Sep 7, 2020

The premise of Mulan was ripe to make a bold statement about heroic women and cultural norms. Instead, Disney just made a movie and missed a major opportunity to deliver a powerful heroine. I care deeply about the portrayal of heroic women in fiction and the art of storytelling. And through that lens, Mulan 2020 falls short because the film’s attitude toward heroic women stays clouded.

Mixed Message #1 – Female Individuality is Subordinate

Mulan is the perfect character to teach us about the importance of individual risk and aspirations in relation to culture and social norms. However, in Mulan 2020, the heroine’s journey merely appears to support Mulan’s individual goal. By the end of the film, family approval and cultural duty swallow up Mulan’s individuation. It’s a total clash. Mulan must subordinate herself to the judgment of her family’s patriarch. Her reward? Mulan gets to serve the emperor! Our heroine eventually submits to the very family values and social codes in which she fought against to break free. According to Mulan 2020, female individuation must eventually answer to the cultural powers that do not change their minds in this film about the role of women in society. They simply make an exception for her.

Mixed Message #2 – Female Ability Comes from Magic

In Mulan 2020, feminine excellence is the result of a random surplus of “chi,” which is an inner force. This internal force is apparently wasted on Mulan since women can’t be warriors, and so she must hide her chi and conform to society. Why is this film afraid to show Mulan attaining great ability as a consequence of hard work, discipline, and practice—you know, three dimensions that apply to real life and real women? Why does Mulan 2020 suggest that inner magic is mostly responsible for Mulan’s heroic actions and abilities? When she leaps over armies and gallops through an avalanche, we aren’t seeing the results of her human potential unmasked—no, we’re merely spectating magical abilities. Mulan should show us that women who don’t prefer traditional gender roles can get the job done if given the opportunity. The movie should have demonstrated that there are Mulans all around us—that having a society that allows individuals to choose their path is better than one that has a path imposed upon them.

Mixed Message #3 – Gender Roles Remain

Mulan is a young woman who can save her native culture from an outside threat. However, her society isn’t looking for her and worse, even if they found her and knew of Mulan’s skills—society would still reject her. Here we see a non-western civilization with its own oppressive gender roles. We meet Mulan, who will bring dishonor to her family and abandon domestic duties if she challenges gender roles. The film sets up the problem wonderfully. However, the film doesn’t follow through. In the end, Mulan’s heroic actions do not bring about any long-term change. She earns the begrudging approval of a few key influencers. Mulan herself makes very few comments about her plight and remains rather quiet overall. While the character of Mulan hides from the Chinese Imperial Army, I feel like the script tries to hide her from modern-day Chinese censors.

And finally, in terms of modeling heroic behavior for young girls (and boys), I guess the message is: pray that you have more chi than everyone else. If not, then you’d better be prepared to conform to traditional gender roles. “Knowing your place” remains the source of honor for women by the end of the movie.

Mixed Message #4 – The Reality of Hidden Identity

The film couldn’t pick between serious drama and magical fantasy and so, the matter of hidden identity was mishandled. I mean, what’s it really like? Mulan 2020 is a live-action film about a woman who must hide from her entire culture in order to save it. A disguise that works flawlessly in a cartoon must now be convincing in live-action. Real men in a real male-only army camp surround her. The film should have aimed higher in exploring the difficulties of a woman passing as a man. In truth, Mulan looked like a woman in disguise through most of the film. In one scene, she merely wanders off to secretly bath at night. But “real” army camps have pitched guard posts, vigilant patrols, and strict time-tables to catch deserters or spies. Soldiers would question a warrior that routinely skips bathing. If you’re going to do live-action, you must solve for these realities, which could have intensified all the tension and touched on real-world issues—instead, the live-action works against the film.

Mixed Message #5 – No Fun

In the end, Mulan 2020 just isn’t very fun. Was this supposed to be a fun film for kids? Who was the target audience? The somber overtones of duty and honor hung like a cloud over the movie. And the removal of beloved characters, like Mushu, left the film feeling vacant and without any heart. Instead, the film replaced Mushu with a symbolic phoenix (not a character) that has no speaking lines. All the charm and splash of the animated Mulan is completely missing in this film. It’s just too serious.

Mulan 2020 had a beautiful opportunity to make a bold statement about a heroine who forced society to confront its limited view of women in general and gender roles in particular. The timing for such a film was perfect. The audience was ready. The filmmakers, surprisingly, were not.

Douglas A. Burton is an award-winning historical fiction author who cares deeply about popular depictions of heroic men and women. His ongoing work on heroic women in fiction centers on the mythology and recurrent themes of heroine-centric stories. He believes that the heroine’s labyrinth model is a serious alternative to the male-oriented hero’s journey. For more, visit douglasaburton.com.

May 20, 2020

Welcome to the fourth installment in a series of articles that looks at the heroine archetype and the recurrent themes found within heroine-centric stories. This article expands on the heroine’s labyrinth for narrative story structure as an alternative to the hero’s journey. Here are the story elements of the heroine’s labyrinth that we’ve covered in previous articles:

- Heroines often struggle against the social rules of their native culture.

- Villains follow the “minotaur” archetype, who are usually members of the heroine’s native culture.

- The minotaur is “masked,” hidden, or disguised, appearing half-benevolent, half oppressive.

- Heroines must first unmask the minotaur before the final battle.

- The heroine’s final battle is not far off, but often inside the home (or on home turf).

- The heroine often provides a model for breaking with certain gender roles or social norms.

- Heroine-centric journeys tend to be circular and inward, rather than linear and outward.

This week, I want to discuss one of the most heroic aspects in all fiction, the Shield-Maiden Moment. Structurally, the shield-maiden moment occurs in the third act, right before the final confrontation with the villain. However, it can occur earlier as an emergence moment for the heroine as well. This is a moment where the heroine physically interposes herself in between the minotaur and a defenseless life, typically just a few feet away.

Symbolically, the heroine becomes a human shield against the forces of violence and destruction. She holds her ground and stands face-to-face against brute power as the ultimate and sometimes unexpected first responder. This is a special dynamic for combat in fiction because it carries a dual role. The heroine must not only defeat the fearsome minotaur, who is a serious physical threat, but she must also save another potential victim. The heroine is not acting in the manner of self-sacrifice, although it may appear that way—because her mission cannot allow her to fail. If she’s defeated, not only is she captured or destroyed, but the life she defends will also be captured or destroyed.

How does this contrast with the hero’s journey?

In the hero’s journey, the male-oriented hero typically confronts a menacing “dragon,” who typically comes from outside the native culture. The dragon is exotic, dangerous, and threatens the native culture with destruction or oppression. The hero eventually faces the dragon in single combat. The meaning of the combat is typically a test of worthiness for the hero, with the dark archetype of evil on one side and the light archetype of good on the other. It’s powerful imagery that recurs with serious regularity. Whether it’s Luke Skywalker facing Darth Vader on Bespin, Neo staring down Agent Smith inside the Matrix, or Captain America versus Red Skull in Nazi Germany, the basic design is the same. The hero has undergone their trials and must test their mettle against a villain who doesn’t lose. Like two rams about to rise and smash heads, this recurrent theme tells readers or viewers that we are in the final stages of a story and that the conflict will be resolved in this battle.

For the heroine’s labyrinth, facing a villain while also protecting life is an amazing contrast and perhaps, the most heroic moment in fiction. The Shield-Maiden moment happens whether the heroine has training or not, whether she is prepared or not. And quite often, the minotaur cheats to secure victory. All forms of power and deception are brought to bear upon the heroine, and yet she prevails. She accomplishes her dual mission—to defeat the minotaur in combat and to protect a living being in close proximity. Truly inspiring. Examples of the Shield-Maiden Moment are everywhere. Here are just a few:

In Aliens, Ripley famously marches up to battle the Queen alien in dramatic fashion. She’s facing a monster that has an overwhelming physical advantage. Her famous line, “Get away from her you bitch” almost perfectly captures the heroine’s stunning willingness to face insurmountable odds when her Shield Maiden Moment arrives.

In The Silence of the Lambs, heroine Clarice Starling confronts serial killer Buffalo Bill with defenseless Catherine Martin trapped in well right behind her.

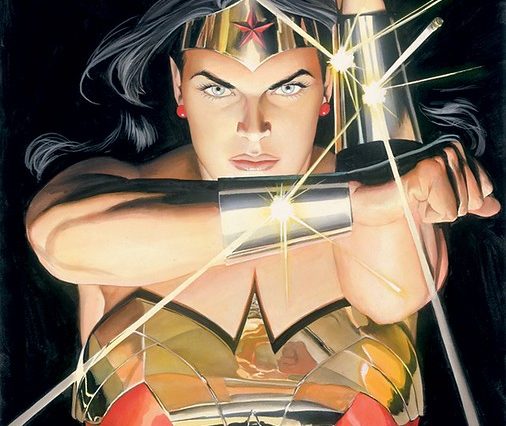

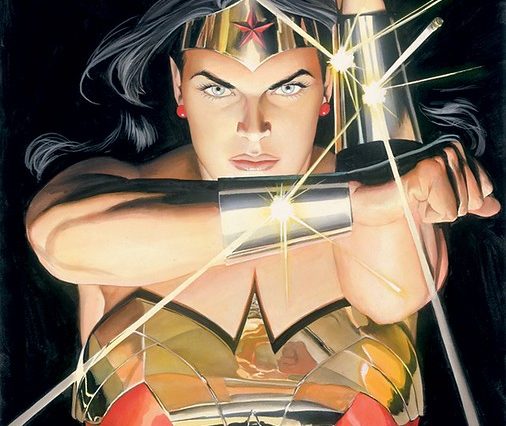

Perhaps one of the most striking examples of the Shield Maiden Moment is in Wonder Woman. Who can ever forget the images of Wonder Woman striding across No-Man’s Land, and then holding up an actual shield while enduring a storm of machine-gun fire, her legs buckling under the strain? She leads the way while the vulnerable Allied infantry mounts a charge across the deadly landscape. Even in the final battle, when Wonder Woman fights the God of War—she must enter battle with Steve Trevor, her love interest, sharing the battlefield with her.

In Moana, the heroic Maui is wounded and without his weapon in the final moments of the battle. He is seconds from destruction as Te Ka rears back for a fatal blow. But, in one of my favorite Shield-Maiden moments, Moana boldly reveals herself by holding up the heart stone to momentarily stop Te Ka. Moana not only makes a stand but goes on to walk bravely up to the villain and heal Te Ka’s heart. This restores the feminine spirit of the world, thus saving it.

In The Terminator, Sarah Connor, who is a server at a diner, fights and defeats an actual terminator while dragging and protecting a defenseless Kyle Reese. Then again, in Terminator 2, Sarah faces down a nearly invincible T-1000 with her son, a young John Connor, standing right behind her.

In Avengers: Infinity War, Scarlet Witch boldly stands against Thanos, summoning a shield of red magic as the overpowering villain closes in. Behind her, a weakened Vision lays on the ground, unable to defend himself.

Brienne of Tarth from Game of Thrones is the ultimate shield maiden. Nearly all her combat involves the valiant protection of life, from Caitlyn Stark to Jaime Lannister. Time and time again, Brienne steps in front of dangerous men as a bodyguard and prevails.

In Avatar, Neytiri takes down Colonel Quaritch in the final battle, while the small human form of Jake Sully, who is physically paralyzed and suffocating, lays in his avatar pod behind her.

In Tangled, Rapunzel duels against her false mother with Flynn Rider laying wounded on the ground at ger back. Again, the heroine’s battlefield is crowded with others.

In The Lord of the Rings, it is Aowyn who steps in front of the Witch-King when King Théoden falls in battle. When the Nazgul declares that “no man can kill me,” she famously responds, “I am no man.” She then destroys the Nazgul while sustaining terrible injuries.

In Kill Bill, Beatrix Kiddo enters combat against Bill while her daughter, whose existence was just revealed to her, stands in the room just a few feet away.

In The Fifth Element, Leloo, herself, is physically the ‘element’ that will shield the earth from a giant ball of black fire. And her powerful mantra is “protect life.” How fitting.

In Ex Machina, the android heroine, Eva, turns and faces Nathan, the minotaur in the center of the labyrinth. Behind her is another captive android woman. Once again, Eva, herself, becomes a physical shield as Nathan smashes Eva’s limbs. Nathan is defeated and Eva escapes the labyrinth.

When the hidden minotaur strikes in Jane Eyre, it is Jane who steps in and saves a defenseless Mr. Rochester during the blazing fire.

Even in The Force Awakens, Rey fights Kylo Ren with a wounded and defenseless Finn laying in the snow behind her.

The next time you’re in danger, hopefully, there’s a heroine nearby.

For a more in-depth look at all the steps in the heroine’s labyrinth, click here.

Douglas A. Burton’s award-winning debut novel, Far Away Bird, applied the heroine’s labyrinth story model to one of history’s most influential women, Empress Theodora. Far Away Bird is available in paperback on Amazon and audiobook on Audible.com.

Here are the prior articles:

Apr 14, 2020

Home as Battleground

Welcome to the third installment in a series of articles that explore the heroine archetype as a vital cultural figurehead. This article expands on the heroine’s labyrinth as a heroine-centric alternative to the hero’s journey in both narrative structure and character arc. In the last article, we discussed how heroine-centric stories tend to feature villains who are members of the heroine’s native culture, a hidden minotaur, rather than a distant dragon who threatens the native culture from afar. The heroine’s journey is often circular and inward rather than linear and outward.

As the Coronavirus era rolls on, many of us are quarantined at home, spending extra time with family or enjoying a little extra solitude. Therefore, let us reflect on the meaning and symbolism of ‘home’ in terms of fiction and our favorite heroines. As a matter of story structure, the native culture and the home often play a central role.

In fiction, ‘home’ sometimes represents a place of comfort and safe returns. Remember the power of “home” in The Lord of the Rings? Saving the Shire and returning home motivated Frodo and Sam as they ventured toward Mount Doom. The Bat Cave or Fortress of Solitude are also places where male-oriented heroes return for comfort, healing, and peace. However, for heroines, the meaning of home isn’t always positive. Home may be a symbolic threat to the heroine’s identity and individuality. And yet, in the heroine’s labyrinth, to leave home is to abandon certain responsibilities that will disrupt some kind of cultural order. Leaving home often generates feelings of guilt and moral dilemmas for the heroine.

Because the heroine’s labyrinth often features a villain from within the native culture, the story structure shifts regarding the climactic final showdown. In the hero’s journey, the climax often features a final confrontation of single combat between the hero and the villain in a far-off location, typically on the villain’s turf. However, the heroine’s labyrinth model has a stunning pattern of final showdowns upon familiar grounds, a residential abode or right inside the home itself.

This is no small thing.

Whereas the male-oriented hero suffers from the perils of an exotic setting far from home, the heroine often fights in safe places, whether she’s prepared or not. There, right in the heart of the home, surrounded by the symbols and objects of her own native culture, the heroine goes into battle. Psychologically, this distinction is quite powerful because it underscores the heroine’s lack of safety even within the safest places, even among those she’s supposed to trust. While the heroine’s journey may lead her in circles or dead ends, she often ends up in a battle right where she started.

Home.

This narrative pattern is powerful because the heroine models heroic behavior that teaches us how to confront threats from within. The heroine stands as a timeless archetype who confronts the dark side within ourselves, our families, our institutions, and native culture.

In literature, many of the great heroines fight battles right in the home. Jane Eyre, Elisabeth Bennet, Anna Karenina, Scarlet O’Hara, and Scout Finch all find their native culture to be a battleground. The social norms of the native culture fuel the heroine’s conflict.

Looking at our modern stories, I found countless examples of heroine-centric stories in which the battleground is at home. It’s amazing to see so many examples of this pattern that we may not have noticed before.

The Hunger Games is a classic example of the heroine’s labyrinth. The heroine’ s native culture is Panem’s District 12. Once again, home, family, and friends are not safe. President Snow must be unmasked as the minotaur who hides in plain sight, and Katniss must fight on her native turf, which gives the story its revolutionary overtones. The author, Susan Collins, actually states that she modeled The Hunger Games after the myth of Theseus and the minotaur, in which the native culture sacrifices seven boys and seven girls to the minotaur at the center of the maze.

In Kill Bill, Beatrix Kiddo’s final dual is within a domestic home, where her daughter innocently plays with the minotaur, Bill. The filmmaker, himself, never even shows us the face of the villain, keeping this minotaur masked throughout the entire first film.

Clarice Starling tracks down the masked monster, Buffalo Bill, inside an innocent-looking suburban residence. Notice how the basement turns into a claustrophobic labyrinth as she stalks the minotaur. But ultimately, the heroine’s final showdown is once again inside a house.

Wonder Woman, too, opens her film with classic heroine’s labyrinth dialogue. In a voiceover, she says, “the closer you get, the more you see the great darkness within.” Wonder Woman unmasks Ares, the God of War, who is hidden amongst the “good guys” or “home team” of World War II, the Allied Forces.

Coraline’s quest leads her through many rooms in her home labyrinth until she discovers that her ‘other’ mother is indeed a hidden minotaur whose generosity and favor are a disguise. The battle takes place inside her home.

In Tangled, after navigating the maze of her own native culture, Rapunzel also travels back to where she started…home. There, she unmasks her false mother, Gothel, and the final battle takes place inside her very room.

In The Color Purple, the story is replete with a world of interconnected labyrinths. Home after home has a minotaur within. The oppressor is not far off, but up close, personal, and within the domicile. No place is safe, and battles are often fought…and lost…right inside the home.

Captain Marvel begins in the Kree civilization, which represents her native culture in terms of story. But once again, this is a deception. Her friend and mentor, Yon-Rogg, is unmasked as the hidden minotaur and Carol Danvers must turn against the native culture that she thought raised her.

Dorothy Gale’s entire quest is a fable to teach “there’s no place like home.” Her native culture is dressed up as an exotic land. Oz, after all, is really just a manifestation of the heroine’s humble hometown. The yellow brick road is a labyrinth and she (and Toto) must unmask the great and terrifying Wizard of Oz as an illusory power.

In the provocative film, Ex Machina, Ava is held captive in a high-tech labyrinth. She unmasks the high-profile genius, Nathan, as the minotaur. He is her creator and she must defeat him inside the residential fortress that represents the only world she knows.

In Pan’s Labyrinth, young Ophelia also duels a villain she’s supposed to trust. The movie’s title already evokes the labyrinth, which appears in her figurative backyard. The hidden minotaur is her own stepfather, whom her mother entrusted, and Ophelia’s battle takes place not far from where she lived and slept.

Frozen also features two heroines, who are sisters, Anna and Elsa. Elsa experiences the brunt of the clash between a heroine and her native culture, while Anna must unmask the hidden minotaur, the dashing and duplicitous Prince Hans. The battles are fought at home.

In Inglorious Basterds, Shoshanna unmasks the previously charming Fredrick Zoller as the minotaur before slaying him. Once again, her battlefield is not far off, but inside her own cinema.

In Star Wars the Clone Wars, Ahsoka Tano clashes in the most dramatic fashion with her native culture. Pulling double duty, both the Galactic Republic and the Jedi Order turn against her in full. And when Ahsoka is finally exonerated, she bravely chooses to go her own way, rejecting the moral ascendency of her native culture’s greatest institutions.

Scarlett O’Hara kills one person in Gone with the Wind, a looting Union soldier, whom she slays inside her home.

Home as a place of safety? Hell, home is a hot zone for many heroines. Heroes and heroines don’t always have to travel far away to save the native culture. Sometimes, they fight the native culture in order to free it from within. “Home as Battleground” is only one of many recurrent themes in the heroine’s labyrinth story model. More to come in the following weeks.

Douglas A. Burton is an award-winning author of the historical fiction novel, ‘Far Away Bird.’ He came upon the heroine’s labyrinth while writing about one woman’s journey, Empress Theodora of Byzantium. The author realized that certain aspects of the hero’s journey didn’t always apply to his heroine. He believes that heroines represent a powerful cultural figurehead that deserves greater attention. Follow him on Facebook to stay updated

Feb 26, 2020

WATCH FULL VIDEO OF THIS BLOG (YouTube)

Ahsoka Tano is one of the greatest Star Wars characters of all time and she’s featured in the most egalitarian Star Wars shows out there, The Clone Wars.

When it comes to the Star Wars universe, the role of heroic women is ever-shifting and in some ways a bit shaky. The original trilogy gave us Princess Leia; the prequels gave is Padme Amidala; the new trilogy put Rey out there, and Rogue One dropped in with Gyn Erso. While all four heroines are arguably iconic in their roles and some are popular, each one has some fair criticism. Princess Leia was never given a central role. Padme was given the dialogue of a cardboard cutout. Gyn gets lost in the crowd. And Rey will be forever haunted by the ghost of Mary Sue.

I say, “Enough negativity!” Let’s talk about the Star Wars heroine who works and, in my opinion, stands among the best of all the Star Wars characters.

You may not have heard of her, but I’m talking about Ahsoka Tano.

Ahsoka Tano hails from the Star Wars animated TV series, The Clone Wars, which has been a buried gem of the Star Wars franchise since 2008. Disguised as a children’s cartoon, the Clone Wars quietly built up a following through sheer force of excellence in writing, animation, voice acting, characters, and storytelling. On Rotten Tomatoes, the Clone Wars is up there with the only the Original Trilogy and at least for now, Disney’s hit series, The Mandalorian. Boasting a level of animation that may never be surpassed on television, The Clone Wars went on to become a multi-award award-winning series, collecting a treasure trove of animation and voice acting awards.

It’s time you discovered it too.

But the Clone Wars series is more than just Star Wars show that “adds” in a few female characters for good measure. Amazingly, they manage this powerful and positive balance without the intrusion of identity politics. Messaging gives way to story. Without a lot of fanfare, the Clone Wars achieves the most egalitarian balance of any Star Wars story. Period.

Women are everywhere in the Clone Wars. The galaxy is embroiled in an epic conflict and women are out in front, leading armies and commanding with confidence. They, themselves, are so comfortable in their leadership roles that you, the viewer, will barely notice or care much about gender and stay focused on what the characters are doing and saying. Women spearhead politics and moral debate. Several planets feature a woman as the leader and cultural figurehead. They inspire uprisings, lead from the front, and make mistakes.

We see plenty of female Jedi, but we also find them in the ranks of the Dark Side. Assaj Ventress in an absolute score for Star Wars villains, a Sith and assassin who hold her own in every episode she’s in. Women are mentors and pupils. They’re good and evil. They’re asserting their presence in the galaxy across the board, true allies and equals of their male counterparts. Without attempting to draw any attention to the incredible representation of women, the Clone Wars is effortless in its egalitarianism. The Clone Wars just lets their characters be themselves.

I’ve studied Ahsoka Tano in-depth and she holds up across every front. She’s heroic. She’s a woman of action. She’s compassionate. She fails time and time again, and I for one, have come to truly admire her as a full character, as rich and dynamic as Luke Skywalker.

I became a genuine fan by episode 19. In one of the Clone Wars’ best episodes, Storm Over Ryloth, Ahsoka Tano is given her first command of a fighter squadron. She’s to lead her clones in an attack on Separatist blockade that is under the command of a fully capable and even cunning Separatist admiral. The animation is up to the task and the action squarely within the Star Wars tradition.

Without her squadron around to defend the fleet, the Republic battleships crumble under a wave of vicious attacks. Ahsoka finally turns back, but not after losing a couple of the clones. And let me say, the clones are all personalized in this show. They have nicknames and personalities of their own. Ahsoka is horrified by the deaths her decision brought and her total failure. As a guy, I never once felt like I was watching a weak girl who didn’t belong on a battlefield meant for men. No, I saw a warrior who took her first loss and swallowed that bitter pill of real consequence. It’s summed up when Anakin, who’s an excellent and compassionate mentor, tells her that losing men is the “reality of command.”

Later in the episode, Ahsoka is again put in charge, but this time of the whole battleship. Her confidence is low. The clone officers openly doubt her, preferring the certitude and experience of Anakin. Ahsoka, herself, has doubts about her ability to lead, especially after such a devastating failure only hours ago. But Ahsoka makes a stand. She devises a brilliant but risky tactical plan and the clone army follows her lead. She carries out the plan herself. The maneuver is successful, and she ends up smashing the blockade and rescuing Anakin Skywalker. Ahsoka overcame her clear failure and endeared me to her character from then on.

Time and time again, we watched as Ahsoka faced real tests and hardships. As the new seasons came out, it became clear that Ahsoka Tano was fast becoming a Star Wars darling. She played her role as Anakin’s padawan to perfection, showing the proper respect to her mentor while daring to challenge him with regularity. She has a mind of her own, even within the military chain of command.

In what I regard as some of the greatest Star Wars there is…up there with the original trilogies—Clone Wars Season 5 concludes with a four-part series that does more to drive home the conflicts and themes of the prequels than even the movies, in my opinion. The democratic institutions are failing. The moral leadership is failing. The military presence is growing. In a bold plotline that foreshadows the events of Revenge of the Sith, Ahsoka Tano is framed for a crime she didn’t commit.

I’ve studied the recurrent themes of heroine-centric stories. And in the epic tradition of the heroine’s labyrinth story model, Ahsoka experiences what’s called ‘the broken truce,’ where the native culture itself turns against our heroine in dramatic fashion. We get our first glimpse of a ubiquitous military that flexing some muscle on the Jedi and the whiff of military dictatorship on the horizon. Admiral Tarkin personally leads the attack on Ahsoka and a conflict arises between Jedi Knight Anakin Skywalker and the galactic military, who are bent on her capturing his fugitive padawan.

Incredible drama ensues with the highest quality visuals. Ahsoka is hunted down by a ruthless dragnet of clones and surveillance. The clones who pursue her are the same ones who Ahsoka had led into battle time and time again for five seasons. They don’t care that she was their former commander. They see only an enemy of the state. The writers and animators have full command over the entire palette of Star Wars sounds and images.

Eventually, she is captured, where she is expelled from the Jedi Order. This represents a total failure of leadership and the Jedi abandon one of their finest and turn Ahsoka over to military jurisdiction. Fans are treated to a courtroom drama of high crimes and treason against the Republic, spearheaded by the defending counsel, Padme Amidala and the military prosecutor, Admiral Tarkin, the future Grand Moff. This is a brilliant use of existing characters, who burst to life in a conflict we all care about.

After Ahsoka is finally exonerated, she does something that stands tall in the Star Wars Universe. The Jedi Order apologizes for doubting her and welcome her back into the Order. Anakin is sorry. They’re all sorry. But Ahsoka Tano turns them down flat. A woman with her own thoughts and moral compass, Ahsoka refuses. She walks away from the Jedi Order leaving the entire leadership of Jedi Masters standing wordless in the vacuum of her departure, the Jedi Order is silently judged as “guilty,” never to recover their moral ascendency again. Anakin Skywalker chases her down and pleads with her to reconsider. The dialogue is perfect, the cinematography is stunning, as fine as any movie.

Ahsoka Tano walks away leaving Anakin Skywalker on the steps of the Jedi Temple. It’s the last time these two see each other as friends. They take two very different paths in the wake of a collapsing galactic order.

What happens next?

No one knows because Disney bought LucasFilm and scrapped the Clone Wars under massive protests. Disney’s new TV show, ‘Rebels,’ came out instead. Yet, after a so-so reception for the new series, the writers of the Clone Wars came in and quickly reintroduced Ahsoka Tano. In an episode that features Darth Vader, voiced by James Earl Jones, himself, the dark lord and his former apprentice from the Clone Wars are thrown back in the mix together. Ahsoka senses the hate and anger and even passes out when she learns that the powerful darkness is her former master, Anakin Skywalker.

The two come face-to-face in a showdown that carries the kind of gravity we’ve only seen in the original trilogy. During the confrontation, Ahsoka strikes a blow to Darth Vader, and for a second, fans see the human eye of Anakin Skywalker through the shattered black mask. We even hear Anakin’s once compassionate voice when utters Ahsoka’s name. We see a glimpse of his humanity. The films never showed us Darth Vader like this until after he turned back to the good side. Ahsoka Tano brings this out of him.

Folks, she’s one of the greatest Star Wars characters of all time in my view. These are incredible storylines and character arcs.

All the criticisms that follow the Star Wars heroines of the big screen are absent here. And now, after all these years of silence, Season 7 of The Clone Wars has finally returned to conclude the saga. The newest episodes are available on Disney Plus and I wanted you to know what the hype was all about.

This is a story about the fall of the Republic, the emergence of the dark side, and the rise of a lone heroine who stands tall among the Pantheon of Star Wars greats. If you love heroic women in fiction and Star Wars like I do, then The Clone Wars is for you.

I highly recommend.

Dec 23, 2019

Two years ago, I thought episode 9 was doomed after the mind-boggling structural flaws in The Last Jedi. Episode 9 had to overcome the absence of an actual villain, the mischaracterization and death of Luke Skywalker, the sad loss of Carrie Fisher, the Mary Sue factor for Rey, and the new reality of “hyperspace ramming,” which made space battles obsolete. In addition to a major course correction, The Rise of Skywalker also had to conclude the new trilogy that started in 2015 and the entire Star Wars saga that began in 1977. And to that end, the movie somehow found a path through the asteroid field. While The Rise of Skywalker has its flaws—and there are many—the movie mostly succeeds in concluding the saga while restoring the Star Wars Universe. The film was likable, funny, light-hearted, dark, emotional, and most importantly of all, it felt like Star Wars. Some fans won’t like The Rise of Skywalker, but the real damage was done in The Last Jedi. I think time and history will bear that out.

Now I confess, I’m among the powerful fan corps that did not like The Last Jedi. While I never once felt the need to ridicule someone who held a different opinion, I stand strongly behind the position that Rian Johnson made significant mistakes in episode 8. In addition, I followed the news and leaks leading up to the release of The Rise of Skywalker, and they weren’t good. So, when I sat down to watch episode 9 on Thursday, I fully expected to be disappointed. And for an opening night Star Wars crowd, the mood was uncharacteristically quiet. When the lights dimmed, when the opening logos and titles appeared, no one bothered to cheer.

“Let’s get this over with” seemed to be the sentiment.

A boring opening scroll wasn’t a promising start. The film wasted time trying to explain Snoke while simultaneously establishing a new villain for the heroine to confront. Then the next fifteen minutes included scenes edited and spliced together in such a rushed way that I shook my head. Not good.

But the film eventually settled down and at some point, I’m not sure when, I started to enjoy The Rise of Skywalker. The mood in the theater shifted too. Clapping and fist-pumps trickled in. I began to wonder…was an epic comeback possible? Last I checked, the home team was getting blown out but the deficit was steadily shrinking. Slowly, surely, you sensed the comeback happening. Like a rainy, muddy football game, the comeback included missed opportunities, setbacks, and a fumble or two. But late in the saga, with the game on the line, J.J. Abrams and company plunged exhaustedly into the endzone as time expired. That’s what you have with The Rise of Skywalker. A sloppy mess of a game where the home team won.

All that said, The Rise of Skywalker isn’t a complete success. The movie has many undeniable flaws, most of which are outgrowths of The Last Jedi. I’ll share what I think worked and didn’t work briefly below. WARNING! SPOILERS AHEAD!

Top 5 Flaws

The Guise of Skywalker

Perhaps the greatest problem I had with the Rise of Skywalker is the misleading title. By killing Luke, the final film didn’t have any living Skywalkers, an odd problem for the so-called Skywalker saga. Rey simply taking the name ‘Skywalker’ felt okay at the end but falls far short of the bold promise the title implied.

The Palpatine Saga

Since Rey is Palpatine’s granddaughter, then the final showdown of the Star Wars saga is actually between two Palpatines. Now we know that Vader never killed the emperor. So….the Chosen One, Anakin Skywalker, turning back to the good side doesn’t mean as much since the triumph of Return of the Jedi has no lasting impact. There never really was a return of the Jedi in this saga but instead the opposite, a return of the sith.

The Last Jedi

The Rise of Skywalker wastes far too much time fixing the very real errors left behind in The Last Jedi. J.J. Abrams addressed nearly every plot error to save the franchise, but he sacrificed a lot of the movie to achieve the feat. A lack of planning by LucasFilm put two directors with incompatible visions on a collision course for this trilogy, and we all paid the price.

Meh Space Battle

The final battle was much weaker in The Rise of Skywalker than in previous films. The space battle was mostly skipped in favor of Rey’s showdown with Palpatine. I also thought that Rey defeated the emperor a little too easily. While watching the movie trailer for The Rise of Skywalker, I cringed when I saw a bizarre cavalry charge along the hull of a star destroyer. And yikes. Seeing that charge in the film did nothing to justify such a ridiculous action sequence.

Missed Opportunities

Lastly, and you may not know this, but The Rise of Skywalker was supposed to feature the Force ghosts of Anakin Skywalker, Obi-Wan Kenobi, Qui-Gon Jinn, Yoda, Ahsoka Tano, Luminara Unduli, and Mace Windu during the climax. They shot the footage but it was all cut out of the film at the last second. Focusing solely on Rey at the expense of all the other characters seems like a mistake to me. The Rise of Skywalker isn’t just closing out one trilogy, but three.

Top 5 Things I Liked

Luke Skywalker

Luke Skywalker’s portrayal in The Last Jedi was a total mischaracterization. Actor Mark Hamill was very vocal in expressing his protest of Luke’s role in the new trilogy and we should deem the actor as a credible opinion of Luke’s character. The Rise of Skywalker restored Luke, even if they only gave him minimal screen time. I enjoyed a brief passing of true Jedi knowledge onto Rey. Luke sounded more like a Jedi Master and provided a more meaningful presence in the movie.

Likable Characters

Episode 9 puts camaraderie and friendship front and center and it pays dividends Finn, Poe, Rey, Kylo, Lando, C-3PO, and Luke are infinitely more likable in The Rise of Skywalker. When audiences care about the characters, stories live on. Finn, who had been reduced to a sidekick of Rose Tico in The Last Jedi, had a much better role. Poe also provided some light-hearted humor that The Rise of Skywalker needed. All the characters received a significant upgrade here.

Last Dance with Mary Sue

I’m a student of great heroines in fiction and film. I’ve been critical of Rey because she seems to win battles without any practice. In fact, Google Trends shows a massive spike in the use of the term “Mary Sue” with the release dates of Star Wars films and trailers. Rey has become synonymous with the term. However, The Rise of Skywalker is Rey’s best film, in my opinion. She finally loses to Kylo Ren in a lightsaber battle and overcomes a powerful system of deception aimed at hiding her identity. I dare say that I felt for Rey in The Rise of Skywalker. While I have criticism for Rey’s overall arc in this trilogy, in the end, I think she takes a rightful place in the Pantheon of heroines.

Reylo

I haven’t been a fan of the whole “Reylo” thing. However, I unexpectedly found myself enjoying the strange conflict between Rey and Kylo in this film. The writers had a better understanding of the relationship between Rey and Kylo and so, the scenes felt more genuine, more purposeful, and as a result, the film delivers more of an impact. We learn the source of Reylo as a true “dyad” of the Force. So, when Rey and Kylo finally join forces at the end, I enjoyed it. I liked seeing Kylo fight his way to Rey’s side. While flawed and confusing in previous films, Reylo mostly worked in the final installment.

The Soundtrack

John Williams comes through again with a sweeping score for Star Wars, and this time we know it’s his last. I’ve already bought the soundtrack and can’t wait to get to know the tracks by heart. I want to say “thank you” to John Williams, who in my opinion, is the true Chosen One of the Star Wars franchise, composing incredible and iconic music from 1977 to 2019.

Conclusion

While The Rise of Skywalker repairs the damage, the future may still not be bright for Star Wars. The media and corporate elites blamed and attacked Star Wars fans after The Last Jedi. The fans felt betrayed. It’s like catching your partner cheating on you (The Last Jedi) but who later apologizes (The Rise of Skywalker). The relationship still takes a serious hit. LucasFilm broke the trust of loyal fans around the world who made Star Wars one of the most profitable franchises in world history. That special bond may never be the same again.

Nov 21, 2019

Heroine-Centric Themes: Part 2

In a blog last month, I outlined the core concepts for a narrative monomyth I call the heroine’s labyrinth. This monomyth is a theoretical study into heroine-centric storytelling, in which I explore pervasive themes that recur in the plots, character development, and story structure. I believe the heroine’s labyrinth is a serious alternative to the long-standing hero’s journey and more. I further believe that our heroines are modeling alternative paths to heroic human action. Both models are completely valid and both models are inclusive to both genders.

But let’s take a closer look at heroines, shall we?

One major distinction between the heroine’s labyrinth and the hero’s journey is the nature of the villain. In the hero’s journey model, the villain tends to be an oppressive being from outside the hero’s native culture. This villain threatens to oppress or destroy the native culture, usually by force. I call this villain type the “distant dragon,” and the hero must depart from his native culture to slay this powerful villain.

In the heroine’s labyrinth, however, the villain is often a member of native culture, half benevolent, half oppressive. This villain already oppresses the native culture and as such, wears two faces. One face must be socially acceptable or even openly benevolent. The other face, though, is that of the tyrant and oppressor. I call this villain type the “masked minotaur.” While the masked minotaur tends to be a male figure, I will share some excellent examples of female minotaurs as well.

Once again, our heroines have a double purpose to their heroic actions. They do not merely fight the minotaur in single combat. No. Because the masked minotaur is a duplicitous villain, the heroine must first unmask the minotaur, no small feat by the way, and then they must defeat the minotaur. (Aside: heroines tend to pursue parallel or double goals all the time.)

A physical manifestation of the duplicitous villain is the double nature of the minotaur, itself. With the body of a human but the head and legs of a bull, the fusion evokes both the human and animal aspects of nature. Since the head is an animal but the body, human, we see that the minotaur ultimately thinks with the emotions of power, urge and ego, but will also exhibit positive human qualities through his human half—protection, stability, and the willingness to assume vital cultural responsibilities. The dual nature of the minotaur is thus a benevolent visible being, whom the native culture will protect, and also a hidden tyrannical being who oppresses, enslaves, and/or destroys. In some cases, the minotaur’s mask is merely a socially acceptable disguise designed to pass unnoticed within the native culture.

Either way, many heroines must solve the problem of the dual-natured villain. Unmasking the minotaur may lead to a real or perceived loss of the minotaur’s benevolent boon to the native culture.

On the last blog, many readers wanted examples of the core concepts behind the heroine’s labyrinth. Let’s take a look at some of the powerful masked minotaurs our heroines unmask in some of our favorite stories. I found overwhelming examples of heroines who unmask and then defeat a hidden minotaur within their naïve culture…here they are:

In the film Wonder Woman, Diana is out to destroy the spirit of war in all mankind, embodied in Ares, the God of War. When she defeats the obvious candidate, a World War 1 German general, she discovers the deception. The masked minotaur, Ares, is hidden among the Allies, the native culture on whose side she fights. An incredible deception, Ares is disguised as an armistice-seeking bureaucrat, wearing a benevolent outward face. Once Wonder Woman unmasks Ares, she then defeats him.

In Captain Marvel, Carol Danvers begins as a member and of the Kree civilization. In story terms, the Kree represents her native culture because her mentor, her friends, her role as a citizen, and her relationship to the supreme intelligence are all as a member of that culture. Yon-Rogg, played by Jude Law, is her charming mentor and combat instructor. He has her personal growth in mind when he trains her to use and control her powers. But, she eventually discovers the deception, unmasks Yon-Rogg as a villain holding her (and the galaxy) captive. Finally, she defeats him in combat once he’s unmasked.

In the film, Ex Machina, Eva is an advanced robot, designed to be the most human-like A.I. ever built. Nathan designed her, built her, and is the benevolent genius of a worldwide A.I. tech company. The outer face of Nathan is that of a paternal creator and eccentric savant, who simply wants Eva to be a conscious living being. But, as Eva learns, Nathan is also a brutal oppressor, who designs female robots for his own possession. She unmasks Nathan by guiding Caleb and once done, she defeats Nathan in combat.

In the brilliant novel Jane Eyre, the masked minotaur is actually a woman. Hidden in the vast estate of Mr. Rochester, Jane discovers a minotaur in the form of a half-mad, violent wife. The socially acceptable and legally-binding title of “wife” serves to oppress the heroine as well as many other characters. Although Jane doesn’t physically defeat the minotaur, she does overcome the mad wife by the novel’s end. The minotaur is not only within the native culture but inside the home.

In both Alien and Aliens, Ellen Ripley pulls double duty. Not only does she defeat a distant dragon (the alien and queen alien)—in both films, she must also unmask a hidden minotaur from her native culture. In Alien, Ripley unmasks the invaluable science officer, Ash, as a murderous android. And in Aliens, she famously unmasks Carter Berk, who had been helping and sticking up for Ripley at every turn, only to reveal a sinister willingness to betray everyone for personal gain.

In Coraline, the masked minotaur is also a woman and also inside the home. The seemingly benevolent, gift-giving, feast-cooking “Other Mother” is actually a tyrannical spider queen who seeks to possess the heroine.

In Tangled, the minotaur is Mother Gothel, who outlines her benevolent outer self in the hysterical song ‘Mother Knows Best.’ But, once unmasked by Rapunzel, we see that the minotaur is a vain creature who seeks to possess the heroine for all time to stay young. Mother Gothel is defeated once again, inside Rapunzel’s very home.

In Mad Max: Fury Road, the tough-as-nails Furiosa unmasks the head of her native culture Immortan Joe. He shows benevolence in his gushing gift of life-supporting water to the people. But in reality, he simply holds certain women in a captive maternal state while he enslaves his the native culture. Furiosa must unmask him and then defeat him.

In Hunger Games, Katniss Everdeen, too, must unmask the president of her native culture, President Snow. The unmasking of the minotaur is what leads toward revolution by the native culture.

In Coco, which follows the heroine’s labyrinth model, Miguel must unmask his own idol, Ernesto de la Cruz, as an oppressive minotaur who unfairly rules the underworld and destroyed his family.

In Aladdin, Jasmine must unmask Jafar.

In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy Gale famously unmasks the great and terrifying Wizard of Oz (with a little help from Toto).

In Silence of the Lambs, Clarice Starling must first unmask and then defeat the notorious serial killer, Buffalo Bill.

In Titanic, Rose must unmask and escape the seemingly benevolent, diamond-gifting Cal Hockley.

In Beauty and the Beast, the minotaur turns out to be hometown hunk, Gatson, whom Belle must unmask and defeat.

In Pan’s Labyrinth, the young Ophelia discovers the minotaur in her home environment as well. The minotaur is her own fascist stepfather, who cares only for having a son and nothing for his wife and stepdaughter.

Finally, in Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon, one of my all-time favorite heroine, Shu Lien unmasks the painted aristocrat’s daughter, Jen Yu, as the namesake, “hidden dragon.”

In all these cases and so many more, heroines are unmasking members of their native culture who hide in plain sight. I think this is a unique recurrent theme in the heroine’s labyrinth, in which the heroine models heroic behavior outside the traditional hero’s journey.

A great example of both storytelling models exactly side by side is Wreck-It Ralph. Ralph must leave his native culture to fight distant dragons and become worthy of a medal. Vanellope, though, must unmask King Candy as the sociopathic Turbo, who is the oppressive hidden minotaur within her native culture (or video game).

Most of these examples are in film because films are visual and immediately resonating. What do you think? If you have other examples of heroines unmasking hidden minotaurs, feel free to mention them below. More blogs about heroines will follow.

To learn more about the core concepts of the heroine’s labyrinth, click here