Home as Battleground

Welcome to the third installment in a series of articles that explore the heroine archetype as a vital cultural figurehead. This article expands on the heroine’s labyrinth as a heroine-centric alternative to the hero’s journey in both narrative structure and character arc. In the last article, we discussed how heroine-centric stories tend to feature villains who are members of the heroine’s native culture, a hidden minotaur, rather than a distant dragon who threatens the native culture from afar. The heroine’s journey is often circular and inward rather than linear and outward.

As the Coronavirus era rolls on, many of us are quarantined at home, spending extra time with family or enjoying a little extra solitude. Therefore, let us reflect on the meaning and symbolism of ‘home’ in terms of fiction and our favorite heroines. As a matter of story structure, the native culture and the home often play a central role.

In fiction, ‘home’ sometimes represents a place of comfort and safe returns. Remember the power of “home” in The Lord of the Rings? Saving the Shire and returning home motivated Frodo and Sam as they ventured toward Mount Doom. The Bat Cave or Fortress of Solitude are also places where male-oriented heroes return for comfort, healing, and peace. However, for heroines, the meaning of home isn’t always positive. Home may be a symbolic threat to the heroine’s identity and individuality. And yet, in the heroine’s labyrinth, to leave home is to abandon certain responsibilities that will disrupt some kind of cultural order. Leaving home often generates feelings of guilt and moral dilemmas for the heroine.

Because the heroine’s labyrinth often features a villain from within the native culture, the story structure shifts regarding the climactic final showdown. In the hero’s journey, the climax often features a final confrontation of single combat between the hero and the villain in a far-off location, typically on the villain’s turf. However, the heroine’s labyrinth model has a stunning pattern of final showdowns upon familiar grounds, a residential abode or right inside the home itself.

This is no small thing.

Whereas the male-oriented hero suffers from the perils of an exotic setting far from home, the heroine often fights in safe places, whether she’s prepared or not. There, right in the heart of the home, surrounded by the symbols and objects of her own native culture, the heroine goes into battle. Psychologically, this distinction is quite powerful because it underscores the heroine’s lack of safety even within the safest places, even among those she’s supposed to trust. While the heroine’s journey may lead her in circles or dead ends, she often ends up in a battle right where she started.

Home.

This narrative pattern is powerful because the heroine models heroic behavior that teaches us how to confront threats from within. The heroine stands as a timeless archetype who confronts the dark side within ourselves, our families, our institutions, and native culture.

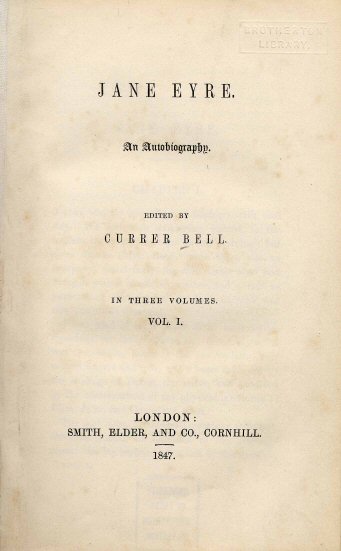

In literature, many of the great heroines fight battles right in the home. Jane Eyre, Elisabeth Bennet, Anna Karenina, Scarlet O’Hara, and Scout Finch all find their native culture to be a battleground. The social norms of the native culture fuel the heroine’s conflict.

Looking at our modern stories, I found countless examples of heroine-centric stories in which the battleground is at home. It’s amazing to see so many examples of this pattern that we may not have noticed before.

The Hunger Games is a classic example of the heroine’s labyrinth. The heroine’ s native culture is Panem’s District 12. Once again, home, family, and friends are not safe. President Snow must be unmasked as the minotaur who hides in plain sight, and Katniss must fight on her native turf, which gives the story its revolutionary overtones. The author, Susan Collins, actually states that she modeled The Hunger Games after the myth of Theseus and the minotaur, in which the native culture sacrifices seven boys and seven girls to the minotaur at the center of the maze.

In Kill Bill, Beatrix Kiddo’s final dual is within a domestic home, where her daughter innocently plays with the minotaur, Bill. The filmmaker, himself, never even shows us the face of the villain, keeping this minotaur masked throughout the entire first film.

Clarice Starling tracks down the masked monster, Buffalo Bill, inside an innocent-looking suburban residence. Notice how the basement turns into a claustrophobic labyrinth as she stalks the minotaur. But ultimately, the heroine’s final showdown is once again inside a house.

Wonder Woman, too, opens her film with classic heroine’s labyrinth dialogue. In a voiceover, she says, “the closer you get, the more you see the great darkness within.” Wonder Woman unmasks Ares, the God of War, who is hidden amongst the “good guys” or “home team” of World War II, the Allied Forces.

Coraline’s quest leads her through many rooms in her home labyrinth until she discovers that her ‘other’ mother is indeed a hidden minotaur whose generosity and favor are a disguise. The battle takes place inside her home.

In Tangled, after navigating the maze of her own native culture, Rapunzel also travels back to where she started…home. There, she unmasks her false mother, Gothel, and the final battle takes place inside her very room.

In The Color Purple, the story is replete with a world of interconnected labyrinths. Home after home has a minotaur within. The oppressor is not far off, but up close, personal, and within the domicile. No place is safe, and battles are often fought…and lost…right inside the home.

Captain Marvel begins in the Kree civilization, which represents her native culture in terms of story. But once again, this is a deception. Her friend and mentor, Yon-Rogg, is unmasked as the hidden minotaur and Carol Danvers must turn against the native culture that she thought raised her.

Dorothy Gale’s entire quest is a fable to teach “there’s no place like home.” Her native culture is dressed up as an exotic land. Oz, after all, is really just a manifestation of the heroine’s humble hometown. The yellow brick road is a labyrinth and she (and Toto) must unmask the great and terrifying Wizard of Oz as an illusory power.

In the provocative film, Ex Machina, Ava is held captive in a high-tech labyrinth. She unmasks the high-profile genius, Nathan, as the minotaur. He is her creator and she must defeat him inside the residential fortress that represents the only world she knows.

In Pan’s Labyrinth, young Ophelia also duels a villain she’s supposed to trust. The movie’s title already evokes the labyrinth, which appears in her figurative backyard. The hidden minotaur is her own stepfather, whom her mother entrusted, and Ophelia’s battle takes place not far from where she lived and slept.

Frozen also features two heroines, who are sisters, Anna and Elsa. Elsa experiences the brunt of the clash between a heroine and her native culture, while Anna must unmask the hidden minotaur, the dashing and duplicitous Prince Hans. The battles are fought at home.

In Inglorious Basterds, Shoshanna unmasks the previously charming Fredrick Zoller as the minotaur before slaying him. Once again, her battlefield is not far off, but inside her own cinema.

In Star Wars the Clone Wars, Ahsoka Tano clashes in the most dramatic fashion with her native culture. Pulling double duty, both the Galactic Republic and the Jedi Order turn against her in full. And when Ahsoka is finally exonerated, she bravely chooses to go her own way, rejecting the moral ascendency of her native culture’s greatest institutions.

Scarlett O’Hara kills one person in Gone with the Wind, a looting Union soldier, whom she slays inside her home.

Home as a place of safety? Hell, home is a hot zone for many heroines. Heroes and heroines don’t always have to travel far away to save the native culture. Sometimes, they fight the native culture in order to free it from within. “Home as Battleground” is only one of many recurrent themes in the heroine’s labyrinth story model. More to come in the following weeks.

Douglas A. Burton is an award-winning author of the historical fiction novel, ‘Far Away Bird.’ He came upon the heroine’s labyrinth while writing about one woman’s journey, Empress Theodora of Byzantium. The author realized that certain aspects of the hero’s journey didn’t always apply to his heroine. He believes that heroines represent a powerful cultural figurehead that deserves greater attention. Follow him on Facebook to stay updated

Wow, Douglas. As I was reading this, I was led to read the Heroine’s Labyrinth page on your site. I have just finished reading through each of the points along the Heroine’s Labyrinth and as I was going along it was like this voice in my head was narrating my own life’s story through each of the points! I have LIVED this. And although I have attempted to parallel my own life with the steps on the Hero’s Journey, during the Heroine’s Labyrinth I felt these deep body zings with practically every step along the way. It was hard to keep myself from blurting out (over and over), “YES, I have lived exactly this moment!”. Wow. Thank you for outlining this. I feel like there is much for every heroine out there to gain from this understanding, myself included. Thank you for bringing clarity to that sense that I’ve been constantly “doing it wrong”, which simply stems from the step of leaving behind the cultural expectations as I enter the labyrinth. No, I am doing it exactly right, I am following the Heroine’s Labyrinth! THANK you for helping me to know myself better.

What was one of the most surprising things you learned in creating your books? I think my biggest discovery was the cultural significance of a heroine-centric story. I grew up studying Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey and based a ton of work on story structure and character development on it. However, I came to find many differences in the narrative arc when it came to Theodora that I decided to study female-driven stories and films. I came up with something I’m calling the ‘Heroine’s Labyrinth,’ which is a heroine-centric model for story structure that I’m damn excited about! Many women encounter a host of different challenges in our cultural stories and in many cases, model a different kind of heroic behavior. Generally speaking, heroines save the world in different ways. Whereas male-oriented heroes taught me how to leave home and prove my worth, female-oriented heroes taught me how to overcome social roles and unmask villains here in my own native culture. I’m inspired by heroic women more than ever before and plan to pursue this study long into the future. I think I’m on to something.