Aug 8, 2024

True hero’s journeys may be rarer than we previously thought. A journey that features a “departure” into exotic hinterlands is undoubtedly the stuff of cultural mythology. And yet, there are so many stories that don’t fit this mold. How else can we truly understand the story structure and character arc of Elisabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice? Or Janie Crawford in Their Eyes Were Watching God? Or Evelyn Wang in Everything Everywhere All at Once?

So, what makes the heroine-centric journey distinctive?

These heroines, just like Little Red Riding Hood and the Egyptian goddess, Isis, all faced conflicts within their native culture. From a pure storytelling standpoint, the heroine’s journey represents a fundamentally and existentially distinctive narrative model. So, let’s take a fresh look at heroine-centric stories. In order to fully appreciate the inward journey, we must first decouple it from the well-established hero’s journey.

The Hero’s Journey: Quick Overview

Joseph Campbell based his hero’s journey mainly on male protagonists in multicultural mythology and literature. He refers to this cultural hunter-warrior as the “hero” of the story. The hero’s story manifests into a hero’s journey. Campbell demonstrated that the hero’s journey was archetypally primal, culturally transcendent, and surprisingly timeless. The hunter-warrior departs the native culture and encounters exotic dangers far from the daily rhythms of life at home. Therefore, we must recognize that the hero’s journey, as originally conceived, defines an outward journey away from the native culture. This “outwardness” is essential to Campbell’s model and may even be foundational to the premise.

In The Hero with A Thousand Faces, Campbell identifies the first stage of the story as the “Departure” and the final stage as the “Return.” He states that the hero transfers “his spiritual center of gravity from within the pale of society to a zone unknown.” A guarded threshold often exists between the familiar native culture and the unknown outer regions. Campbell describes the unknown as “a distant land, a forest, a kingdom underground, beneath the waves, or above the sky, a secret island, lofty mountaintops,” and later, as “desert, jungle, deep sea, alien land.” These are descriptions of wilderness terrain or foreign environments. The cultural hunter-warrior departs the familiar and protective native culture, encounters hostile dangers, delivers a decisive victory, experiences personal growth, and then returns home with a boon.

Challenging Campbell

Maureen Murdock, however, recognized that the journey of the cultural hunter-warrior placed women in a secondary and reductive role. In her book The Heroine’s Journey: A Woman’s Quest for Wholeness, Murdock laid out numerous stages in a woman’s life. Examples include the “Separation from the Mother” and the “Body/Spirit Split.” She offered alternative archetypal and psychological stages that didn’t appear in Campbell’s model. Murdock leaned heavily on the experiences and testimonies of her female contemporaries. The focus was less on storytelling and more on archetypal womanhood. Although Murdock didn’t design her book for writing craft, she proved that Campbell didn’t address numerous feminine themes and realities.

The Universal Hero’s Journey

Christopher Vogler also addressed the limitations of Campbell’s hero’s journey. For example, he helped make the monomyth more accessible by universalizing the hero’s journey. Instead of a direct departure and return, Vogler offers a transition from the “Ordinary World” into the “Special World.” The structural and conceptual adjustment replaces the essential outward journey with a more universal change in overall story settings or conditions. Instead of a cultural hunter-warrior, we get a universal and gender-neutral hero who begins the story in the Ordinary World and moves into an extraordinary Special World.

Moreover, Vogler removed the more male-oriented story stages, such as “The Meeting with the Goddess” and “Woman as Temptress.” Finally, he condensed Campbell’s stages, simplifying the basic structure, making it more inclusive and writer-friendly while preserving the core concepts. Most writers today actually rely on Vogler’s “universal hero’s journey” more so than Campbell’s “cultural hunter-warrior’s journey.”

The Campbell and Vogler models persist in modern storytelling, but Murdock’s assertion that numerous feminine archetypes are missing continues to ring true. We’ve settled for a compromise. Vogler’s universalization process built greater space for female protagonists, intermeshing their journeys into the overarching framework and addressing other nuances that transcended the original hunter-warrior premise. His efforts resulted in a structural model that applied to most journeys in general.

Separating the Inward Journey

The time has come to separate the inward journey from the outward journey. Establishing the inward journey leaves Joseph Campbell’s cultural hunter-warrior and Vogler’s universal hero intact. However, we now have a clear third option that comes into focus—the heroine’s inward journey as a stand-alone, cross-cultural, and mythical experience. In keeping with the powerful resonance of the first two models, the heroine’s labyrinth exhibits feminine dynamism while also transcending gender altogether.

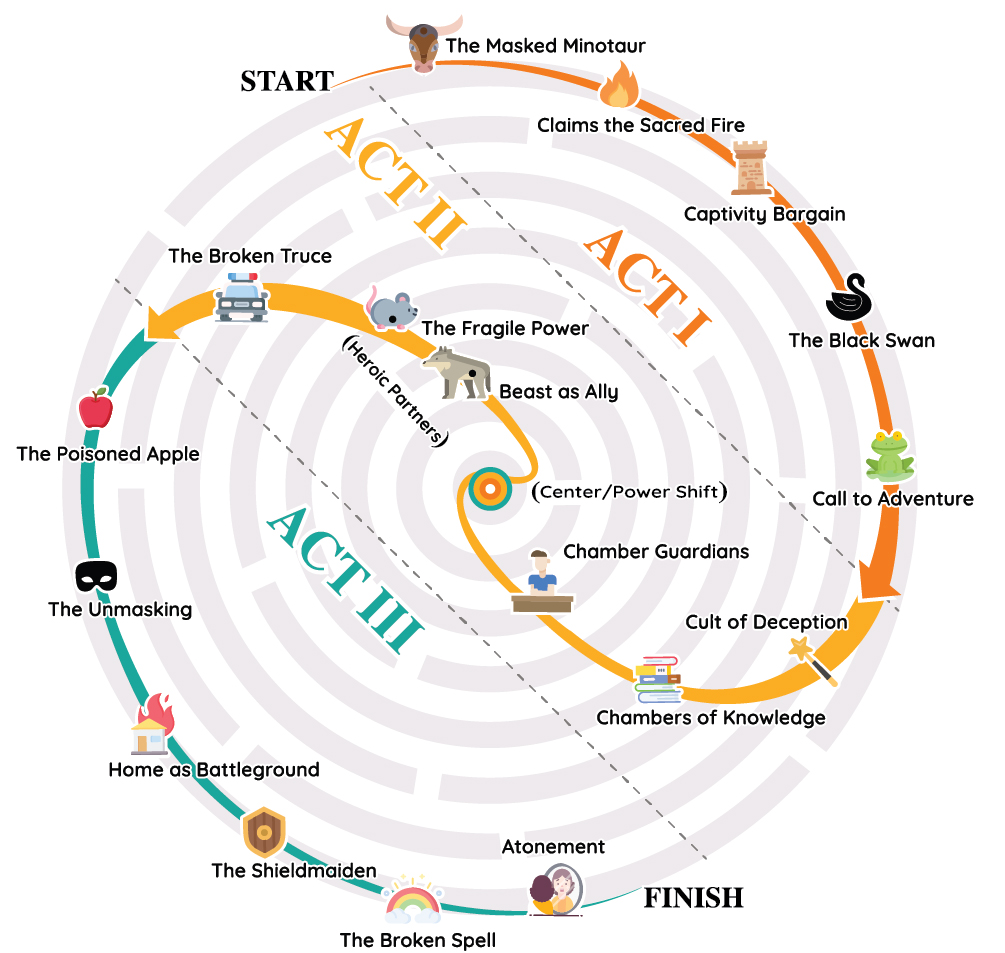

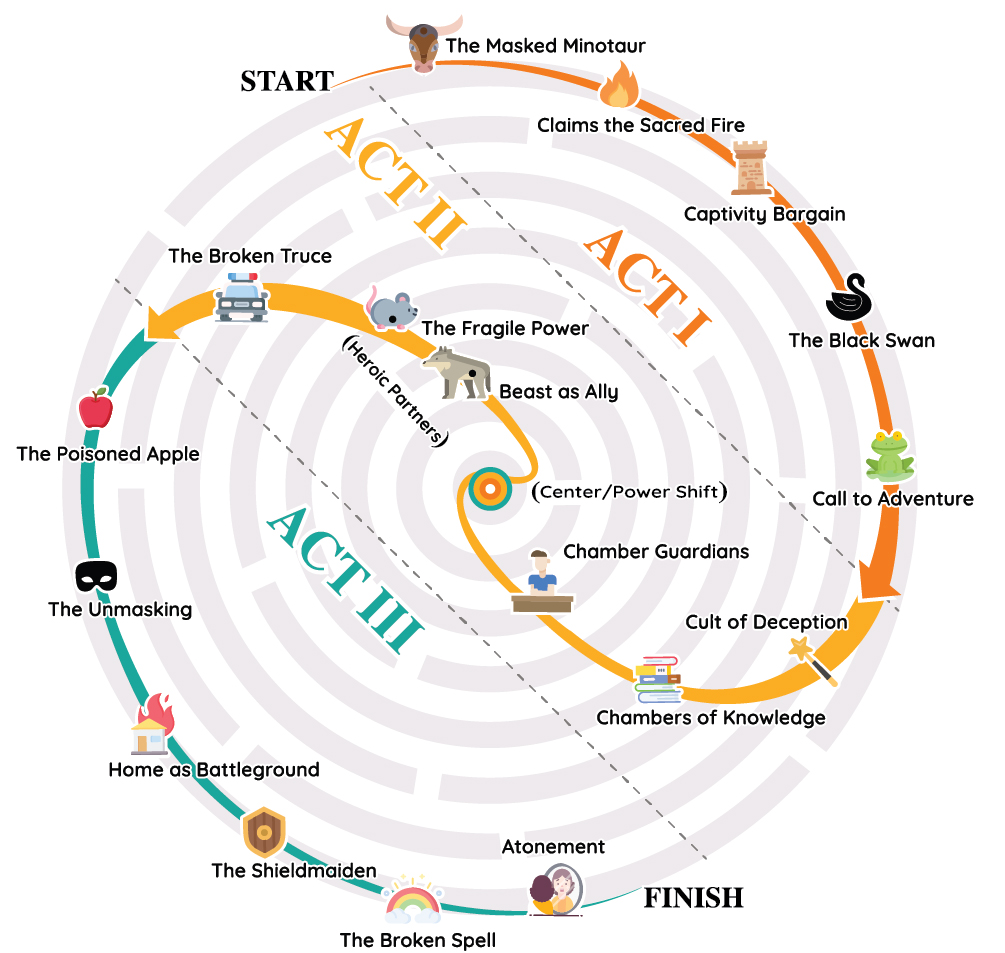

Below is the spiral design of the inward journey. The heroine travels deeper into the native culture before emerging out again. The growth arc features numerous distinctions.

Socio-Cultural Conflicts

The heroine’s labyrinth narrative model liberates itself entirely from the origins of a hunter-warrior story as modeled by mostly male protagonists. Secondly, the labyrinth separates itself even from the universalized hero’s journey, a variation rooted in Campbell’s departure and return. The heroine’s patterns and recurrent archetypes emerge authentically from stories with female protagonists once we affirm the structural uniqueness of the inward journey.

Instead of a departure from the native culture, we see countless heroines oriented to their societies, from which new but familiar conflicts take shape. Many heroine-centric stories also begin in the Ordinary World, as defined by Vogler, but develop a heightened focus on the social enculturation of the female protagonist. Heroines are often introduced to certain rules, gender roles, fixed traditions, superstitions, institutional methodology, social strategies, inherited customs, moral codes, community factions, family expectations, and cultural values. The confinement of the Ordinary World takes on greater significance because heroines didn’t always experience a total “departure” from society. The pressures of conformity within a social sphere did not establish “home” as a comforting place of safe returns. Instead, they lay the groundwork for a sustained conflict between culture and heroine throughout the story.

Hidden Mazes at Home

Culture itself becomes labyrinth-like for many heroines in fiction. Under wide-ranging cultural conditions, heroine-centric stories rarely feature a “threshold” beyond the native culture. Inside a labyrinth, a journey of many miles never strays far from the center, so a symbiotic relationship develops between the Ordinary and Special World for the heroine.

Why?

Because the Special World usually surrounds the heroine already. She sees and desires an unfiltered, unrestricted, and unprotected experience of her native culture. The heroine’s identity in the Ordinary World often prevents her from participating in the Special World. The two worlds are closer together in the heroine’s labyrinth–parallel–with the Special World hidden or forbidden. Even stories that appear to be an outward hero’s journeys require a second look. Heroine-centric stories such as Pan’s Labyrinth, Encanto, Alice in Wonderland, Labyrinth, Amélie, and Outlander all represent escapist journeys inside or near the heroine’s home. The events between the Ordinary and Special World are interrelated, and the decisions and consequences in one world affect the other.

In The Wizard of Oz, Coraline, Everything Everywhere All at Once, and Barbie have similar Special Worlds. Each “distant land” is actually a reimagining of the heroine’s home life with exotic doppelgangers of well-known friends, family members, or even themselves. Feelings of yearning, aspiration, and hope sit alongside feelings of frustration, repressed desire, and rebellion. We see the same socio-cultural conflicts in historical stories such as Memoirs of a Geisha, Jane Eyre, or I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. The journey is intimate and inward, familiar but different, yet strangely close to home. For the heroine, the unique relationship between the Ordinary and Special World replaces a linear outward threshold. The narrative experience is often both personal and deeply psychological. Therefore, the labyrinth perfectly symbolizing a full range of multilinear inward journeys–whether fantastical, realistic, or psychological.

Click here to see a six-minute video on the Labyrinth Archetype

Even in well-known short stories such as The Lottery by Shirley Jackson and The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, we see heroines at odds with their native culture. Their dangers are not far off, but nearby or inside the home. A cultural hunter-warrior or universal hero’s journey interpretation doesn’t adequately address the conflicts in heroine-centric stories. Campbell’s hero’s journey sidesteps most socio-cultural conflicts once the hero departs the home sphere. Vogler’s hero’s journey simplifies the Special World as a general shift in conditions. However, the heroine’s labyrinth elevates socio-cultural conflicts as a primary struggle. And so, we behold an alternative cultural figurehead in the heroine, whose growth doesn’t require a departure and return.

Different Journey, Different Villains

Villains, too, are affected by the structural reality of the inward journey. An overwhelming number of heroine-centric stories feature a duplicitous insider from within the native culture. Gone were the monstrous, out-in-the-open militant outsiders like Darth Vader, Thanos, the Kraken, Sauron, and Grendel. Instead of a “Distant Dragon,” heroines often face a dangerous “Masked Minotaur” from within their own native culture.

Heroines often encounter villains who are usually social apex characters. These villains appear pleasing or benevolent but hide a tyrannical side. The disguised or hidden villain brings an entire host of profound archetypal distinctions. These villains can come up close to the heroine, wield social power, and compromise the inner sanctums of society, if not the heroine’s home itself. A Masked Minotaur can also marshal social forces against the heroine. A desire to monopolize or possess the heroine often results in isolation or stigma. A villain disguised in the native culture is distinctive and archetypally profound. And like biblical Esther, the task of unmasking a socially esteemed villain often falls to the heroine.

See below for the heroine’s classic conflict triangle:

Inward Bound

The inward journey is timeless cross-cultural reality with deep archetypal truisms. The presence of distinctive archetypes along an inward journey does not invalidate the outward journey. The hero’s journey will likely remain the standard for an outward journey. However, the heroine’s labyrinth offers a new lens through which to examine and understand our stories.

In psychological, spiritual, and intellectual terms, the inward journey is nothing like the outward journey. Social anxiety, matters of personal identity, one’s role in society, pressure from trusted individuals, the social consequences of various relationships, disguised evils, professional endeavors, and navigating both public and private spheres all generate unique dangers, conflicts, and solutions. As such, the inward journey stands apart. The more we recognize the inward journey as a distinctive arc, the more we appreciate the labyrinth model. The heroine has much to teach us. The heroine’s story is our story; her struggles are our struggles, and her solutions provide a model of growth for all of us.

‘The Heroine’s Labyrinth: Archetypal Designs in Heroine-Led Fiction’ is a new approach to storytelling by author Douglas A. Burton. The writing craft book covers 18 unique archetypal patterns found in heroine-centric stories. Screenwriters, novelists, memoirists, and RPG gamers will all benefit from Burton’ fresh approach to storytelling.

Apr 13, 2021

For decades, Joseph Campell’s hero’s journey has been the primary model for narrative structure for writers around the world. This article is part of a series of articles that explores the “heroine’s labyrinth” as an alternative to the hero’s journey and focuses on the symbolism and archetypes of heroine-led fiction. Prior articles discussed the labyrinth versus the journey and examined the recurring villain archetype of the masked minotaur. This article goes right to the source of the heroine’s symbolic potential, her drive for individuation, and the competing forces that she must overcome. The sacred fire theme helps us understand the dynamism of conflict in heroine-led fiction.

Fire worship and sacred fires are intricately linked to mythology, folklore, and religion. In the novel, The Quest for Fire, prehistoric human tribes compete against each other to control fire, sometimes stealing away a burning log during a battle in hopes of keeping the fire ever-burning. Whoever has the fire, survives.

Fire usually represents a powerful, creative energy that can sustain life through heat, or bring light into darkness or craft materials to build tools or structures. But fire can just as easily represent a destructive force that can raze villages to ash, burn human beings, or spread violently out of control if mishandled. Therefore, fire is dual-natured in its potential for creation or destruction.

On the individual level, the sacred fire represents each person’s potential to be either an agent of creation or destruction. Such a powerful range of possibilities creates an ethical orientation for the heroine. Her choices matter. At the beginning of the story, the heroine is often depicted in an immature or inexperienced state. She’s becoming more aware of her agency, free will, or competency, which is to say, she’s becoming aware of her sacred fire. The heroine must claim her sacred fire by expressing some move toward greater freedom and expressing interest in the outside world.

There is a catch though.

The heroine’s claim upon her sacred fire introduces two other claimants—the native culture and the masked minotaur. Let’s take a closer look at the meaning behind all three claims to the sacred fire.

The Heroine’s Claim

The heroine’s sacred fire symbolizes her vast untapped, untested, and unrealized human potential. She has aspirations that exceed her current reality. The colorful and exotic native culture is just outside her window and the heroine intends to merge with that world. She’s aware of her potential and relies upon her imagination to compensate for her lack of experience. This vital pulse of the human spirit is relatable to all of us. We are stirred to the core when the heroine claims her sacred fire in fiction.

Musicals provide excellent examples of sacred fire moments because they are so brazen and memorable. Whatever forces have kept the heroine in her immature state, she’s ready to take a chance on herself and face the world. Elsa vows boldly to let it go. Moana declares her intent to see how far she’ll go. And poor Rapunzel wants to know just when will her life begin. And that’s just Disney. Sacred fire songs are common in many musicals, such as Dorothy Gale’s desire to go somewhere over the rainbow in The Wizard of Oz, or Roxy Hart’s dream to be the name on everybody’s lips in Chicago. These opening numbers are great examples of a heroine’s inner desire for self-actualization outside the labyrinth.

The “sacred fire” moment in the story, whether it’s a specific scene or a musical number, shows the audience or reader that the heroine has her own desires, her own vision, and her own unique outlook on the world. She’s ready. If done correctly, the heroine’s sacred fire moment can be incredibly powerful.

As readers or viewers, whenever the heroine claims her sacred fire, we feel the heroine’s first attempt at empowerment. All that unrealized potential is bubbling up and meeting us at a conscious and subconscious level. The heroine is building her will to act on her aspirations because she has found the words or actions to give force to the feeling. But while the heroine’s sacred fire moment throws a gauntlet at the world, trust me—the world responds to the challenge.

The Native Culture’s Claim

The heroine soon realizes that her native culture’s claim has been staked out long in advance. Whereas the symbolic power for the heroine is individual potential, the symbolic power of the native culture is communal continuity.

A continuous fire that burns through the passage of time links the present moment to the distant past when the flame had been first lit. If the flame goes out, then the continuity breaks—and whatever the flame represented is diminished in the world. All too often in heroine-centric stories, the native culture interprets continuity very narrowly as marriage and children. That’s why so many stories feature a socio-cultural labyrinth designed to steer the heroine toward the archetypes of the innocent virgin, the fertile bride, and the chaste mother—the three archetypes so prized by cultures worldwide.

Therefore, the labyrinth in a feminine monomyth symbolizes the long-standing and highly developed claim that society places upon the heroine.

Each one of us, men and women alike, stands atop trillions of decisions made by thousands of generations of human beings who solved the problems of survival and answered the questions of what it means to be human. They made decisions while facing annihilation by nature, subjugation from rival tribes or civilizations, and warding off collapse from within. Somehow, they made it and we exist today because our ancestors got something right. All fictional characters come from someplace geographically and speak a specific language. This inescapable anchor of human reality means that much of our personal identity comes down to us from something human that came before—our native culture. The phrase “passing the torch” is quite literally the passing of human knowledge, experience, ethics, skills, history, and survival strategies from one generation to the next.

The tension between the competing claims will immediately generate conflict. The sacred fire has been passed to the heroine, now she must pass the flame on to a new generation. But rearing children, while vital to survival, isn’t the only way a sacred fire can transfer from one generation to the next. Stories usually explore all the ways a heroine may contribute and in many cases, the heroine must overcome social expectations and pressures to pass on her sacred fire.

The transmission of specific ideas beyond animal instinct is a uniquely human aspect. Whether we’re talking about music, medicine, or good stories, ideas can also pass through time just as well as our genes. The heroine’s understanding of the world is still within the context of her culture—and so we must understand that the sacred fire that the heroine claims, did come down through the generations through the native culture. This makes the native culture’s claim to the sacred fire a powerful one.

Daenerys Targaryen in Game of Thrones provides an excellent example of the relationship between the heroine’s individuation and the influence of the native culture. First, she is a descendent of the Targaryen bloodline and so she inherits a title, a great house, a history, and the blood of the dragon, which means she cannot be burnt by fire. The three dragons are nearly perfect symbols of Daenerys’ growing potential for the creation of a better world or total destruction through conquest. Throughout the story, we see Daenerys struggle with moral decisions on a regular basis. She demonstrates an incredible individual will of her own and directs many events in the story on her rise to power. She’s as sovereign as they come. But we must not forget that her mission, her vision, and much of her orientation toward the world still stems from the sacred fire passed on to her from her native culture. She never forgets the Targaryen outlook on the world.

In the end, Daenerys oddly attempts to destroy forever the link between her powerful agency and the native culture from which she comes. And she fails.

In many stories, purging either one of the dual natures often leads the heroine to destroy either herself or the native culture, and both are tragic ends. If the heroine subordinates herself entirely to the native culture, she risks destruction at the total loss of self. Like a cult member, the heroine surrenders all individual agency for the demands of the group. Her world shrinks and the trapped heroine loses her human vitality and creative force.

But if the heroine rejects entirely the native culture from where her sacred fire originated, then she risks becoming lost in self-serving quests. She may even come to covet the sacred fire of others or seek out a substitute culture to compensate for the loss. These heroines may even become villains, such as Ursula from The Little Mermaid who gathers souls, or Agatha Harkness in WandaVision, who tries to physically steal Wanda’s sacred fire.

Bear in mind, the feminine monomyth isn’t confined to reinforce the claim of the native culture, but often the opposite. The heroine’s labyrinth is a natural storytelling model that shows us how to break gender norms, push back on social expectations, or challenge outdated traditions rather than blindly follow them. The general goal becomes the self-realization of the heroine’s individuation while also adding value to the continuity of the native culture.

Therefore, the heroine must achieve the proper balance between personal sovereignty and some form of continuity with the valuable human knowledge and experience that came before her.

And to add to this ancient conflict, there is yet a third claimant.

The Minotaur’s Claim

We already discussed the general attributes of the masked minotaur, namely, that they are almost always members of the native culture, they wear a socially acceptable mask while also hiding an oppressive side, and they exhibit a form of possessive love. But the symbolism of the sacred fire provides another layer of understanding about the masked minotaur.

In so many heroine-centric stories, the masked minotaur claims the heroine’s sacred fire for his or her own purposes. And where the native culture’s claim is socially pervasive, the minotaur’s claim is more individualized and self-serving. This selfish aspect introduces a dark and destructive force that threatens to monopolize the creative powers of the heroine. Therefore, the heroine must also overcome the minotaur’s pure and tyrannical claim to her sacred fire. In so many stories, the minotaur often covets the heroine’s feminine essence, her creative powers and energy, and yes, her beauty and eros. The minotaur is usually unable to see past these aspects of the heroine’s sacred fire.

In many heroine-centric stories, you’ll find common cause between the native culture and the masked minotaur. Whenever the minotaur appears as a potential suitor for the heroine, the possessive love of the minotaur aligns with the desire for continuity of the native culture through marriage (and children). Therefore, the native culture and the masked minotaur form a persistent alliance in heroine-centric stories.

In Titanic, the masked minotaur is Cal Hockley, who seeks to possess Rose Dewitt Bukater as his wife. Rose’s mother represents the interests of the native culture and implores Rose that the sacred fire might be extinguished if she doesn’t marry. Rose intuitively understands that accepting Cal’s offer of marriage will destroy her true inner self.

In Tangled, the sacred fire of the heroine is beautifully exemplified by the magic of Rapunzel’s hair. Her long hair is symbolic of her creative power because it restores youth and extends life. Mother Gothel, who is the masked minotaur, hordes the sacred fire to satisfy the vanity of eternal beauty. Locking Rapunzel in a tower perfectly captures the self-serving mentality of the minotaur’s claim. The heroine’s free will is devalued and suppressed.

Beauty and the Beast provides a perfect example of all three claims to the sacred fire being made at the same time. In the opening number, Belle expresses her sacred fire moment by wanting so much more than her provincial life. The townsfolk, on the other hand, make a bevy of remarks aimed at Belle’s non-conformity to the values of the native culture. And finally, Gaston is the masked minotaur of the story, who arrogantly claims Belle as his future wife. Everyone, it seems, seeks the sacred fire of the heroine for a different reason.

Protecting the Sacred Fire

By understanding the archetypal significance of the sacred fire, we can better appreciate the conflict of our favorite heroines. The opening scene to Star Wars: A New Hope, for example, takes on a whole new meaning. The film opens not with Luke Skywalker, but with Princess Leia. She’s desperately attempting to flee with the stolen plans to the dreaded Death Star. But the masked minotaur, Darth Vader, is bearing down on her in a menacing fashion (the head of the star destroyer even looks like a minotaur’s head).

On the surface, Vader is after the Death Star plans. But in archetypal and symbolic terms, Vader is after the deeper symbol that Princess Leia carries with her. She holds a fragile sacred fire—the life force of the entire Rebellion. If she fails, then the life of the Rebel Alliance will be put out across the galaxy. Subconsciously, we recognize that the flame—the continuity of the rebellion—is in Princess Leia’s hands as she races from danger. And the imagery in the film strikes at the very heart of our human subconscious.

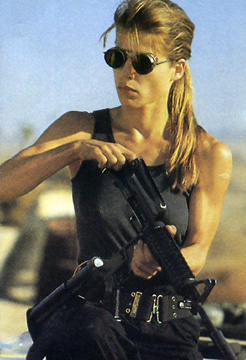

The same is true of Sarah Connor in the first two Terminator films. On the surface, Sarah is trying to survive because her unborn son, John Connor, is the future leader of the human resistance. So much criticism is directed at the idea that Sarah Connor plays second fiddle to John Connor, or that her value is confined to giving birth to a man who will save the world. But once again, we must look deeper into the symbolism. Sarah’s value extends far beyond motherhood. Think about it. Sarah would likely protect John’s life even if he was a tax accountant because most parents don’t need an excuse to protect children.

Screencap from Terminator 2: Judgment Day, TriStar Pictures 1991.

But Sarah isn’t just protecting one unborn child. She’s protecting three billion human lives from a future nuclear holocaust. Therefore, Sarah carries the eternal flame of all humanity. She carries humanity’s very right to exist. And our heroine is haunted by the sacred fire that she carries. When Sarah sleeps, her nightmares are not of John’s death, but of Judgement Day and the nuclear holocaust that obliterates billions of human beings. The story was never about John. It’s always been about Sarah and her desperate effort to protect the sacred fire from going out. That’s probably why subsequent films that centered on John Connor all failed, while Sarah Connor’s legacy has withstood the test of time.

Moana is just as much a story about Te Fiti as it is about Moana. Once again, like Princess Leia and Sarah Connor, Te Fiti carries the life force of the islands and sea. In the mythology of Moana, Te Fiti’s sacred fire is symbolized by the green Pulau stone. But the masked minotaur of the story, Maui, seeks to possess the goddess’ sacred fire and succeeds in stealing the Pulau stone. With her sacred fire stolen, Te Fiti becomes Te Ka, an angry goddess made of volcanic fire. She then becomes hostile and destroys life through the islands and sea. Only when Moana returns the sacred fire to Te Ka, does the goddess return to her original self. And life returns in spectacular fashion.

Sacred Fire in the Hero’s Journey

The sacred fire is not unique to heroine-centric stories. In fact, the basic concept is very much the same between both storytelling models. Like our heroines, our heroes also contend with the native culture for independence. The hero, too, can claim their sacred fire for creative or destructive purposes. However, the hero’s journey tends to emphasize the continuity of the native culture through the hero’s mastery of cultural skills and atonement with the father.

Probably one of the best examples of the sacred fire with a hero’s journey is the 1978 movie, Superman. The sacred fire is perfectly symbolized by the green crystal of Krypton. This glowing flame comes from the native culture and is passed to Clark. The crystal represents both the continuity of Krypton as well as Clark’s individual potential as Superman.

Summary

The sacred fire symbolizes the heroine’s vast human potential for creative good or destructive evil.

The heroine claims her sacred fire by expressing her personal desires, which then sets up the conflict between the heroine, the native culture, and the masked minotaur.

To the native culture, the sacred fire symbolizes the continuity of the tribe.

There remains a powerful bond between the heroine’s individual free will and her identity within the native culture.

The masked minotaur attempts to possess the sacred fire for selfish purposes

In the next article, we’ll explore the heroine’s first attempt to solve the three claims to her sacred fire–“the captivity bargain.”

Oct 9, 2020

Many adventure stories, such as ‘The Hobbit,’ use most of the pages moving through liminal space. The main character, Bilbo Baggins, is traveling through exotic settings, far beyond the comforts of home. Liminal space is the “space” between two destinations and as far as the main character is concerned, it is also the space between two different realities.

The most common usage of liminal space is when the heroic figure leaves the safety and protection of their home, and travels toward an unfamiliar and potentially dangerous destination. The heroic figure has left their home behind, and yet they are nowhere, in limbo somewhere. Not all stories are adventure stories, and so liminal space may be a usable theme for a single chapter or even a handful of paragraphs. However, understanding the deeper psychological power of a concept such as liminal space can help a writer spot opportunities to elevate their writing. As a storyteller, you must recognize the significance of liminal space and design a setting that connects to your readers on a primal level and add extra punch to your world and story.

Change begins in liminal space.

Psychologist Carl Jung states, “Individuation begins with a withdrawal from normal modes of socialization, epitomized by the breakdown of the persona.” He calls this withdrawal a “movement through liminal space and time, from disorientation to integration.”

Liminal space typically features four themes:

- Unconsciousness—either fainting, sleeping, or dreaming.

- Transitive setting— physically moving the character between destinations

- Security blanket—an object that symbolizes the familiarity of home.

- Harsh environment— either vast and empty or through a tunnel-like passageway

Most heroic figures, just like you and me, inwardly want to avoid danger. Therefore, our heroines and heroes often “faint” as a defense mechanism when it’s time to face the dangerous and uncertain world. The overtones of disorientation and unconsciousness appear often as our characters enter liminal space. They are infants about to be born. Recognize that. Know that we are looking at our innocent, untested heroic figure and pushing her or him out toward the hazardous world.

Whenever liminal space is portrayed as a vast and empty expanse, like a desert or ocean, it’s to underscore the uncertainty and smallness your heroic figure feels. Whenever liminal space is instead represented by a tunnel-like passageway, it’s to represent a birth canal, the movement away from the safety of the womb.

Liminal space also cues your readers that change has come…is happening now. The heroine or hero is disoriented. They faint or travel through a strange environment and cling to an object that reminds them of home.

Examples of liminal space:

In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy falls into a dream-like state during the tumult of nasty twister. The tornado (a tunnel) lifts her actual home into the sky and away from familiar Kansas. Out of her window, she sees familiar objects and people from Kansas whizzing about, but soon the window reveals the dangerous sight of the Wicked Witch, who tyrannizes the Otherworld ahead. Toto comes with Dorothy and stands in as a familiar reminder of the home she left behind. “Toto, I have a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.”

In Star Wars, Luke Skywalker leaves home for the last time, though he doesn’t know it, to search for the runaway Artoo Detoo. When he encounters the Sand People, Luke immediately faints, which cues viewers that Luke is about to move beyond his familiar world. He soon discovers the death of his uncle and aunt and enters the unpredictable Mos Eisley Spaceport, a place of transit. When he travels aboard the Millennium Falcon, he experiences hyperspace, which is a tunnel of light. “Traveling through hyperspace ain’t like dusting crop, boy!”

In the Matrix, the heroic figure of Neo is flushed through a tunnel and pulled into the “real world” by a giant claw. The imagery is unmistakably themed around the shock of being born. Morpheus soon shows Neo an empty white space called, the Construct, which he describes as “the place in between the neural-interactive simulation of the Matrix.” He even refers to the world as the “desert” of the real. After Morpheus shows Neo the Matrix, the hero falls to the floor and goes unconscious. “He’s gonna pop.”

In the movie Coraline, our young heroine must first fall to sleep and dream before she can cross into the Otherworld. Once asleep, Coraline opens a secret door and must crawl through a mysterious tunnel of cobwebs and dust. All the objects of her home surround her but offer the illusion of a better home. “You know you can stay here forever. There’s just one condition.”

In Wonder Woman, when Diana leaves her home behind, she boards a boat that must cross a vast and empty sea. She brings her gauntlets, shield, and sword with her. Once aboard, Diana lays down and sleeps. Her mother warns her: “You know that if you choose to leave, you may never return.”

Avatar features liminal space both in hypersleep en route to Pandora, which floats through the vastness of space. Jake Sully’s wheelchair, a symbol of his weaker, dependent earthly life comes with him to the distant planet. Jake must also “faint” each time he enters his Avatar body by sleeping in a link pod. Each time, his consciousness travels through a tunnel. “Everything is backwards now, like out there is the true world, and in here is the dream.”

In Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon, the mother of the aristocratic Jen Yu falls unconscious when the bandits attack. Jen then pursues a bandit to retrieve her ivory comb, which is the object that symbolizes her aristocratic home life. Rather quickly, Jen finds herself surrounded by a vast and empty desert. “All this trouble for a comb?”

In Fight Club, the narrator’s home life is cut off when his condo (home) is destroyed by an explosion. Like Coraline, he finds an “opposite” home when he wanders off to the empty “toxic waste part of town” to squat in an abandoned house. He keeps his briefcase, a stark reminder of the shallow corporate life he left behind. The narrator faints all the time due to narcolepsy. He even states, “If you wake up at a different time in a different place, could you wake up as a different person?”

Like any step in the heroic transfiguration, liminal space, too, can be expanded upon in amazing ways. The movie Gravity features a heroic figure who’s trapped in liminal space, haunted by ghosts of familiar astronauts and listening to folksy transmissions from the earth below. She’s even filmed floating in zero gravity in the fetal position at one point, an image that evokes feelings of infancy and smallness when faced with the dangerous world just beyond.

Liminal space is a powerful tool for writers. Take a look at your scenes and see if there’s an opportunity to expand an existing scene using the tools discussed above. Be creative. Design a liminal space that echoes your unique world and captures the primal imagery of human change. Our subconscious minds will recognize your handy work, even if our conscious minds do not.

Douglas A. Burton is an award-winning author who studies the phenomenon of heroic figures in fiction. His critically-acclaimed historical fiction novel, ‘Far Away Bird’ features the origin story of Byzantine Empress Theodora. The writing experience led Doug to outline and propose a narrative monomyth for female-oriented fiction that he calls the heroine’s labyrinth, an alternative to the hero’s journey. To see the stages of the heroine’s labyrinth, click here.

May 20, 2020

Welcome to the fourth installment in a series of articles that looks at the heroine archetype and the recurrent themes found within heroine-centric stories. This article expands on the heroine’s labyrinth for narrative story structure as an alternative to the hero’s journey. Here are the story elements of the heroine’s labyrinth that we’ve covered in previous articles:

- Heroines often struggle against the social rules of their native culture.

- Villains follow the “minotaur” archetype, who are usually members of the heroine’s native culture.

- The minotaur is “masked,” hidden, or disguised, appearing half-benevolent, half oppressive.

- Heroines must first unmask the minotaur before the final battle.

- The heroine’s final battle is not far off, but often inside the home (or on home turf).

- The heroine often provides a model for breaking with certain gender roles or social norms.

- Heroine-centric journeys tend to be circular and inward, rather than linear and outward.

This week, I want to discuss one of the most heroic aspects in all fiction, the Shield-Maiden Moment. Structurally, the shield-maiden moment occurs in the third act, right before the final confrontation with the villain. However, it can occur earlier as an emergence moment for the heroine as well. This is a moment where the heroine physically interposes herself in between the minotaur and a defenseless life, typically just a few feet away.

Symbolically, the heroine becomes a human shield against the forces of violence and destruction. She holds her ground and stands face-to-face against brute power as the ultimate and sometimes unexpected first responder. This is a special dynamic for combat in fiction because it carries a dual role. The heroine must not only defeat the fearsome minotaur, who is a serious physical threat, but she must also save another potential victim. The heroine is not acting in the manner of self-sacrifice, although it may appear that way—because her mission cannot allow her to fail. If she’s defeated, not only is she captured or destroyed, but the life she defends will also be captured or destroyed.

How does this contrast with the hero’s journey?

In the hero’s journey, the male-oriented hero typically confronts a menacing “dragon,” who typically comes from outside the native culture. The dragon is exotic, dangerous, and threatens the native culture with destruction or oppression. The hero eventually faces the dragon in single combat. The meaning of the combat is typically a test of worthiness for the hero, with the dark archetype of evil on one side and the light archetype of good on the other. It’s powerful imagery that recurs with serious regularity. Whether it’s Luke Skywalker facing Darth Vader on Bespin, Neo staring down Agent Smith inside the Matrix, or Captain America versus Red Skull in Nazi Germany, the basic design is the same. The hero has undergone their trials and must test their mettle against a villain who doesn’t lose. Like two rams about to rise and smash heads, this recurrent theme tells readers or viewers that we are in the final stages of a story and that the conflict will be resolved in this battle.

For the heroine’s labyrinth, facing a villain while also protecting life is an amazing contrast and perhaps, the most heroic moment in fiction. The Shield-Maiden moment happens whether the heroine has training or not, whether she is prepared or not. And quite often, the minotaur cheats to secure victory. All forms of power and deception are brought to bear upon the heroine, and yet she prevails. She accomplishes her dual mission—to defeat the minotaur in combat and to protect a living being in close proximity. Truly inspiring. Examples of the Shield-Maiden Moment are everywhere. Here are just a few:

In Aliens, Ripley famously marches up to battle the Queen alien in dramatic fashion. She’s facing a monster that has an overwhelming physical advantage. Her famous line, “Get away from her you bitch” almost perfectly captures the heroine’s stunning willingness to face insurmountable odds when her Shield Maiden Moment arrives.

In The Silence of the Lambs, heroine Clarice Starling confronts serial killer Buffalo Bill with defenseless Catherine Martin trapped in well right behind her.

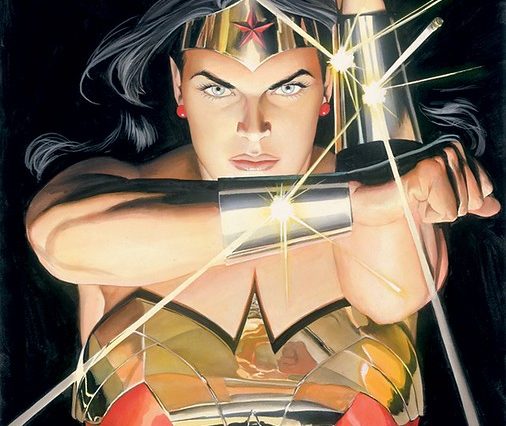

Perhaps one of the most striking examples of the Shield Maiden Moment is in Wonder Woman. Who can ever forget the images of Wonder Woman striding across No-Man’s Land, and then holding up an actual shield while enduring a storm of machine-gun fire, her legs buckling under the strain? She leads the way while the vulnerable Allied infantry mounts a charge across the deadly landscape. Even in the final battle, when Wonder Woman fights the God of War—she must enter battle with Steve Trevor, her love interest, sharing the battlefield with her.

In Moana, the heroic Maui is wounded and without his weapon in the final moments of the battle. He is seconds from destruction as Te Ka rears back for a fatal blow. But, in one of my favorite Shield-Maiden moments, Moana boldly reveals herself by holding up the heart stone to momentarily stop Te Ka. Moana not only makes a stand but goes on to walk bravely up to the villain and heal Te Ka’s heart. This restores the feminine spirit of the world, thus saving it.

In The Terminator, Sarah Connor, who is a server at a diner, fights and defeats an actual terminator while dragging and protecting a defenseless Kyle Reese. Then again, in Terminator 2, Sarah faces down a nearly invincible T-1000 with her son, a young John Connor, standing right behind her.

In Avengers: Infinity War, Scarlet Witch boldly stands against Thanos, summoning a shield of red magic as the overpowering villain closes in. Behind her, a weakened Vision lays on the ground, unable to defend himself.

Brienne of Tarth from Game of Thrones is the ultimate shield maiden. Nearly all her combat involves the valiant protection of life, from Caitlyn Stark to Jaime Lannister. Time and time again, Brienne steps in front of dangerous men as a bodyguard and prevails.

In Avatar, Neytiri takes down Colonel Quaritch in the final battle, while the small human form of Jake Sully, who is physically paralyzed and suffocating, lays in his avatar pod behind her.

In Tangled, Rapunzel duels against her false mother with Flynn Rider laying wounded on the ground at ger back. Again, the heroine’s battlefield is crowded with others.

In The Lord of the Rings, it is Aowyn who steps in front of the Witch-King when King Théoden falls in battle. When the Nazgul declares that “no man can kill me,” she famously responds, “I am no man.” She then destroys the Nazgul while sustaining terrible injuries.

In Kill Bill, Beatrix Kiddo enters combat against Bill while her daughter, whose existence was just revealed to her, stands in the room just a few feet away.

In The Fifth Element, Leloo, herself, is physically the ‘element’ that will shield the earth from a giant ball of black fire. And her powerful mantra is “protect life.” How fitting.

In Ex Machina, the android heroine, Eva, turns and faces Nathan, the minotaur in the center of the labyrinth. Behind her is another captive android woman. Once again, Eva, herself, becomes a physical shield as Nathan smashes Eva’s limbs. Nathan is defeated and Eva escapes the labyrinth.

When the hidden minotaur strikes in Jane Eyre, it is Jane who steps in and saves a defenseless Mr. Rochester during the blazing fire.

Even in The Force Awakens, Rey fights Kylo Ren with a wounded and defenseless Finn laying in the snow behind her.

The next time you’re in danger, hopefully, there’s a heroine nearby.

For a more in-depth look at all the steps in the heroine’s labyrinth, click here.

Douglas A. Burton’s award-winning debut novel, Far Away Bird, applied the heroine’s labyrinth story model to one of history’s most influential women, Empress Theodora. Far Away Bird is available in paperback on Amazon and audiobook on Audible.com.

Here are the prior articles:

Nov 21, 2019

Heroine-Centric Themes: Part 2

In a blog last month, I outlined the core concepts for a narrative monomyth I call the heroine’s labyrinth. This monomyth is a theoretical study into heroine-centric storytelling, in which I explore pervasive themes that recur in the plots, character development, and story structure. I believe the heroine’s labyrinth is a serious alternative to the long-standing hero’s journey and more. I further believe that our heroines are modeling alternative paths to heroic human action. Both models are completely valid and both models are inclusive to both genders.

But let’s take a closer look at heroines, shall we?

One major distinction between the heroine’s labyrinth and the hero’s journey is the nature of the villain. In the hero’s journey model, the villain tends to be an oppressive being from outside the hero’s native culture. This villain threatens to oppress or destroy the native culture, usually by force. I call this villain type the “distant dragon,” and the hero must depart from his native culture to slay this powerful villain.

In the heroine’s labyrinth, however, the villain is often a member of native culture, half benevolent, half oppressive. This villain already oppresses the native culture and as such, wears two faces. One face must be socially acceptable or even openly benevolent. The other face, though, is that of the tyrant and oppressor. I call this villain type the “masked minotaur.” While the masked minotaur tends to be a male figure, I will share some excellent examples of female minotaurs as well.

Once again, our heroines have a double purpose to their heroic actions. They do not merely fight the minotaur in single combat. No. Because the masked minotaur is a duplicitous villain, the heroine must first unmask the minotaur, no small feat by the way, and then they must defeat the minotaur. (Aside: heroines tend to pursue parallel or double goals all the time.)

A physical manifestation of the duplicitous villain is the double nature of the minotaur, itself. With the body of a human but the head and legs of a bull, the fusion evokes both the human and animal aspects of nature. Since the head is an animal but the body, human, we see that the minotaur ultimately thinks with the emotions of power, urge and ego, but will also exhibit positive human qualities through his human half—protection, stability, and the willingness to assume vital cultural responsibilities. The dual nature of the minotaur is thus a benevolent visible being, whom the native culture will protect, and also a hidden tyrannical being who oppresses, enslaves, and/or destroys. In some cases, the minotaur’s mask is merely a socially acceptable disguise designed to pass unnoticed within the native culture.

Either way, many heroines must solve the problem of the dual-natured villain. Unmasking the minotaur may lead to a real or perceived loss of the minotaur’s benevolent boon to the native culture.

On the last blog, many readers wanted examples of the core concepts behind the heroine’s labyrinth. Let’s take a look at some of the powerful masked minotaurs our heroines unmask in some of our favorite stories. I found overwhelming examples of heroines who unmask and then defeat a hidden minotaur within their naïve culture…here they are:

In the film Wonder Woman, Diana is out to destroy the spirit of war in all mankind, embodied in Ares, the God of War. When she defeats the obvious candidate, a World War 1 German general, she discovers the deception. The masked minotaur, Ares, is hidden among the Allies, the native culture on whose side she fights. An incredible deception, Ares is disguised as an armistice-seeking bureaucrat, wearing a benevolent outward face. Once Wonder Woman unmasks Ares, she then defeats him.

In Captain Marvel, Carol Danvers begins as a member and of the Kree civilization. In story terms, the Kree represents her native culture because her mentor, her friends, her role as a citizen, and her relationship to the supreme intelligence are all as a member of that culture. Yon-Rogg, played by Jude Law, is her charming mentor and combat instructor. He has her personal growth in mind when he trains her to use and control her powers. But, she eventually discovers the deception, unmasks Yon-Rogg as a villain holding her (and the galaxy) captive. Finally, she defeats him in combat once he’s unmasked.

In the film, Ex Machina, Eva is an advanced robot, designed to be the most human-like A.I. ever built. Nathan designed her, built her, and is the benevolent genius of a worldwide A.I. tech company. The outer face of Nathan is that of a paternal creator and eccentric savant, who simply wants Eva to be a conscious living being. But, as Eva learns, Nathan is also a brutal oppressor, who designs female robots for his own possession. She unmasks Nathan by guiding Caleb and once done, she defeats Nathan in combat.

In the brilliant novel Jane Eyre, the masked minotaur is actually a woman. Hidden in the vast estate of Mr. Rochester, Jane discovers a minotaur in the form of a half-mad, violent wife. The socially acceptable and legally-binding title of “wife” serves to oppress the heroine as well as many other characters. Although Jane doesn’t physically defeat the minotaur, she does overcome the mad wife by the novel’s end. The minotaur is not only within the native culture but inside the home.

In both Alien and Aliens, Ellen Ripley pulls double duty. Not only does she defeat a distant dragon (the alien and queen alien)—in both films, she must also unmask a hidden minotaur from her native culture. In Alien, Ripley unmasks the invaluable science officer, Ash, as a murderous android. And in Aliens, she famously unmasks Carter Berk, who had been helping and sticking up for Ripley at every turn, only to reveal a sinister willingness to betray everyone for personal gain.

In Coraline, the masked minotaur is also a woman and also inside the home. The seemingly benevolent, gift-giving, feast-cooking “Other Mother” is actually a tyrannical spider queen who seeks to possess the heroine.

In Tangled, the minotaur is Mother Gothel, who outlines her benevolent outer self in the hysterical song ‘Mother Knows Best.’ But, once unmasked by Rapunzel, we see that the minotaur is a vain creature who seeks to possess the heroine for all time to stay young. Mother Gothel is defeated once again, inside Rapunzel’s very home.

In Mad Max: Fury Road, the tough-as-nails Furiosa unmasks the head of her native culture Immortan Joe. He shows benevolence in his gushing gift of life-supporting water to the people. But in reality, he simply holds certain women in a captive maternal state while he enslaves his the native culture. Furiosa must unmask him and then defeat him.

In Hunger Games, Katniss Everdeen, too, must unmask the president of her native culture, President Snow. The unmasking of the minotaur is what leads toward revolution by the native culture.

In Coco, which follows the heroine’s labyrinth model, Miguel must unmask his own idol, Ernesto de la Cruz, as an oppressive minotaur who unfairly rules the underworld and destroyed his family.

In Aladdin, Jasmine must unmask Jafar.

In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy Gale famously unmasks the great and terrifying Wizard of Oz (with a little help from Toto).

In Silence of the Lambs, Clarice Starling must first unmask and then defeat the notorious serial killer, Buffalo Bill.

In Titanic, Rose must unmask and escape the seemingly benevolent, diamond-gifting Cal Hockley.

In Beauty and the Beast, the minotaur turns out to be hometown hunk, Gatson, whom Belle must unmask and defeat.

In Pan’s Labyrinth, the young Ophelia discovers the minotaur in her home environment as well. The minotaur is her own fascist stepfather, who cares only for having a son and nothing for his wife and stepdaughter.

Finally, in Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon, one of my all-time favorite heroine, Shu Lien unmasks the painted aristocrat’s daughter, Jen Yu, as the namesake, “hidden dragon.”

In all these cases and so many more, heroines are unmasking members of their native culture who hide in plain sight. I think this is a unique recurrent theme in the heroine’s labyrinth, in which the heroine models heroic behavior outside the traditional hero’s journey.

A great example of both storytelling models exactly side by side is Wreck-It Ralph. Ralph must leave his native culture to fight distant dragons and become worthy of a medal. Vanellope, though, must unmask King Candy as the sociopathic Turbo, who is the oppressive hidden minotaur within her native culture (or video game).

Most of these examples are in film because films are visual and immediately resonating. What do you think? If you have other examples of heroines unmasking hidden minotaurs, feel free to mention them below. More blogs about heroines will follow.

To learn more about the core concepts of the heroine’s labyrinth, click here

Sep 11, 2019

For the first time in history, we’re getting a glimpse of a heroine-centric world view in our cultural stories. In the long history of humanity, the vast majority of literary storytellers and historians have been men. But I believe there is a historic shift occurring and the art of storytelling, itself, may be changing.

When I sat down to write a novel about Byzantine Empress Theodora, I followed the prevailing model for story structure and character development known as the Hero’s Journey. For decades now, the Hero’s Journey has been one of the most dominant models for storytelling out there and for good reason. It works. However, the Hero’s Journey has been criticized at times for being a little, well, male-centric. I never understood the criticism until recently. While writing my historical fiction novel, which features a strong heroine, I realized that I didn’t understand heroines as much as I thought. At times, I veered away from the Hero’s Journey and found myself following my heroine’s unique journey.

But I needed help.

What I really needed were the insights and perspectives of other women. With a genuine desire to get my lead heroine right, I opened myself up in full, and I listened to the feedback of multiple women beta readers. I knew about Theodora from the history books but I never knew Theodora as a woman. There were small things. For example, some of the most common questions from beta readers were:

“What’s she wearing?”

“What’s she eating?”

I didn’t realize that so many women readers really liked knowing about Theodora’s clothing and delicious Byzantine cuisines. Oddly, answering those simple questions brought Theodora just a little more to life.

But then there were big things. More intense questions were:

“But what about her daughter? You never mention her.”

“Isn’t she nervous in this situation?”

And when Theodora had conversations in certain scenes, the most common question of all: “How does Theodora feel when that person said that? I want to know how she took that.”

I blew by certain moments that the beta readers didn’t. By simply answering the questions thrown at me, I began to see my heroine in ways I never before imagined. I felt as though I was picking up a special frequency that I never paid attention to previously. I dare say that my attitudes toward women in real life also changed. Unexpectedly, I started to see my heroine’s problems in a woman at the grocery store. I wondered “how she felt” during my own conversations. I noticed my heroine’s social frustrations sprouting up even with my wife.

As a writer, I began to recognize the same problems and themes our heroines face in movies and literature. I now watched films with an added focus and a new set of eyes. A pattern emerged that I never noticed before, even when watching movies I’d seen a hundred times. With so many heroines to watch now, from Game of Thrones to Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel, I saw something more pronounced, more vivid, more powerful than mere fictional characters.

A heroine.

Her storyline differs from my boyhood heroes. She faces different threats. She’s brave in different ways, goes to different places, and often solves different problems. And surprisingly, I noticed that our heroines face villains who are not far away but close by—members of her own native culture. She encounters what I have labeled a “cult of deception,” which is a systematic way of being misled or misdirected, even by those she trusts. Unlike my male-oriented heroes, she’s not trying to embrace the cultural traditions of her father’s (or mother’s) past but instead trying to break away from them. The past is the problem.

Folks, these themes are not the Hero’s Journey. When I thought about my lead character, my wife, my mother, my female friends and acquaintances, and now these cultural heroines, I realized that I had changed. Some big questions hit me.

What if the Hero’s Journey is the result of an aggregate world view that has been mostly male up until now. What if the aggregate world view of our heroines is creating a different monomyth? What if the very nature of the conflicts that heroines face, the villains they defeat, and the way they save the world all bear notable distinctions? What if the woman as the cultural figurehead of civilization has powerful messages that society has never experienced before on this scale?

That’s cultural change.

If our stories reflect recurrent themes about the male or female experiences in life, then perhaps stories are a starting point. Maybe we can better hear each other more clearly through our stories.

I’m going to write a series of blogs introducing the principles of heroine-centric storytelling. I hope you’re excited to read and discuss it. To see a brief overview of the core concepts of a heroine-centric story model, click here or you can follow me on Facebook to stay updated.

So, what are your thoughts? Do you think that heroines, in general, might have some distinctive qualities that have gone unrecognized? Do you think there is such a thing as a heroine-centric story structure?