The heroine often models behavior for breaking certain gender roles or traditional social norms.

- Heroines often exhibit a “shield-maiden” moment by physically interposing themselves between the unmasked minotaur and a potential victim.

The Beast as Ally

This concept alone triggered the whole idea of the heroine’s labyrinth as a separate storytelling model. While listening to Professor Hannah B. Harvey’s university course, The Art of Storytelling: From Parents to Professionals, Hannah discussed the recurrent mythology of Little Red Riding Hood in terms of fairy tales. The common ingredients are an innocent girl, a masculine beast in disguise, and an attempt by the beast to prey upon the girl. Professor Harvey indicated that Little Red Riding Hood is a universal theme about budding womanhood and a cautionary tale about the choices that lay ahead for a young heroine. While these archetypes and themes are very familiar to all of us, I realized that they don’t appear in the hero’s journey. Is there a storytelling model for heroines that has its own path?

Yes.

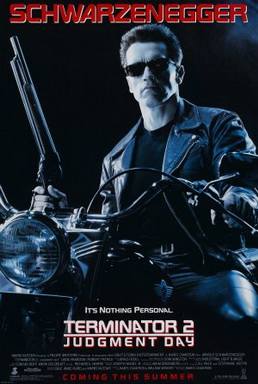

While Professor Harvey is exactly right, I believe there’s more here than budding womanhood alone. If we take a closer look at how the themes in Little Red Riding Hood play out in other tales–from the Dorothy Gale’s Wizard of Oz to Sarah Connor’s Terminator saga to Carol Danver’s Captain Marvel–we’ll see that heroines are modeling deeper wisdom and showing us how to save the world their way.

So, to discuss the phenomenon of the innocent heroine and the dangerous beast, I’d like to spotlight the concept of xenopathy. The Greek word “xeno” means “stranger” or “foreigner,” as in xenophobia. And the Greek word “pathos,” which means “feeling” or “emotion,” as in sympathy or empathy.

The villain in most heroine-centric stories is typically a minotaur archetype. The heroine is justified in fearing the minotaur and in committing herself to defeat this villain. And as discussed in earlier articles, the minotaur is particularly dangerous in that he (or she) is often masked, simultaneously providing material benefit and material oppression.

And yet, while the animal masculine clearly presents a real-world danger to the heroine, there is almost always a second, almost mirror image of the minotaur archetype: the beast archetype. The heroine almost always forms what I call a “xenopathic bond” with the beast archetype. We confront this imagery time and time again, where the heroine loses her fear of the beast and even attempts to understand the beast. She may suspend a negative judgment or question a widely believed stigma about the beast. Her effort to understand someone who is unlike herself often results in inspiring genuine change, specifically in the destructive nature of the beast. The interaction is not always nurturing either. Quite often, the interaction is confrontational and challenging.

The xenopathic bond is an amazing aspect of heroine-led fiction because it represents a new pathway for solutions within her native culture. The heroine models the real-world actions for cooperation between two unlike individuals as well as an alternative to violent conflict. Sometimes, the recruitment of the beast is the key to defeating the minotaur. The beast often chooses to aid or protect the heroine in the quest to defeat the minotaur. Xenopathy sometimes even causes the heroine to turn against her native culture as Katniss Everdeen did in Hunger Games or Furisoa did in Mad Max: Fury Road. And in the most extreme cases, the heroine may even defect from her native culture and join an outside cause as Carol Danvers did in Captain Marvel or both Gamora and Nebula did in the Avengers saga.

Examples of the Beast as Ally Scenarios in Heroine-led Fiction:

Sarah Connor, who had to fight a terminator to the death in the first film, now finds a mirror image of the terminator stepping out from her past nightmares and offering to assist. Although the alliance is shaky at first, Sarah eventually develops the critical xenopathic bond with the terminator and comes to admire the Beast’s reliability and even relentless pursuit of a goal. They team up in a big way to face down the real minotaur, a disguised, or shape-shifting T-1000.

Special Agent Clarice Starling is trying to hunt down the brutal serial killer Buffalo Bill. However, she also recruits the aid of a mirror image serial killer named Hannibal Lecter. He is a true beast archetype who eats his victims like the big bad wolf. And Buffalo Bill, like a wolf in sheep’s clothing, even wears the skins of his victims. Clarice forms a famous xenopathic bond with Hannibal Lecter, who mentors Clarice by revealing the psychology of a serial killer. There’s a suggestion of a romantic bond, but this appears to be a mostly symbolic nod to the unlikely xenopathic bond, which does lead to a life saved.

Natasha Romanov, also known as the “Black Widow,” faces down super villains on a regular basis. But when superhero Bruce Banner loses control, he becomes the ultimate Beast archetype. He’s wild, out of control, violent, and aggressive. But only Natasha has the ability to form that special xenopathic bond with the Incredible Hulk. The rest of the world attempts to subdue the Hulk through violence. So, we should regard the Black Widow’s compassion as wisdom, a pathway to calm the beast non-violently, so that the more gentle Bruce Banner can return.

King Kong has perhaps one of the most famous Beast as Ally motifs. While the entire world views the giant gorilla as a terrifying monster that must be destroyed, heroine Ann Darrow forms a xenopathic bond with Kong, and sees an almost human light in the animal’s eyes. Although Kong is obviously possessive of the heroine, she recognizes that King Kong is also a victim of a human society that is quick to destroy whatever it fears. From the top or the Empire State Building, Ann attempts to defend King Kong from approaching warplanes. I think they are wrong to say that beauty killed the beast. Man killed the beast and beauty tried to save it.

In the Twilight saga, Bella Swan attracts and befriends two beast archetypes, Edward Cullen and Jacob Black. One is a blood-thirsty vampire who must restrain himself, and the other a shape-shifting werewolf. The two “beasts” compete to aid and protect the heroine throughout the story.

Game of Thrones is loaded with the Beast as Ally themes. In fact, almost every single heroine in Game of Thrones forms a xenopathic bond with a member of a foreign culture. And as such, these heroines direct entire plot lines at times by forming alliances between two unlike cultures. These heroines create the potential for peace. One successful example is Ygritte, who forms a xenopathic bond with Jon Snow, who is member of the Crows, the sworn enemy of her native culture. However, her bond with John will eventually put an end to the centuries-old conflict between the Wildlings and the Night’s Watch.

Daenerys Targaryen forges the most famous alliance with Khal Drogo, who is a supreme example of the beast archetype. He becomes one of the most fearsome and unforgettable allies in the series and Daenerys joins his culture, while Drogo pledges himself to her cause. Brienne of Tarth bonds with the notorious Jaime Lannister. Margaery is paired with the villainous and monstrous Joffrey. Arya Stark befriends the murderous Hound through a series of adventures. The most dangerous warrior in the show, the Mountain, is eventually brought into the service of protecting Cersei around the clock. And the healing heroine, Talisa, ends up with Robb Stark. She has true xenopathic dialogue when she tells Robb about her mother’s opinion of the North Men as “stinking barbarians.” But each heroine in Game of Thrones faces the beast archetype and some succeed while others fail to build bridges and forge peace in the world.

A few stories that feature male heroes that feature xenopathic bonds are John Dunbar in Dances with Wolves, Elliot in E.T., and even Bruce Wayne in Batman Begins, who goes out of his way to understand the psychology of the criminal mind. Even Mando, in the new hit series, The Mandalorian, forms xenopathic bond with the adorable baby Yoda and turns against his mercenary culture.

In heroine-led fiction, some of our greatest heroines are modeling heroic behavior that stands on its own. The heroine who faces the beast archetype is establishing much more than merely budding womanhood or expressing a mere attraction to dark masculine forces. She is showing us new pathways, new solutions, and is challenging all of us to rethink old habits, cultural stigmas, or potentially destructive social norms. These recurrent themes are different from the hero’s journey. Heroines are challenging us to look a little closer to home, possibly right in our backyard for modes of change. The wisdom and power of the heroine are truly timeless expressions and universal as well. Regardless of the historical era or degree of freedom, the heroine finds a way to save the world.

And xenopathy, learning to understand someone who is unlike ourselves, is something we can all learn together.

What do you think? Leave a comment below and share your thoughts.

Douglas A. Burton is an award-winning author of ‘Far Away Bird‘, a novel about the historical heroine Empress Theodora. For more, visit douglasaburton.com or you can follow Doug on social media.